Image revolution of early Soviet cinema still speaks volumes

Vivid colours, deep backgrounds, floating heads. This is Kino/Film, a new show at the Gallery of Russian Art and Design (GRAD) in London which examines the golden age of Soviet film posters - many of them rarely seen before. Kicking off the year of Russian/UK culture, the exhibition offers a unique glimpse into a radical period in the history of both Soviet film making and promotion.

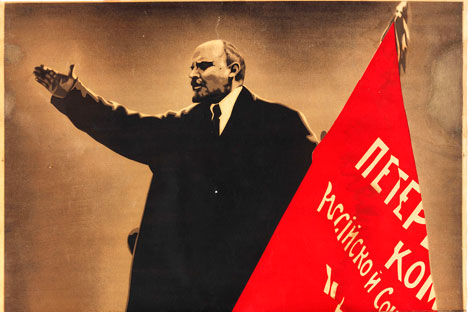

Taking its cue from Lenin’s declaration that film was “the most important art” for promoting socialist values, the 1920s was a phenomenal time for Soviet cinema, both for documentary and features. A relatively new art form, it flourished under the spirit of revolution as young directors embarked on a journey of experimentation.

“It was creativity on an unprecedented scale,” says art historian and film critic Lutz Becker, a curator of the exhibition, adding that films of the 1920s exuded an immense positive energy.

In a society that aimed to transform humankind through industrialisation and technology, film-makers were encouraged to break with conventions and develop new ones. Many notable and popular films appeared during this period, from the iconic works of Sergei Eisenstein (Battleship Potemkin, October) and Vsevolod Pudovkin (The End of St Petersburg, Mother), to pioneering documentaries by Dziga Vertov (Man with a Movie Camera).

These directors introduced radical cinematic techniques such as montage, repetition, asymmetric viewpoints and dramatic camera angles, which set new standards for the newsreel, the feature and the documentary film. Although primarily intended as propaganda, these works transcended their ideological subject and went on to inspire generations of cinematographers outside Russia, and still influence contemporary practice.

Take, for instance, the editing and montage style pioneered by Eistenstein and used so masterfully in his famous Odessa steps massacre scene in Battleship Potemkin (1925). Its powerful emotional and theatrical effects have been widely mirrored in famous scenes in Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho or in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather.

After massacre scene of Battleship Potemkin in Odessa, the steps calls by the film - Potemkin steps. Source: Youtube

Meanwhile, the aesthetic documentary experiments of Vertov gave rise to a cinema verité style of cinematography and inspired such diverse film-makers as Jean-Luc Godard and the French nouvelle vague movement of the 1960s, and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave) in the present day.

First time film director decided to be totally different from theater art. Source: Youtube

Pudovkin was another great pioneer of the montage technique. His best-known work is Mother (1926), which was internationally acclaimed for the radical intensity of its editing techniques, as well as for its emotion and lyricism. Experiments by other notable cinematographers, such as Aleksandr Dovzhenko and Lev Kuleshov, also made their mark on world cinema.

Pudovkin's mother, an example of a movie with emotions, not ideology in the foreground. Source: Youtube

Silent film posters reflected this prevailing spirit of innovation. Across the country, new movies were advertised with the help of radical designs by some of the most talented and creative artists, including the Stenberg brothers, Yakov Ruklevsky, Aleksandr Naumov Nikolai Prusakov and Mikhail Dlugach.

Each artist was unique: the posters of the Stenberg brothers, for example, were reminiscent of their own Constructivist sculptures, while Supermatist designs were a trademark of Prusakov. Many of them had a background not only in art but in architecture, stage design and photography.

These artists created a new ‘visual vocabulary’ by translating practices they saw on screen into print. Experiments with geometry, colour and typography were employed to capture the essence and energy of each cinematic production, creating a distinctive and highly influential body of work.

The exhibition stresses this symbiotic relationship by showing excerpts from some of the films alongside the posters. The ‘cinematic’ playfulness of some of the prints is exhilarating. The Three Million Case for instance was a Soviet comedy based on popular American slapstick movies. Although the film itself has been somewhat forgotten, the poster design, with a head looming above two vignettes in which another character scales a building, is still fresh and vibrant more than 80 years on.

Elena Sudakova, the founding director of GRAD, explains the lasting appeal of these designs, saying: “The dynamism of the images and the juxtaposition of unexpected elements make these posters much fresher and more exciting than most film advertising today.”

Somewhat ironically, this new artistic vocabulary born in the Soviet Union went on to inspire commercial print artists in the United States, as they became aware that modernist graphics would attract the eye of consumers. Elements of Soviet design appeared on packaging and in houseware patterns.

Both posters and films were the aesthetic of Soviet revolution and modernisation. In the hands of Eistenstein or the Stenberg brothers, they became ideological, a mechanism for socialist change. At the same time, they were never conformist or puritanical. They aimed to disorient, thrill and transform.

This is why the ideas of these artists continue to resonate with film-makers and designers working today, and are certain to inspire many more works yet to be made.

In the words of Sudakova: “These works continue to be revisited.”

Kino/Film: Soviet Posters of the Silent Screen, GRAD: Gallery for Russian Arts and Design, 17 January - 29 March 2014 www.grad-london.com

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox