Natalia Nikitina found the recipe for the traditional Kolomna treat in the library archives. Source: Pavel Inzhelevsky, RBTH

In the town of Kolomna, not far from Moscow, Russia’s culinary traditions are being revived. Sweets are made from historic recipes that have been painstakingly recreated while bread is baked the old fashioned way.

Pastila is a traditional Russian sweet, an oven-dried dessert made from whipped berry or apple puree, which was popular in pre-revolutionary Russia. And in the 19th century, there was no better pastila than that from Kolomna. More than one company got rich on the famous treat. But when the Bolsheviks came to power, businesses were expropriated and production was shut down. The taste was forgotten and the recipe lost. “Kolomna lost one of its distinguishing features,” says Natalia Nikitina, director of the Kolomna Museum of Forgotten Flavors. “Now, after nearly a century, we decided to resurrect the process. No one expected that it would be in so much demand. No one thought of doing this.”

Medieval preserves

Natalia found the recipe for the traditional Kolomna treat in the library archives. Together with her friend Elena Dmitrieva, they began to study the historical documents. It turned out that the pastila made in the 15th century was a kind of “Medieval preserve” – after it was dried it could be stored for long periods of time without molding or losing its flavor. Add boiling water and wait a few minutes and you’d have a fruit puree that could be eaten in the heat of summer or during the long winter.

The Russian word pastila comes from the verb postelit’, to lay, as before drying the puree is spread out on paper or a cloth. “Recreating this process in 2008, we tried to place a small order with a number of confectionary companies,” says Nikitina. “We tried seven different factories and were turned down by each one. No business plan, no certificate, no packing, etc. But that didn’t stop us.”

Source:

A cultured treat

Today partners Natalia and Elena manage a bakery, two candy-making facilities, and four museums in Kolomna. Their project has created hundreds of jobs, while the number of tourists visiting Kolomna is up by 250%. Each of the museums welcomes more than 50,000 visitors annually. Most visitors take home a souvenir – a box of Kolomna pastila, jam, herbal tea or a kalach, a traditional type of twisted or braided bread, sometimes baked with a “handle” and made from finely sifted white flour.

Sales support the operation and development of the museums – and Kolomna has a reputation as a very popular tourist centers. But this money isn’t always enough, and the partners have searched for investors, competed for grants from private foundations, and negotiated with the city administration to lease space. “It wasn’t easy, but we didn’t take one ruble of government money and we remain a private organization,” said Nikitina. “Everything we earn, we reinvest.”

A taste for the creative

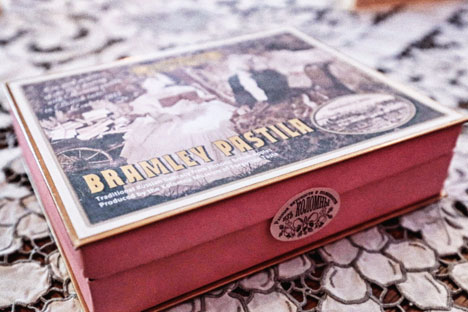

A box with pastila. Source:

In the souvenir shop at the Museum of Forgotten Flavors, there’s considerable choice today. From that first recipe unearthed in the dusty library archive, the range has expanded to 33 flavors. Among the wealth of sweets, there’s a line devoted to Russian writers. For example, we have Leo Tolstoy’s favorite pastila, the recipe for which was found among the papers of his wife, Sophia Andreevna. “Tolstoy’s Pastila” was number 151 in the cookbook she meticulously compiled and intended to publish.

The Kolomna businesswomen reconstructed the recipe together with the State Tolstoy Museum. “In another example, the Darovoye Estate, where Dostoevsky spent 7 years of his childhood, is not far from Kolomna,” says Nikitina. “In his second wife’s letters there is mention of his incredible sweet tooth. He always kept raisins, fruit jellies, chocolate, and honey on hand, and always bought red and white pastila. We’ve made these varieties.”

An experiment in purity

British art historian and Kolomna pastila connoisseur Andrea Rose introduced Nikitina and Dmitrieva to Andrew Jamieson, the owner of an apple orchard in Norfolk and the managing director of Drove Orchards Ltd. Andrew inherited the orchard from his father, who in turn inherited it from his father. However, Natalia and Elena aren’t interested in the family tradition, but rather the variety of apple. Jamieson grows Bramley apples, which are slightly sour and well-suited to making traditional pastila. These apples are also “re-creations,” the fruit of the “historical” apple, and not subjected to hybridization for commercial purposes. “These apples are found only in Nottinghamshire,” explains Andrew. Our orchard is a direct descendent.”

London time

|

Finding a common language with the British grower, the ladies from Kolomna investigated a range of London department stores. It turned out that the sweets sold in Harrods and Selfridges have very few natural ingredients. “The British are so unfamiliar with products that contain no dyes or thickeners that they are amazed by natural flavors,” says Natalia. “So we decided to amaze them. We’re opening a representative office and an outlet.”

A Russian-British joint venture called Kolomna Pastila and Apple Orchards has already been registered, and the future product will be called Bramley Pastila. Nikitina quotes Dostoevsky, “Gardening will save the humankind and correct its failings." This is our message. We want to work with these heritage apples and make people happy. That’s all.”

For more information visit the website of Kolomna pastila.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox