Bringing tribute to the gods of the Soviet Union

The bust of Lenin by sculptor Andreev and sketches to him. Source: Olesya Kurpyaeva / RG

Under the escort of propaganda

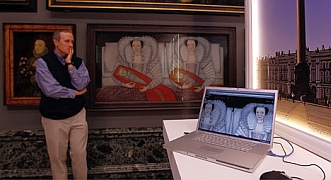

The exhibition has gathered exhibits that have been lying in warehouses for more than 20 years, and many of them had never been exhibited in Russia before. They were shown in Sweden, in Germany, in other countries, but not in Russia. The question is – why?

“There were certain standards for the leaders’ images. Works that did not meet these were rejected at the highest level,” says Lyubov Lushina, historian and one of the creators of the exhibition. “Stalin, for example, had always been depicted with a direct gaze, exuding confidence and peace of mind.” The actual appearance of Stalin – small in stature, with traces of smallpox on his face – did not inspire due reverence.

The real biographies of the leaders were not as heroic as they would have like them to be. That is why many of these items were never displayed in public. The cards with numbers and children’s drawings that Lenin’s wife Krupskaya used to teach him anew to read and count after a stroke… Stalin’s picture of a girl feeding a lamb with a bottle of milk, which he cut out of his favorite magazine Ogonyok... these did not fit the carefully cultivated image of heroism. People were to treat these leaders as icons, avatars of a new religion that the Soviet authorities had invented.

The new religion

The Bolsheviks fought fiercely against the Orthodox faith, seeing in it a competitor. They demolished churches and repressed priests. However, the “holy place is never empty” – as icons and the cross had been outlawed, they had to come up with something new – with Soviet symbols. The five-pointed red star became the new “cross”, while the new “icons” were Lenin and Stalin.

Church Saints were portrayed with a book: A closed book meant sacrament, while an open one meant the path of truth. A poster dedicated to the 70th anniversary of Stalin’s birth portrays him with an open book in his left hand, as Stalin is “the torch of communism”. In this there is a striking similarity to the representation of saints on icons. And among the gifts presented to Stalin there is even a triptych (a portable iconostasis), featuring the six “ages” of the leader.

'Six ages of Joseph Stalin', silver, Georgia. Source: Olesya Kurpyaeva / RG

In the Soviet religion, Lenin was assigned the role of a saint: He was ascribed immortality (“Lenin will live forever”, read a popular slogan), and his remains, stored in the mausoleum on Red Square, were supposed to be imperishable (they were supported by an entire laboratory). Like the saints, Lenin (unlike Stalin) was never portrayed laughing. It was probably for this reason that it was forbidden to show the wooden bust of Lenin depicting him laughing, which can also be seen at the exhibition.

Lenin and Stalin worldwide

Lenin was sent gifts from all over the world, from Japan (a wooden bust of Lenin with prominent cheekbones and narrow eyes in which he is indistinguishable from a Japanese man), from Madagascar (black, with Negroid features), and from Clare Sheridan, the niece of Winston Churchill, who made a bust of the Soviet leader herself. This bust was also banned from public display – Lenin was “too natural”.

There is also the Chukchi legend of the hero Lenin, carved on a walrus tusk, as well as portraits of him made of thousands of grains, of bird feathers, foal wool, poplar fluff, wire, amber, sugar and beads. A prisoner, serving time for forgery, created a portrait composed of texts of Lenin’s quotes. Even a forger respected Lenin. Or maybe there was another reason – he might have been released earlier for such an ideological act.

Stalin received so many gifts that in 1949, on the 70th anniversary of his birth, they were exhibited in three museums. The show featured presents from Italy, France, Germany, and Argentina. There were gorgeous silkscreens sent by Mao (Stalin hung them in the hall of his summer cottage), a leather briefcase made from an entire Brazilian crocodile, and a collection of vintage pipes.

The leather briefcase made from an entire Brazilian crocodile. Source: Olesya Kurpyaeva / RG

By the way, Stalin’s pipe is also a myth. “In his private life, Stalin smoked cigarettes,” says Lushina. “He used the pipe to make the painful pauses during negotiations and meetings. In addition, he looked more imposing with it.”

Stalin himself did not attend the exhibition of his presents – the real Stalin could hardly make an advantageous impression against the background of the fictional Stalin, whose portraits hung on all the walls. However, he encouraged this ideologically adjusted lie about himself.

Once, attending an exhibition dedicated to the 15th anniversary of the Red Army, Stalin stopped in front of a picture in which he was depicted inspecting a cavalry parade in 1919. “Who, if not Stalin, could better know that he was not present at that review,” says Lyubov Lushina. “But, seeing the picture, he smiled and returned to it again and again during the visit.”

Inspiring new generations

“The genius of Lenin will be demanded more than once” and “The current inhabitants of the Kremlin are nothing compared to the great Lenin and Stalin” – many of the comments written by visitors in the guest book at the exhibition demonstrate that even today the myths retain their potency and continue to attract a variety of people.

“We, the new generation of Marxists and Leninists, are grateful to the museum. Your efforts inspire us to continue to perform the covenants of Lenin. Though there are few of us, we have fervent hearts, and our minds crave knowledge,” write some young communists. Thus, Lenin himself was also present at the display. Lenin’s lookalike dropped in after work. He poses for tourists nearby, on Red Square.

The exhibition “The Myth of the Beloved Leader” is being held at the State Historical Museum, 2/3 Revolution Square, Moscow, (until January 13, 2015). An audio guide in foreign languages is available.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox