Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh: London’s holy Russian inspiration

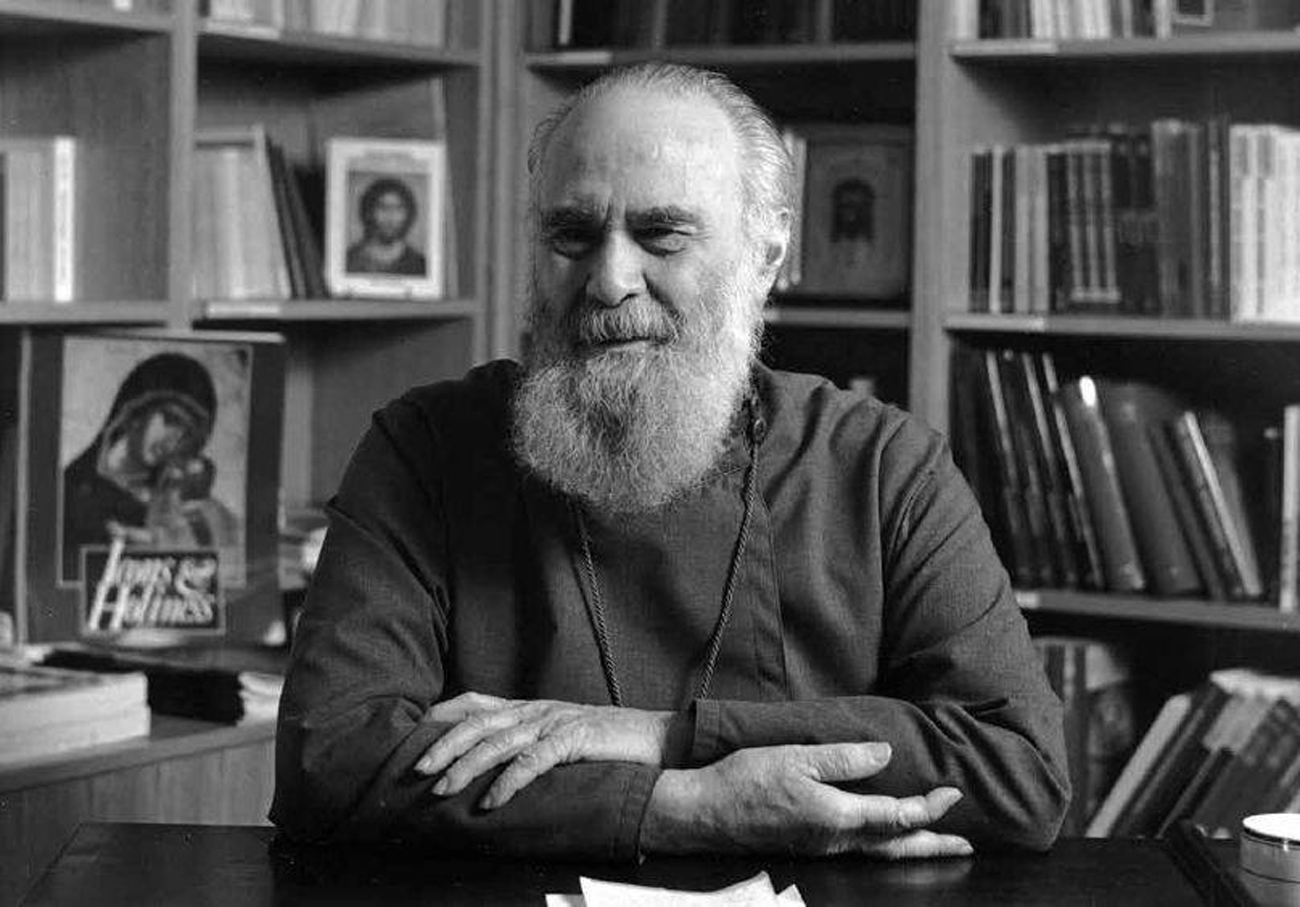

Anthony of Sourozh.

Press PhotoOn Oct. 16 Patriarch Kirill, current head of the Russian Orthodox church, will consecrate London’s newly-renovated Russian cathedral and celebrate 300 years of Russian Orthodoxy in Britain. The brightest chapter in the history of the UK’s Russian churches centers on Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, who started his mission in London in the second half of the 20th century. Charismatic and visionary, he led the powerful congregation-in-exile that grew up around his church in Kensington during the late Soviet era, inspiring not only Russians, but native Londoners too.

A powerful Christian voice

Theological scholar Andrew Walker, writing Metropolitan Anthony’s obituary in the Independent in 2003, called him the “most influential voice of the Orthodox tradition in the British Isles.” Gerald Priestland, a former BBC religious correspondent, went further still, once calling him: “the single most powerful Christian voice in the land.”

Born Andrei Borisovich Bloom in Switzerland in 1914, he studied science and medicine in Paris, worked as a surgeon in the French army and secretly became a monk in 1943, taking the name Anthony. His father was an imperial Russian diplomat; his uncle was composer Alexander Scriabin. Ordained in Paris in 1948, it was as vicar of London’s Russian Orthodox Parish throughout the second half of the twentieth century that Anthony is best remembered. The “Diocese of Sourozh” has traditionally united the British parishes of the Moscow Patriarchate; Anthony became Archbishop of Sourozh (and Head of the UK’s Russian Orthodox Church) in 1962, and Metropolitan of Sourozh four years later.

Hundreds of English converts

Cambridge lecturer Irina Kirillova, who was born in London, remembers Anthony arriving in London as a newly ordained priest; she describes him as part of a generation of emigrants with a mission to preserve their faith and culture and “repay it as a gift to the receiving country”. Walker describes Anthony’s “striking dark looks, and beautifully spoken English - reprised through a French rather than a Russian accent”. Speaking without notes, his ability to captivate his congregations was legendary.

In one of his talks, Anthony reminisces about a courier who happened to be delivering a parcel to the church. The man was an atheist, but as he sat waiting at the back of the church he became aware (as he later explained to Anthony) of “a density of silence he had never perceived in his life”. Watching the people, he said he saw them changed during the service and two years later was baptised into the church.According to Walker, Metropolitan Anthony “attracted hundreds of English converts over the years”. One of those converts was Geraldine Fagan, author of a book about post-Soviet religious policy, Believing in Russia (Routledge, 2012), who describes Anthony as a major influence. “I only met him once in person,” she told RBTH, “but his lectures and writing certainly played a part in my becoming Orthodox.” Fagan describes Anthony as “greatly responsible for the Russian Orthodox Church having any presence in Britain at all” and agrees that: “many people who became Orthodox in the UK did so precisely because of him”.

Keeping faith alive

In 1970 Anthony took part, on BBC radio, in a characteristically witty and forthright conversation with atheist Marghanita Laski. A transcript of this respectful encounter turns up in Anthony’s book God And Man, one of several books about prayer. Jim Forest of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship also talks about Metropolitan Anthony’s vital role in “keeping the faith alive in Russia through countless BBC World Service broadcasts” during the officially-atheist Soviet era. He managed to stay loyal to the Moscow Patriarchate while remaining politically independent, putting him in an unusual position among Soviet Russians. According to one parishioner, Anthony’s recordings were “a lifeline for all the secret Orthodox believers in the USSR.”

Anthony of Sourozh's funerary monument, Brompton Cemetery, London. Source: Edwardx / wikipedia.org Anthony of Sourozh's funerary monument, Brompton Cemetery, London. Source: Edwardx / wikipedia.org |

There were paradoxes in the life of Metropolitan Anthony: theologically conservative, he questioned such fundamental tenets of Orthodoxy as the exclusively male priesthood. Walker calls him “an inspired visionary”, but admits he had “a poor grasp of administrative detail.” Anthony combined a controlling force of personality with a desire to extend participation in the church. He loved to quote Nietzsche's aphorism: “one must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star”, and Walker comments that the phrase “could stand as a summary of his own life.”

Metropolitan Anthony died in 2003 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery, an atmospheric corner of London that is part neoclassical mausoleum, part overgrown, rural churchyard. His grave is near the colonnaded necropolis, currently marked by a black orthodox cross and always surrounded by flowers; Patriarch Kirill is due to bless a new gravestone there this weekend. An international London conference in Anthony's memory this November has taken its title “The Eye of the Storm” from his work. “We are part of a fallen world,” he wrote; “and it is in and through this turmoil that we must find our way … we meet Christ at the very centre of the storm, the point of equipoise of all its violence.”

The Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh Foundation collects and publishes Metropolitan Anthony’s writing. There is information about him and the full texts of his sermons at www.mitras.ru.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox