The untold story: Why Stalin created a cult of Alexander Pushkin

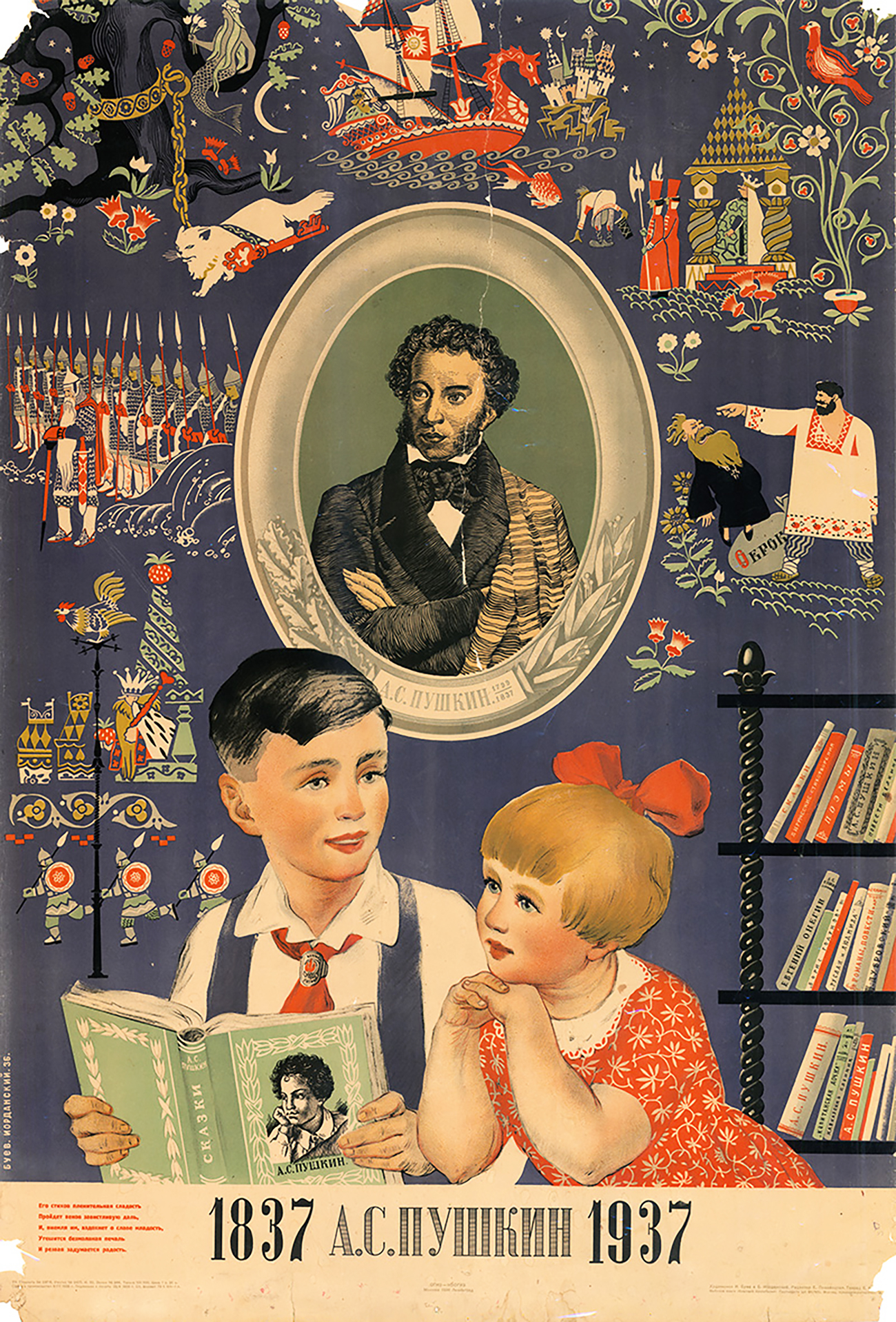

The 100th anniversary of Pushkin's death, Moscow, 1937.

Archive Photo The 100th anniversary of Pushkin's death, Moscow, 1937. Source: Archive Photo

The 100th anniversary of Pushkin's death, Moscow, 1937. Source: Archive Photo

A Soviet god

This year we mark not only the 100th anniversary of the 1917 Revolution, but also the 80th anniversary of the Great Terror in 1937. That year Soviet Russia also commemorated, on an unprecedented scale, the 100th anniversary of Alexander Pushkin’s death. The great poet had hitherto remained in the shadows, but in 1937 he took a central place in the Soviet cultural pantheon.

In place of nationless Marxism that rejected culture, national spirit, traditional statehood, and spirituality, Stalin decided to present the world with an almost classical culture-centric empire that had Pushkin at its heart.

Snatching Pushkin from émigré circles

The decision to celebrate Pushkin as a socialist god belonged to Stalin. To fully appreciate how unconventional his initiative was, it’s worth remembering that in the 19th century Pushkin was a poet known by only the intellectual elite. The reading list for the revolutionary intelligentsia did not include Pushkin because he was considered too distant and removed from the urgent needs of the people.

Stalin, however, was well-versed in classical Russian literature and was fond not only of the revolutionary Chernyshevsky, but also of Dostoevsky and Pushkin.

The decision to celebrate Pushkin was strongly influenced by the fact that starting from the mid-1920s the Russian diaspora abroad, which Soviet Russia was closely watching, developed a strong interest in Pushkin’s works. Stalin himself subscribed to nearly all major publications by Russian émigré circles.

In 1937, the Russian émigré community was planning to hold their own events celebrating Pushkin, which meant that the poet’s legacy could become a dangerous political weapon in their hands. So it was imperative to snatch this tool from the hands of the enemy! Such may have been Stalin’s logic, though historians aren’t sure.

Personality cult

Starting in 1922, annual official memorial services marked the anniversary of Pushkin's death where he was described as a "Russian spring, Russian morning, Russian Adam," and also compared to Dante, Petrarch, Shakespeare, Schiller, and Goethe.

Pushkin’s cult was promoted on an unprecedented level. Preparations for the anniversary involved everyone - academics, writers, composers, politicians and public figures, publishing houses, cinema companies, theaters, factories, as well as collective and state farms. Every single person in the country was to know that Pushkin is great! Pushkin is sacred!

New monuments to Pushkin were unveiled in Leningrad, Kiev, Minsk, Tbilisi, and Yerevan. New streets, squares, schools, parks, subway stations, train stations, collective and state farms were either renamed after Pushkin or built in his honor. Artists painted giant canvases dedicated to Pushkin, composers wrote music singing his praises, and the leading theaters of Moscow and Leningrad competed in a race to make productions of Pushkin’s works.

Stamps from the series "Alexander Pushkin's Death Centenary." Designed by artist Vasily Zavyalov. Source: Alexey Bushkin

Stamps from the series "Alexander Pushkin's Death Centenary." Designed by artist Vasily Zavyalov. Source: Alexey Bushkin

Pushkin’s name was exclaimed by loudspeakers and gramophones, streets and squares were decorated with his portraits, and posters and postcards were printed. Literally every school, factory, and collective farm throughout the country staged nearly identical exhibitions about Pushkin.

Hordes of fans

The total number of anniversary Pushkin publications exceeded 14 million copies. They were published in practically all languages spoken in the Soviet Union, including Assyrian, Buryat, Greek, Hebrew, Komi-Zyryan and many others.

Factories and collective farms suddenly saw hordes of enthusiastic fans and connoisseurs of the poet’s works, and clubs of Pushkin lovers were formed. Artistic associations and master craftsmen, just like the icon painters of the past who created images of St. Nicholas for the people, flooded the country with hundreds of thousands of Pushkin statues, busts, and other visual reminders of his life.

Soviet poster marking the 100th anniversary of Pushkin's death, 1937. Source: Archive Photo

Soviet poster marking the 100th anniversary of Pushkin's death, 1937. Source: Archive Photo

On Feb. 10, 1937, the very day of the anniversary, an official gathering was held at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow to mark the centenary of the death of Russia’s greatest poet. The entire Communist Party elite, including Stalin, were present.

The event was broadcast to the nation, and at the opening Andrei Bubnov, the People's Commissar of Education and Chairman of the Pushkin Committee, exclaimed: "Pushkin is ours! It is only in a country of socialist culture that the name of the immortal genius is surrounded with ardent love; it is only in our country that Pushkin’s works have become a treasure for all the people.”

The glorification of Pushkin was complete, and the poet’s cult established. In the words of the philosopher Antonio Gramsci, the cult of Pushkin "cemented the popular forces," uniting a multi-ethnic country in a common cultural space and thus becoming a most powerful imperial unifying force.

This is an abridged version of the original article published in Russian at Vzglyad.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox