What’s behind the Kennan Moscow Office closure?

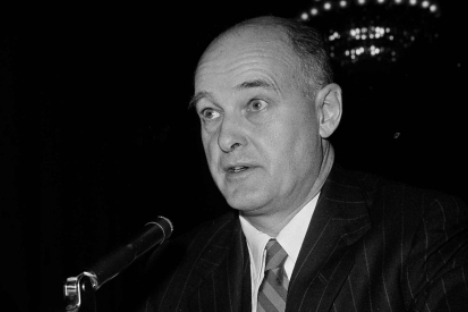

George F. Kennan, former ambassador to Moscow, was one of the founders of the Wilson Center's Kennan Institute. Source: AP

Following the news of the Wilson Center’s decision to close the Kennan Institute’s Moscow office, Russian commentators have argued that this move may affect long-term academic collaboration between Russia and the United States. Meanwhile, a number of think tanks have expressed their regret at the loss of such reliable partners.

The news about the Wilson Center’s plans was revealed by Kennan Institute's fellow Victoria Zhuravleva, who is also a professor of American History and International Relations in the Department of International and Area Studies at the Russian State University for the Humanities. She is one of the initiators of the open letter from the Kennan Institute’s alumni in Moscow that was posted on Feb. 10.

Earlier, Matthew Rojansky, director of the Kennan Institute, told Voice of America that he does not intend to close the center, but rather reduce and reorganize its presence in Moscow because of lack of funding from private donors and one of the U.S. federal programs such as Title VIII.

Russian academics protest Kennan closure

The Russian academic community reacted with shock and alarm to the recent decision by the Washington, D.C.-based Woodrow Wilson Center to shut down the Moscow office of the Kennan Institute.

“I can absolutely confirm that Kennan is not disappearing from Moscow or Russia,” Rojansky told Russia Direct by e-mail.

“We remain 100 percent committed to working with our over 400 alumni in the Russian Federation, offering fellowship opportunities, promoting exchange with U.S. scholars, co-organizing conferences and meetings, and publishing and disseminating scholarly work — in short, the key areas of Kennan’s work in Russia for over 20 years. The financial challenge we have faced is very real, and as a result we will simply have to find more financially sustainable ways to do this work. We are engaged in that task right now, and will announce our future plans very soon.”

Likewise, Zhuravleva is concerned with the situation. “The Moscow office is going to be closed and the funding may be stopped,” Zhuravleva said. According to her, it remains unclear in what format the Kennan Moscow Project will work in the future.

The launch of the Moscow Kennan office 21 years ago brought together a generation of Russian and American experts studying Russia and bilateral relations between the countries.

“The situation is very weird,” Zhuravleva told Russia Direct. “Although the office passed inspection by Russia’s authorities, it is Washington that closed it in the wake of the decline in U.S.-Russia relations.”

Russian alumni of the Institute has already sent the letter to U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, and has also posted it on social media.

According to General Director of Russian International Affairs Council (RIAC) Andrei Kortunov, the closure of the Moscow office is in line with the trend of halting U.S. supporting activity in Russia.

“For many, it will be bad news that indicates that America is losing interest in Russia and switching to other regions,” he said pointing to the 2012 closure of the U.S. Agency of International Development (USAID).

Indeed, Washington seems to be disengaging from Russia. Last year, U.S. Congress announced plans to withdraw funding from the Title VIII Grant Program, which supports regional studies related to Russia, Eastern Europe and the states of the former Soviet Union. The program supports U.S. citizens in pursuing language training and policy-relevant research in the social sciences and humanities.

“In 2002 the program’s budget was $4.5 million ($5.8 million in 2012 dollars), but it was cut to $3.3 million in 2012 and to $0 in 2013,” wrote Laura Adams, director of the Program on Central Asia and the Caucasus at Harvard University, in her column for Russia Direct.

Zhuravleva argues that despite the recent cuts in funding U.S. programs related to Russia and The Wilson Center’s serious financial challenges, it seems to be a reckless decision to close the Kennan Moscow office in the year when it is celebrating its 40th anniversary and 21 years of activity in Russia.

“[Given the fact] that Kennan Institute is one of the leading U.S. center in Russian Studies, it [the decision] will affect U.S.-Russia relations,” Zhuravleva said. “After all, the Kennan Institute has always called for a non-governmental dialogue between two countries.”

Can the Kennan Office closure affect the U.S.-Russia relations? Read more experts’ opinions in the full version of the story at Russia Direct.

Russia Direct is international analytical media outlet with the focus on foreign policy. Its premium services, such as monthly analytical memos and quarterly white papers, are free but available for subscribers only. For more information about the subscription, please visit russia-direct.org/subscribe.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox