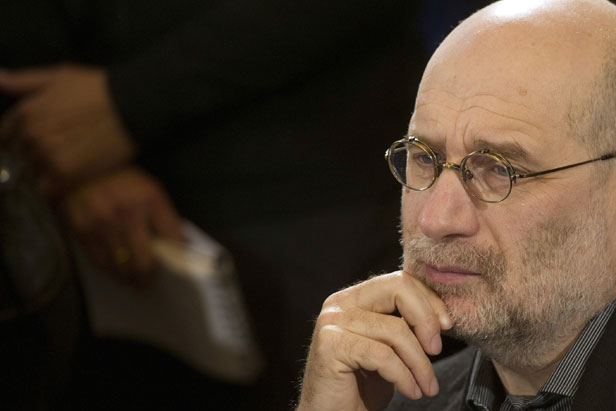

Boris Akunin, famous Russian detective writer, tranlslator and publicist, decided to write a history of Russian State. Source: RIA Novosti

You can’t help but envy Boris Akunin, whose tsarist-era detective novels delight Western readers as well as Russians. He’s incredibly prolific and ten of his novels have been translated to great acclaim.

Novaya Gazeta: What’s your goal with this monumental project?

Boris Akunin: I hope to paint a picture of Russia’s history, one that has a certain kind of architecture but is not bogged down in this or that theory. Secondly, I want to instill my love for history in everyone. And finally I’d like to change the genre of literature [I’m working in] to write something different, and about something different. Three goals are enough, I think.

N.G.: What exactly are you planning to look at in your work?

B.A.: The

history of the Russian State. That is, the political history, and the history

of the continuity of governmental institutions. I’ll touch on different spheres

of life – economics, religion and culture – only in as much as they are

connected with the history of the state itself.

N.G.: Are you going to discuss existing concepts on the history of the Russian State? Which historians do you trust, for example?

B.A.: I’ll mention them in passing, but I’m not going to go into any depth. When I set to work on the project I told myself that I couldn’t bring any prejudices with me. All theories and concepts are welcome.

The degree to which I trust any given author depends on whether I get the impression that the work had been ‘ordered’ by the government, or how much polemical quagmire I have to wade through. The greater the polemics, the less I trust the author. My own style is not controversial or polemical. And I’m not trying to make any new discoveries or ‘say something new.’ I think that historians will hardly find my work interesting.

In Soviet times, the genre got the rather ugly title of ‘Scipop.’ My “History of the Russian State” will be a systematic description of facts that people already know, written in plain language.

N.G.: Do you have your own opinion about the history of the Russian State?

B.A.: Of course I do, but it doesn’t differ greatly from those that already exist. And, naturally, I draw my own conclusions as well. But I usually put them at the end of each section (and volume), when the reader has already been exposed to all the facts and we’re on a level playing field. This way, the reader is free to come to his own conclusions, which may be different from mine.

N.G.: What should readers believe your account of history, rather than anybody else’s?

B.A.: I

hope that my frankness will appeal to them; I’ll often write, “I’m not sure

about this, but in general nobody knows for sure.” It doesn’t really matter if

the reader doesn’t agree – in fact, that’s a good thing. The main thing is that

they are interested in history. As part of this project, I want the best books

on this particular historical period to be released at the same time as the

next volume in my series (there’ll be eight in all).

N.G.: How is your research going? What stage are you at right now?

B.A.: The first volume, which deals with the period of Kievan Rus’ [9th to 12th century] up to the Mongol invasion, is already finished. Now it’s being prepared for publication – the illustrations and maps are in production, and experts have been engaged to check facts and details. At the same time, I’m writing a short story about Kievan Rus’; there’ll be three of them in the first volume. We’re going to have this kind of alternation of styles – fact to fiction and back again – it makes the work come to life and gives it some variety.

N.G.: Why do you think the work is so easy for you?

B.A.: Because I don’t view it as work. For me, delving into the history of my native country is not work at all – it’s a pleasure. I lose myself in the material, because it’s so interesting. I separate the information into four parts, or strands of hair, if you will: the facts, the hypotheses, amusing details and my own thoughts. Then I plait the hair and we get a beautiful braid. It heartens me to think that I’ve found a wonderful pastime for the next 10 years or so.

N.G.: We

don’t know what life will be like in 10 years. But, if we are to believe what

Putin has been saying about history, then it seems that we’re heading for a

complete revision of Russian history as it is taught in schools. That is, our

children will learn that there is one ‘single and true’ history. Can it be that

simple?

B.A.: There are two main genres of historical works. The first is generally accepted facts. This is what should be taught in schools, for example. Then there are interpretive accounts of history – research, new theories and hypotheses. It stands to reason that the first category should be more consistent. But we should try to avoid categorizing. That’s the kind of ‘history’ that I write—beyond categories.

First published in Russian in Novaya Gazeta.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox