Russian soul in search for God

|

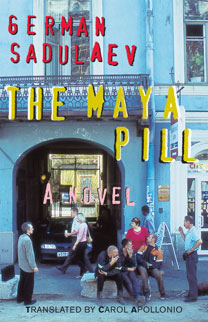

| 'The Maya Pill' by German Sadulaev. Dalkey Archive Press, 2014 |

Editor's note:

German Sadulaev’s novel “The Maya Pill” is a biting contemporary satire focused on a classical Russian theme of a modest individual’s quest for his spiritual identity. But it’s approached in a twenty-first century bizarre style, when Sadulaev’s protagonist comes across a medicine that seems to make everyone happy – but is this the right way? A short excerpt from the novel presents the author’s unusual view on the “mystery of Russian soul”.

Maximus took a shower, boiled himself four eggs for breakfast (lunch?), and decided to take a drive. Somewhere, anywhere. One of his magazines had an article in it about an archaeological site, a three- or four-hour drive away. Though of course he had to figure out where he’d left the car.

Maximus dressed, went out, and hailed a taxi heading downtown. He found the car right where he had left it the night before, near the Tribunal. Untouched by thieves, hooligans, or the tow truck. A good omen. And Semipyatnitsky headed north.

<…>

It’s only on the map that we’re one big united country, all one color. But the land isn’t a map, it’s forests and rivers, fields and ravines. And for one place to be united with another, you need a road.

Centuries ago people on the flatlands settled along rivers, mostly because the rivers served as highways linking one world to another. You can’t get far traveling through the great slumbering forest or across the vast empty steppe, especially if you’re hauling goods for trade. The Varangians, those bandits and traders who founded the Russian state, had traveled by river, if you buy that theory about the Norse origins of Rus, that is.

Semipyatnitsky had no intention of going all the way to Murmansk. His destination was the village of Staraya Ladoga, Russia’s first capital, the place where the Varangians had begun their expansion onto the Central European highlands. He wanted to see that landscape for himself, to feel what those energetic Norse adventurers had felt so long ago. To unwind the scroll of the country’s history back to zero. To understand how and why things had turned out the way they had. The road was long. Nothing on either side. Semipyatnitsky recalled a phrase from a guidebook for tourists: “Some ten percent of Russian territory is densely populated; twenty percent is relatively civilized, and seventy percent is virgin land.” Tselina, in Russian. The land is a young girl. A virgin, you say? But what if she’s an embittered widow, an old trollop?

What do we need all this space for? For nothing—all that emptiness just gets in the way. We cross it in haste and in shame as we travel from one oasis to another in our busy lives. Indeed, if Moscow were closer to St. Petersburg, and Rostov-on-Don to Moscow, with Novosibirsk nearby, it would be a lot easier to govern and supply. You can see why the tsar unloaded Alaska in exchange for a couple of glass beads: He knew that the cord binding it to Russia would unravel.

Yes, in the big cities people fight to the death for every square meter; the buildings cram in closer and closer together and rise higher and higher, grasping at the last remaining breathable air, reaching up to the heavens. Along Russia’s horizontal axis, however, the only things that grow and multiply are cemeteries and wasteland: pustosh. You could cover four or five cities with the palm of your hand, and all the rest of Russia is one giant empty wasteland.

And it’s all the same: above and below, outside and inside. Above the scorched, burned-out land is an empty sky, devoid of color. And inside your heart too: nothing there, just parched, wretched emptiness: pustota.

Wasteland, pustosh. The word entered Semipyatnitsky’s head and surrounded itself with other thoughts. An ancient word, conveying an exact meaning: pustosh, wasteland, not pustota, emptiness. Emptiness entails something Buddhist, a vacuum, there is something postmodern and pretensions about it. But pustosh is primordial. Like a pagan divinity: Mokosh . . . Pustosh . . . God of Emptiness.

Emptiness, though, pustota . . . is just emptiness. It is and always has been, from the beginning. And will remain so, permanently. Emptiness is cold, no way out. Wise: Chinese, Hindu. Eternal, indifferent.

Whereas pustosh is warm and melancholy. It contains the past, what’s gone by. In what is now pustosh, grain used to be harvested, great households stood, gardens and lush orchards grew and flourished. Then everything burned to the ground. Weeds grew tall and covered the arid soil. It’s abandoned now: no one there, just an old wino digging a hole in the earth. Planting sunflowers, maybe, on a whim, or digging a grave for his dead dog.

Then there’s pustinya, desert. That’s different too. Pustinya is sand, wind, a white camel, the Prophet on her back—peace be unto Him—she’s taking him from Mecca to Medina, or is it from Medina to Mecca, whatever, bearing Him on her back, and along with Him, salvation to all mankind.

Maybe it’s a bad thing that the land is so empty, but emptiness is necessary, because emptiness is a space that can be filled. Though everyone’s emptiness is different.

For the Chinese, the entire world is emptiness, pustota. Sewing Dolce and Gabbana labels onto trousers in some basement sweatshop, stealing the design for a concept car from Toyota—nothing is sacred. It’s all emptiness, and emptiness is Tao. Emptiness is the inner essence of things. And any form is simply a label pasted on emptiness, predetermining the way our untrustworthy senses will perceive it. So what’s the point of copyright, of defending someone’s asinine trademarks?

For the Arab, the whole world is a desert. Pustinya. And he couldn’t give a damn that there are other people living on the globe who’ve built great cities and roads, who have something that they consider to be civilization and culture. No, they’re all savages, heathens. The Arab rides alone in all his glory, regal and handsome on that white camel, a sack of petrodollars in one hand and an Kalashnikov automatic in the other, bearing either the Prophet’s teachings—peace be unto him—or salvation through death, take your choice, O infidels who wander in the darkness.

Whereas your European hates emptiness in whatever form. He covers it with construction projects, divides it into plots, parcels them out, maps everything, and presto, no more emptiness! Or so it seems. But no, it’s emptiness nonetheless: pustota.

For a Russian, though, wherever you make your home is wasteland. Pustosh is the Russian natural landscape. And any other terrain a Russian finds beneath his feet inevitably turns into that same wasteland which is so dear to his heart. Even his apartment becomes pustosh.

Because when you find yourself in a wasteland, it’s only natural that your thoughts turn to the futility of life.

There they are, the remains of empires, the bygone glory of kingdoms, and what now? Futility. From wasteland we emerged, into wasteland we shall return, empty on the inside, on the outside empty too.

At that point it might seem fitting to try and free yourself from the trammels of the material world, but such a quest requires emptiness, pustota. Sitting on pustosh, though, you think: What are all paths? Many have trod and fallen, many have plummeted into the abyss. That too, futility!

But “even if I do not fall into the abyss, the poison will still find me,” sings the bard.* And pours the poison into the glass himself. It is all one path, all Tao, and this glass is Tao, Russian style. He drinks. And imagines himself wandering on roads paved with diamonds, then plummeting into the black abyss . . .

They say that this is Russia’s unique path. The Russian path to God. Through wasteland . . .

And so it is. For any road leads to God.

Maximus recalled something he’d read in Blavatsky or Roerich, a verse they claimed was translated from the Upanishads or something like that: All mountain roads lead to God, who lives on the mountain tops . . .

The Romans thought that all roads led to Rome . . .

And the Bhaktivedanta Swami used to tell his disciples that if they got on the train to Calcutta, they would never reach Bombay.

Funny, and true. But perhaps there is another truth: Any road leads to God.

Though it has two ends.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox