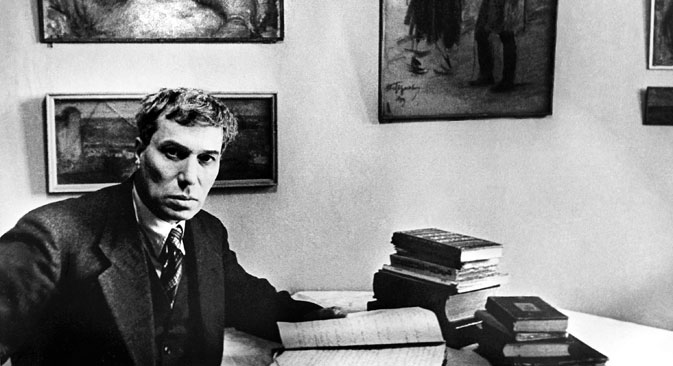

After Soviet censors refused to allow the novel to be published, Pasternak sent a few copies to friends in Europe. It first appeared in Italian. Source: ITAR-TASS

In 1956, following decades of work, the well-known Russian poet Boris Pasternak finished his foremost novel. An epic tale of individual love and suffering, “Doctor Zhivago” was at odds with the officially approved aesthetic, which championed heroic workers and upbeat ideological messages. The Soviet authorities refused to publish it, but the manuscript was smuggled out to Italy. Eventually, it ended up in the hands of the CIA. It was they who printed the first Russian edition of the novel and distributed it at the Brussels World Fair in 1958.

The fair was a rare event that a large number of ordinary Soviet citizens had the opportunity to attend – Belgium issued about 15,000 visas to visitors from the USSR. This was an excellent chance for the CIA to distribute the freshly printed novel.

“This book has great propaganda value,” a CIA memo to branch chiefs of the agency’s Soviet Russia Division stated, “not only for its intrinsic message and thought-provoking nature, but also for the circumstances of its publication: we have the opportunity to make Soviet citizens wonder what is wrong with their government, when a fine literary work by the man acknowledged to be the greatest living Russian writer is not even available in his own country.”

The 1958 edition was only the first one. The following year, the CIA went on to publish a miniature paperback edition – attributed to a fictitious publisher – to be distributed to Soviet and Eastern European students at the 1959 World Festival of Youth and Students for Peace and Friendship, which was to be held in Vienna.

Rumor proved true

|

| The Zhivago Affair by Petra Couvée, Peter Finn, Pantheon, 2014 |

This remarkable fact of the CIA's involvement in the first Russian-language publication of the Pasternak's famous novel is at the heart of Petra Couvée and Peter Finn’s new book, “The Zhivago Affair”, published recently by Pantheon. “The back story of the novel, from its origins to the Nobel Prize controversy, was worth telling on its own,” says Couvée, a lecturer at St. Petersburg State University, but the plot thickened as she began to break through the layers of secrecy surrounding its publication.

Couvée uncovered the part played by the Dutch intelligence service (BVD) back in the 1990s, when a former intelligence officer told her that the BVD helped get the novel printed in Holland in Russian at the request of the CIA. “My first article was a reconstruction of the events, based on Dutch, Belgian, French, Russian, German and American material,” says Couvée. It was published in July 1998 in an Amsterdam literary journal with a “somewhat unresolved ending” and led to a popular TV documentary in January 1999.

Among the viewers were two more retired BVD agents who had been involved in the Zhivago operation. One of them, Kees van den Heuvel, was willing to talk. “I visited him several times,” says Couvée. “He was a wonderful man, young for his 80 years, lively, charismatic. He told me the CIA was the main initiator and driver in the Zhivago project. This was the first concrete evidence of CIA involvement in the Zhivago affair.”

Peter Finn, currently National Security editor and a former Moscow bureau chief at the Washington Post, wrote about this story in 2007 and first approached the CIA two years later, asking to see the agency’s “Zhivago papers.” Permission was refused. “The first response I got … was a flat no,” says Finn; “But of course as a reporter I never take no for an answer.”

“Peter spoke to a number of retired officers,” Couvée continues. “They brought the subject to the attention of the Historical Records Division, and the agency historians in that section became interested.” Finally, three years after Finn’s initial request, the authors got the documents they were waiting for. CIA involvement in the 1958 edition had been “rumored and speculated on almost from the moment the book appeared,” Finn explained, but only now has the agency “finally acknowledged its role.”

Dazzling moments

Couvée and Finn both describe the arrival of the CIA documents in August 2012 as “the best moment.” “They were sent by regular mail to Peter’s home address in Virginia,” says Couvée. The following month, the authors met in Milan to interview the son of Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, the pioneering Italian publisher who produced a 1957 Italian edition of “Doctor Zhivago.” Couvée recalls: “That’s when Peter gave me the documents. It was a beautiful day, so I sat in a small park, the pack of paper in front of me on a picnic table ... It dazzled me. I had started my research in 1997. Was this going to be the grand finale?”

“I instantly knew that the CIA was deeply involved in the printing of the first Russian Doctor Zhivago,” says Couvée. The documents were redacted, but the authors were able to “tease out the names” and flesh out the characters from archives and interviews. Another “thrilling moment,” according to Finn, was holding the actual manuscript, smuggled out for Feltrinelli: “The pages were held together with twine, and it was marked up by Pasternak’s hand,” he recalls.

“The Zhivago Affair” opens in May 1956 with this smuggler, an Italian journalist called Sergio D’Angelo, heading for the dacha village of Peredelkino to persuade Pasternak to give him the manuscript of “Doctor Zhivago.” The authors met and interviewed D’Angelo, who has written his own book about “The Pasternak Case.” “We stayed in touch by email since then,” says Couvée of D’Angelo. “He was, as he always is, incredibly charming and after the interview took us to a local restaurant where we had porcini and boar.”

Mysteries yet to be resolved

The personal encounters with survivors from Pasternak’s circle give the book its vivid, first-hand feel. Although the events it describes took place more than half a century ago, the action is often as full of suspense as a spy thriller. Due to reorganization within the CIA, the documents were not released to the public until earlier this year, allowing Couvée and Finn exclusive access to the material while they worked on the book.

The documents also show

the involvement of British security forces. An unnamed intelligence officer

managed to photograph the manuscript on Doctor Zhivago and pass it to the CIA.

There are one or two mysteries still to be resolved, says Finn: “One of the

outstanding issues … is the name of the original source who gave the manuscript

to British intelligence.”

For Finn: “there were all kinds of discoveries big

and small along the way, from a fragment in a memoir or a piece of

correspondence to a memo from the consul in Munich to the State Department

about a conversation with one of the people involved in the translation of

Doctor Zhivago.” From Couvée’s first discoveries back in the late twentieth

century to this year’s compelling publication, the authors have relished this

literary adventure. “It has always been

a fascinating journey,” says Finn.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox