Rosamund Bartlett. Source: Press photo

Russia Beyond the Headlines: What is your academic background?

Rosamund Bartlett: I wrote my doctoral thesis in Oxford on the influence of Wagner on Russian culture, so I thought I was going to have a career writing about opera and the history of Russian music. In fact I am still intending to write a book about the history of opera in Russia, but I’ve taken a rather long diversion to write biographies of Chekhov and Tolstoy, and translate their prose.

RBTH: How did you come to move from music to translation and biography?

|

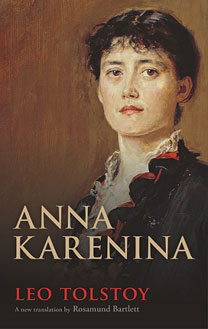

| 'Anna Karenina,' translated by Rosamund Bartlett. Published in the UK in August, will be released in the U.S. on Nov. 15. Source: Amazon.com |

R.B: It was my good fortune to be invited to write a biography of Chekhov and translate “Anna Karenina,” which are once-in-a-lifetime opportunities that I could not turn down. The commission to complete new translations of some of Chekhov’s stories came first, with a view to marking the 100th anniversary of his death in 2004.

I have done research into the apparently musical form of some of Chekhov’s most lyrical stories, in connection with Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich, both of whom saw innately musical qualities in his writing, and this has governed my approach to translation. And the intense experience of translating Chekhov in turn governed my approach to writing his biography. Both activities proved to be mutually beneficial. So I was delighted when I was given the chance to complete a new translation of “Anna Karenina,” having already decided I wanted to tackle a biography of Tolstoy next.

RBTH: Tell us more about how translation has informed your approach to biography and vice versa

R.B: We have this conception of Chekhov as someone who was usually quite closed when it came to personal relationships. What I discovered when translating his stories, however, is that he is very open, by contrast, when he writes about nature, and particularly the steppe landscape that lay beyond Taganrog, the southern provincial town where he grew up. It remained his chief source of lyrical inspiration, and naturally became the subject of his first story for a serious literary journal. Rather than taking a standard life-to-death approach, therefore, I decided it would be more revealing to structure my biography of Chekhov through his relationship with place: the stifling merchant environment of Taganrog, the more stimulating one of Moscow where he worked as both doctor and writer, the astounding journey he took across Siberia to conduct a census of the penal colony on Sakhalin island – and many more. With Tolstoy, it was the other way around, as the deeper understanding I gained of his personality through writing his biography made me more sensitive to the idiosyncrasies of his literary style when translating his prose.

RBTH: Have you been to all of the places associated with Chekhov and Tolstoy in Russia?

R.B: I have been to most of the places where Chekhov lived, such as Taganrog, Moscow, Melikhovo, Yalta and Nice. But I have yet to visit Sakhalin and Sri Lanka, where he stopped off on his journey home from Siberia. Where Tolstoy is concerned, naturally I’ve made several trips to Yasnaya Polyana, where he spent some 70 of his 82 years, and have also visited the more remote railway station at Astapovo, where he died. Last year I was excited to travel to Optina Pustyn monastery, a famous place of pilgrimage for 19th-century Russian writers, including Tolstoy, who went to consult its famous elders. One day I hope to set eyes on the steppe landscape beyond Samara, where Tolstoy liked to spend his summers.

RBTH: How long did it take you to translate “Anna Karenina”?

R.B.: It’s difficult to say exactly, as I stopped work after completing a draft of the first half of the novel in order to write my biography of Tolstoy, then resumed again.

But it’s probably the work of about three years in total, maybe more. When I got to the end of my first draft and started to revise, I found I was incredibly dissatisfied with how I had translated the earlier chapters, which perhaps indicates that I had begun to understand the novel better. No doubt I would have gone on revising forever if I hadn’t had a deadline.

RBTH: What difficulties have you faced in translating Russian literature?

R.B.: For some reason I don’t find Chekhov too hard to translate, although it’s difficult to reproduce his extraordinary concision in English. He packs an awful lot into very few words. Tolstoy is generally very difficult to translate, although he is probably the easiest writer to read. He is incredibly challenging, because he writes in such a clear and natural way, using simple, conversational Russian, but he also breaks all the rules of good syntax, rebelling against conventions as he did in nearly every other aspect of his life. You often encounter enormously long sentences packed with subordinate clauses, long strings of adjectives, and dense clusters of participles and gerunds, plus a deliberate use of repetition, all of which is hard to convey naturally in English.

RBTH: What are your plans for translation in the future?

R.B.: I am planning to translate more Chekhov stories, and also his plays.

RBTH: Which work would you advise a foreigner to read as their first Russian book?

Rosamund Bartlett was born in London and started learning Russian at the age of 14 at school in London. She holds a doctorate from Oxford, and is the author and editor of several books, including “Wagner and Russia” and “Shostakovich in Context,” as well as biographies of Chekhov and Tolstoy. She has also received recognition as a translator, having edited the first unexpurgated collection of Chekhov’s letters for Penguin Classics and translated two volumes of his stories. Her new translation of “Anna Karenina” is the first to be published by Oxford World’s Classics for 96 years.

R.B.: Probably Lermontov’s “A Hero of Our Time,” one of the earliest Russian novels, which is set in the Caucasus. It is an astonishingly accomplished and sophisticated work, considering the author was only 26 when it was first published in 1840. It is also incredibly modern, being made up of five interlinked stories written with great economy of expression - the limpid writing in the story “Taman” was held up by Chekhov as the most beautiful example of Russian prose. Pechorin, the novel’s ambiguous central character, continues to exert a mysterious hold over readers. Because it’s such a compact work, it’s an excellent place to start before graduating on to the big novels, all of which were influenced by it in some way.

RBTH: How and when did you start to learn Russian?

R.B: I was lucky to have the chance to learn Russian when I was 14 years old at school in London, and I went to Russia for the first time on a school trip two years later. Then I went on to do a Russian degree and had wonderful teachers at the University of Durham who inspired me to continue studying. I learnt most of my Russian, of course, during long stays in the country itself – both during my undergraduate year abroad, and later when I was researching for my doctorate. I was awarded a British Council scholarship to spend a thrilling year at Moscow University in the late 1980s, at the height of glasnost and perestroika, when everything was opening up.

In the recent issue of Russia Beyond the Headlines inside The Telegraph, we've written that 'Anna Karenina' translated by Rosamund Bartlett is to be published in November 2014, we mentioned this date by mistake, this article provides the correct information. We apologize to Mrs Bartlett and to readers.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox