Click to enlarge the image. Drawing by Natalia Maikhaylenko

Eight years ago I didn’t really have any idea of what Russian food was like. I knew borsch, caviar and black bread, but I knew little of the culinary wonders awaiting me, many of which I now miss terribly.

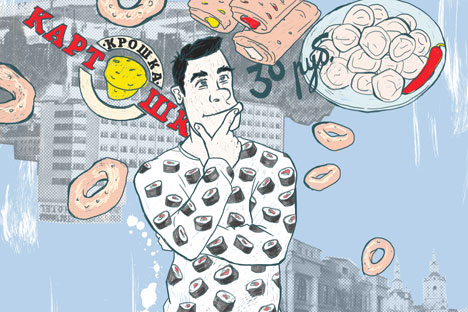

Street Food

Being a poor, newly graduated student, my first year in Russia was not my most affluent. Not being a fan of McDonald's (of which there are plenty, even in tiny towns like Novocherkassk), I often found myself turning to street food for a quick bite to eat between classes.

Top of the list for me were blini(pancakes), filled with any number of delicious ingredients, sweet or savoury. Mushroom, sour cream and cheese was by far my favourite, mostly for its miraculous hangover-easing properties.

I would also often turn to kartoshki (baked potatoes). Though essentially the same as you might get in the UK (see John Mole’s book, I was a Potato Oligarch, to see why that is) these are topped with not one, but up to four unrelated fillings, and why not? Who hasn’t dreamt of having salmon, cheese, pickled mushrooms and bacon all on one cheese and dill-smothered potato?

Then there were shawarma (kebabs), which are as greasy, foul-smelling and as unhealthy as their British cousins. To give you an idea of how “good” these are, an expat friend of mine told me how a half-starved homeless dog by the metro once even turned its nose up at one she’d offered it.

Most evil of all were sloyki. These factory-made little savoury and sweet pastry slices (think Greggs, only much, much worse) can be found being heated in tiny kiosks near metro stations, where their sickly smell chases you down the steps to the station entrance. At just 30 roubles (40p) each, however, they were at least warm and filling in times of desperation.

Know your 'Meat'

It’s worth mentioning that one commonly found sloyki filling is 'meat.' What animal(s) this comes from, however, is never very clear even if you dare ask. These, I found, were best avoided.

Another dish me and any expat with working taste buds avoided, though it is loved by many Russians is kholodets. This disturbing-looking savoury jelly of shredded 'meat' suspended in murky-coloured gelatine is as revolting, in both taste and texture, as it sounds. I guess this is Russia’s equivalent of jellied eels or haggis, not everyone’s cup of tea. Incidentally any Scots visiting Russia should know that for most Russians the words haggis sounds suspiciously similar to a well-known brand of babies' nappies, Huggis. Even if you go to the trouble of explaining to them that the savoury snack is Scotland's national dish and show them one of the small, pungent sacks of stuffing, they'll turn up their noses and ask with an incredulous look: "Is it really edible?" At the same time the vast majority of them will happily tuck into kholodets.

There were, however, many times where a more open approach to carnivorous recipes was a great adventure. Horse steak in Kazan, bear burgers in Novosibirsk and elk jerky in Tyumen were all well worth trying.

When none of this tickled my fancy, I could always turn to vegetarian options, though that was difficult seven or eight years ago, when even the mention of vegetarianism in class caused distress. One student asked: “What’s wrong with you; don’t you want to be a man?” Today non-meat options can be found in many of the larger cities, some of which even have thriving vegetarian restaurant chains.

Eating Out

Traditional Russian restaurants can, naturally, be found all over. Along with a plethora of soups, each delicious in their own way, bar okroshka (a cold soup made from fermented bread, cut meats, cucumber and tons of dill), pelmeni (Russian ravioli) tops my list. Warm, wholesome and delicious, these really help keep off the winter chills.

However, it’s sushi that tops the list of most popular food in Russia by far, and it’s served almost everywhere, from Italian restaurants to Irish pubs. It’s not quite what Japanese would call sushi (in the same way Indians might see British curry), but it is good stuff and was a regular part of my Russian diet.

Georgian cuisine has also seen a huge increase in popularity recently. I loved dipping my khachapuri (cheese-filled bread) in adjika (hot and spicy sauce) and stuffing myself with khinkali (large dumplings). These three dishes are what I miss most about no longer eating out in Russia.

Sweet beyond reason

To say Russians have a sweet tooth is a huge understatement; the inch of sugar at the bottom of virtually very Russian’s teacup speaks for itself.

Along with a huge variety of biscuits and mini cakes k chayu (to have with tea), I had some of the creamiest and sugary cakes I have ever eaten. In many cases it would be better to say these were more cream than cake.

Something I could not fault, however, was Saint Petersburg’s pyshki (ring donuts). Simple and delicious, these are best eaten fresh, on the go.

Of all the things I thought I might miss in Russia, food was not one of them. Over these last couple of months in the UK, however, I’ve really got cravings, so if anyone knows where to get good khachapuri in London, do let me know.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox