Turbulence over Syria's skies

Drawning by Valeriu Kurtu

Drawning by Valeriu Kurtu

The terrorist attacks in Paris and Sinai, and Russia’s earlier decision to get involved in the Syrian Civil War, have raised the stakes in that regional conflict considerably. Already the international efforts in the fight against ISIS are involving new external (and not necessarily regional) actors. Last week alone, the United Kingdom and Germany joined in, although neither had previously demonstrated an enthusiasm for direct involvement. What should we expect? Is an anti-terrorism coalition really being formed? Hardly.

The main problem is that the objectives and tasks of those who form this coalition do not coincide. The situation is a paradoxical one, however: despite the huge differences in the approaches of the external players (notably the United States, France, Russia and the UK), they identify the main enemy in similar terms. This is seen to be ISIS, which should be eliminated or at least stopped. To fulfill this task, active assistance from the regional players – those inside Syria and in the Middle East as a whole – is needed. In theory, they should be carrying out the main military action.

Regional players

But it turns out that their priorities are different. For Turkey, the main threat is the Kurdish issue, which they perceive as far more dangerous than ISIS; so far as Saudi Arabia is concerned, its main fear is that of Iranian Shia expansion rather than of the threats posed by ISIS militants; Iran is engaged in a complex regional game, with ISIS being just one element; Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is not just facing the radical Islamists but a very wide range of opponents. The other countries in the region are desperately trying to maintain control over the situation at home, so they have to maneuver all the time. And they do not always see ISIS as their worst enemy. This state of affairs practically rules out a truly broad coalition. But it does create an unpleasant prospect for the external players. Everybody realizes and admits that ISIS cannot be defeated without a ground operation. The idea is that a ground operation should be conducted by Middle East players, all the more so since the countries of the region invariably condemn “colonialists” for any interference. However, if they do fight, they will be fighting not against terrorism but against each other, which cannot be allowed to happen. So there may be a need for a deeper military involvement on the part of Russia, the US, France and others. Having said that, everybody knows what risks are associated with direct interventions in the Middle East.

Moscow’s motivation

Russia has many motives for its involvement in Syria. The main motive, of course, is the threat of the unchecked spread of terrorism. Another has to do with relations with the incumbent Syrian government, which is Russia’s long-standing partner. Last summer, it became clear that the resources of the ruling regime were close to exhaustion. The Assad regime had turned out to be much more resilient than the West thought it would be back in 2011, but a war of attrition is not something that any country can easily cope with. The fall of Assad would be seen by all as a major setback for Moscow. There were other motives at play, too. For instance, the desire to expand the field of the conversation with the West, which for the past two years was all but limited to the topic of Ukraine and the Minsk process.

At the same time, it is important to view Russia’s actions in a more global context. Moscow has claimed a right, which in the previous 25 years (since the war in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990-91) exclusively belonged to the US. The right to use force to restore international order is the function of a so-called “world policeman”. Russia has entered a sphere where issues of hierarchy are addressed. In a unipolar world, wars fought “for the sake of peace”, that is, wars not aimed at achieving specific and clear goals of one’s own, were waged only by the US with support of its allies. Moscow, having started the military operation in Syria, has changed the alignment of forces and prospects for resolving a major international conflict, with no real practical gains for itself. This is a prerogative of those at the top of the military and political league, who are capable of setting an agenda.

Another important factor is that the conflict in Syria is likely to end the era of a “humanitarian and ideological” approach to resolving local crises. Until recently, an important element of the discussion about sectarian conflicts consisted of such accusations as crimes against one’s own people and the ruthless suppression of protests. A leader who was accused of such behavior was put in the category of rulers who had “lost their legitimacy”, which made any dialogue with them either unnecessary or unacceptable. That is what happened to Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi, and Bashar al-Assad was next on the list. However, now it seems that the humanitarian component is once again giving way to a realistic approach. The black-and-white division into good and bad guys results in a deadlock, and bargaining will have to involve everyone.

Russia has many motives for its involvement in Syria. Source: RIA Novosti

Russia has many motives for its involvement in Syria. Source: RIA Novosti

Open-ended negotiations

One important new element in resolving the Syrian crisis are the talks in Vienna. This is the second (after the marathon of the Iran nuclear talks) instance of open-ended negotiations, when the format of a settlement should emerge in the course of discussion rather than being signed in advance, leaving the sides to debate ways of achieving it. No one knows now what Syria will be like after the war, and in this case this is a good thing. Clearly, there is no guarantee of success, but conceptually it is a more sound path. Unfortunately, the acute Russian-Turkish conflict caused by the downing of the Russian warplane last month was a serious blow to the tentative settlement process that was taking shape in Vienna. Russia has neither the desire nor the resources to wage a lengthy campaign in Syria.

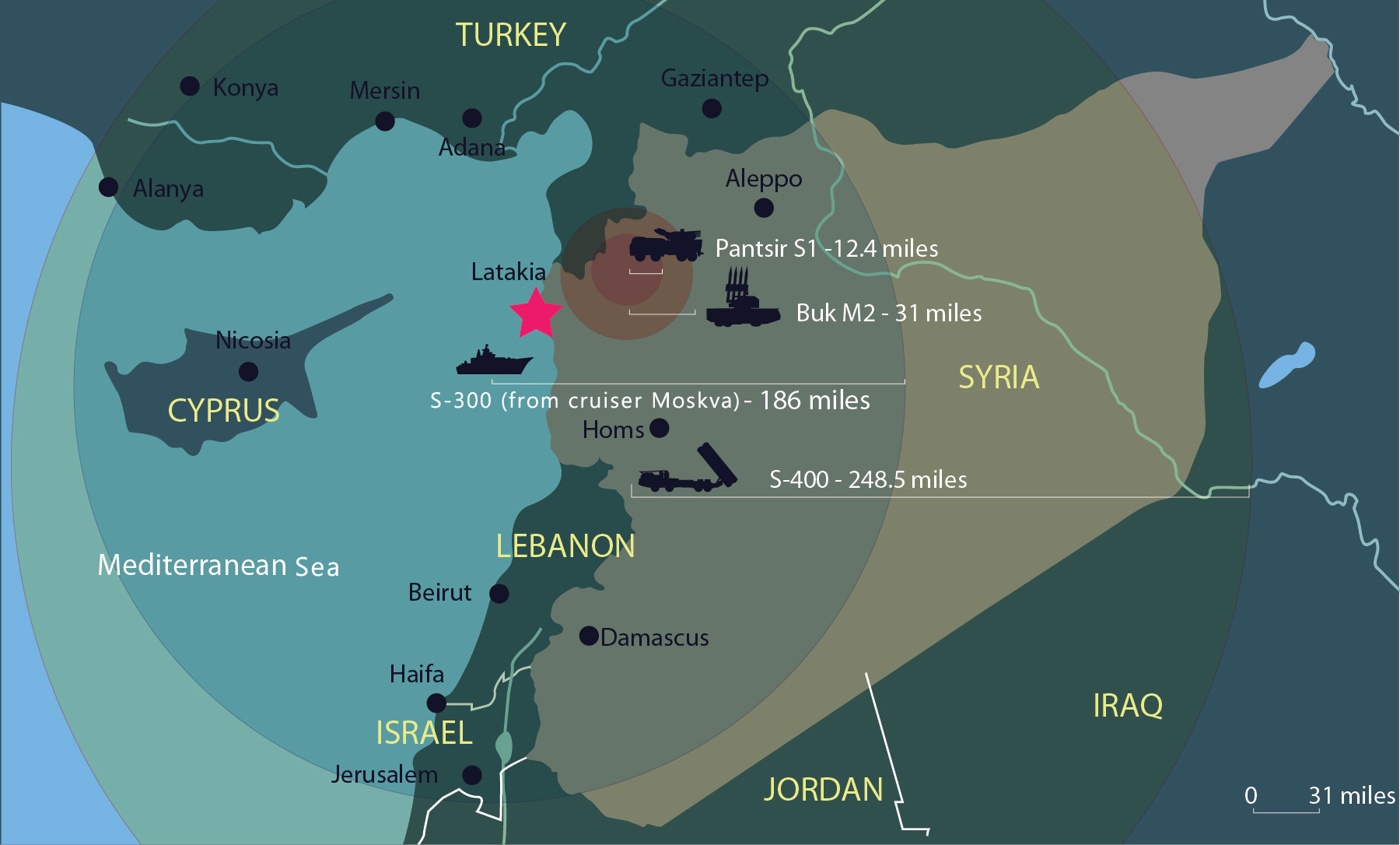

Moscow’s interest in a political solution is as strong as that of the other players. Now, however, a political solution must take into account the fact of a considerable Russian military presence in Syria. It is hard to imagine that the Kremlin will be willing to give up the military infrastructure it has created there so quickly, just like the United States did not fully withdraw from Afghanistan once the mission there was over.

Political shake-up

Russia has a tricky balancing act to perform. First, it has to ensure its future geopolitical presence in Syria, irrespective of the configuration of the authorities there. Second, it must avoid doing any damage to its developing relations with Iran, a major regional partner for the future. For Tehran, preserving the current regime in Syria is essential: it rightly believes that any change will become fatal for Iran’s dominance in Syria. The Syrian saga is perhaps the only topic that cements these relations; in all the other respects, Tehran is viewing Russia with doubt. Third, Russia must make sure not to turn into a great power that is serving Iran’s regional interests, the way, for example, the US for a long time served the interests of Saudi Arabia.

However, the escalation of the past several weeks and the growing scale of events leads to another alarming conclusion. This is no longer just about Syria; this is about the future of the region as a whole. Any settlement in Syria is impossible, therefore, without a political shake-up of the Middle East as a whole. And that is a far larger task, which is fraught with far bigger risks. But it has to be said that these days, Russia is clearly not afraid of risks.

The author is chairman of the Presidium of the Council on Foreign and Defence Policy.

The opinion of the writer may not necessarily reflect the position of RBTH or its staff.

Read more: Will hybrid warfare doctrine draw NATO and Russia further apart?

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox