Soviet Union's collapse casts a long shadow for ex-members

Relic of the past: a broken statue of Lenin at Vaziani military base, a former Soviet military facility, near Tbilisi, Georgia.

APBack in the Eighties, there was a video that used to play on Soviet TV which, to the tune of the famously raucous national anthem, exhibited the country’s prowess. It showed rockets blasting off into space, satellites orbiting the globe, hectic factories, tremendous parades and speeding trains.

The clip was also about people. Or rather the successful ones. Think Yuri Gagarin, Olympic medal-winning athletes and military heroes. And this was the problem. A system ostensibly created to give every citizen a fair shake wound up only benefiting certain groups.

What the USSR’s patriotic propaganda films didn’t show was the drudgery of daily life. The clothes were bland, the buildings grey and the food, at times, wasn’t plentiful in supply or enormous in variety. Yet, despite these negatives, many former Soviet folk would profess to having felt better off in those days, which is perhaps more a reflection on how poorly some ex-republics handled the transition to independence. Not to mention the glaring inequality common to them all. Twenty-five years later, all of the 15 constituent states have gone down different roads. And they’ve achieved varying degrees of success or failure. Statistically the winners are probably the Baltic states, Kazakhstan and Russia itself, while it’s fair to say that Ukraine, Moldova and the central Asian “Stans”continue to struggle.

Differing outcomes

In Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, results have been mixed and Belarus has remained the outlier. Minsk reacted to the USSR’s implosion by more or less ignoring the event. Thus, to this day, the state police are still known as the KGB and – at least in theory – fealty to Lenin’s ideals remains the big idea.

In the Soviet era, Ukrainian Krivoy Rog,which is also known as Krivbas, was an industrial powerhouse. Built to service the mining industry, at 75 miles it is the longest single city in Europe, but has stagnated over the past quarter century.

Viktoria Bocharova’s father migrated from St. Petersburg in the Seventies and her mother was born in Kiev. He returned to Russia 15 years ago, but her mother remains in the Ukrainian city, as does Viktoria.

“My dad had a good job in the Eighties, and a bit of money, and he always used to complain that there was nothing in the shops to buy. Now, here I am, 30 years later and we've plenty of stock in the shopping centres but very little cash to purchase it with! It’s like the theater of the absurd, really,” she says. “Ukrainians have been waiting for two decades for the promised upturn in our fortunes, but it never comes. I think the final straw for most of my peers was two years ago, after Maidan, which destroyed what little economy we had,” Viktoria explains. “The ones who could moved to Russia, or Europe if they were lucky, and the rest of us are stuck here. Although I am planning to go to Krasnodar myself soon.”

Statistics bear out her complaints. In 1991, Ukraine’s GDP was 30 percent higher than in 2014, the fall being mainly due to technological degradation, and it has fallen by another 16 percent since. Seeing little other option, people have voted with their feet and looked elsewhere. Ukraine lost 12 percent of its population between 1990 and 2013 and the UN Population Division forecasts a total below 34 million by 2050. The figure was 51 million in 1991.

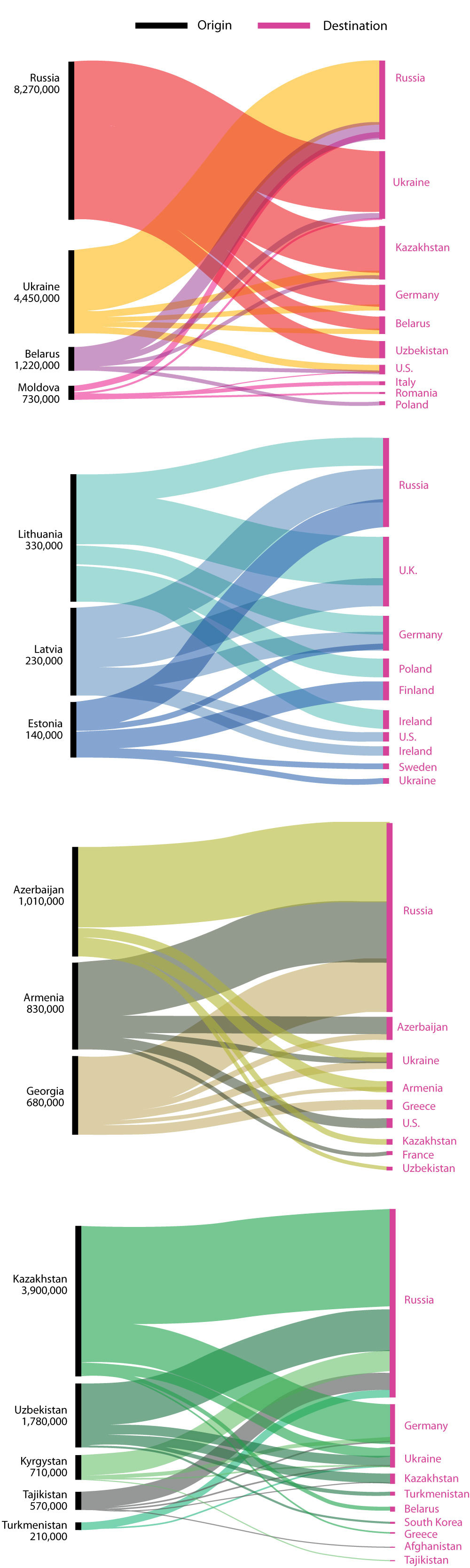

The Baltic states - Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia - have traveled an entirely different road, but also face demographic difficulties. Lithuania, for instance, has lost 24 percent of its people since independence, Latvia 25 percent (up to 2015) and Estonia 19 percent (based on the 2016 headcount). However, rather than scatter across the globe, their emigres almost uniformly moved to more prosperous regions of the European Union or Russia and their homelands hold out hope of attracting a fair portion of them to come back one day. Thus, while the villages and towns of Latvia are stripped of youth today, that may change in the future. Especially if the country succeeds in its ambition to eventually transform its economy through attracting foreign direct investment.“I’ve lived in Ireland for 12 years, and my kids were born here, but I still hold out hope of going home one day,” says Nils, a mechanic in Dublin. “At the very least my two sons know their homeland because they spend every summer with my parents in Jurmala, and we are all EU now so I’m confident they will return to Latvia one day.”

While many young Balts have found better opportunities in the west of Europe, somewhat surprisingly, Russia has been the number one emigration destination for citizens of the three nations. This situation is general across the ex-USSR. For instance, remittances worth £4.2m transferred from Russia to Uzbekistan in 2014 (equal to about a third of state budget revenues) and anywhere between two to four million Ukrainians are believed to live in Russia.

Bakhodir is an Uzbek teacher in Khabarovsk, the capital of Russia’s Far East. "Back home, we have tiny salaries and no rule of law at all. While Russia is not perfect, it has a regard for human rights, people are generally left alone and salaries allow some dignity. I really enjoy living here," he says. "I have a dream to live in England, but as it isn’t a realistic option, Khabarovsk is a perfectly fine compromise."

Central gains for Russia

This brings us to the Russians themselves. Ironically, given that the USSR was essentially an empire controlled by Moscow, there is little doubt that Russia itself has benefited the most from its collapse. Its nominal GDP peaked at $2.07 trillion, compared to $509 billion in 1991. However, the Nineties were a lost, and chaotic, decade and GDP once reached a low of $195.9 billion in that period.

No longer obliged to subsidize far-flung regions or to maintain the kind of security spend the Soviets insisted upon, most of Russia has thrived in recent times, despite the current recession. Marina Tikhomirova, from Vladivostok, has experienced both epochs. Marina was a young doctor when the USSR vanished, and she is now a successful businesswoman in the furniture industry.

“On the one hand, I lament the loss of status for the professions. In the old days, a doctor, teacher or a scientist was the highest person in the community. It was a mark of great status. Now, it’s all changed and the individual with the most money is on top,” Marina reflects. “But I’ve been to Vietnam, Singapore, Saipan, Berlin, Cannes and Miami already in 2016 and it’s still only September. When I was a little communist girl, travel of this sort would have been unthinkable.”Anya Romanenko works for Marina. Originally from a remote village in the Primorsky region, she doesn’t remember the communist era.

“Life isn’t easy in Russia, but I’ve traveled. I’ve been to Korea and China. Also, I have my own car and home and I feel I’ve some kind of future path mapped out,” she enthuses. “My mother, who has worked hard all her life, would consider a trip to Vladivostok to be something special.”

Subscribe to get the hand picked best stories every week

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox