The golden age of Soviet science

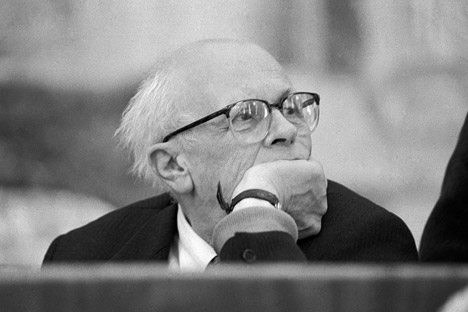

Andrei Sakharov. Source: Yuriy Zaritovskiy / RIA Novosti

The period from the 1950s to the 1970s was a golden age for Soviet science. Yet the field has been in decline ever since.Soviet physicists lived in closed cities and could not travel abroad, but their minds remained free, allowing them to make fundamental scientific breakthroughs.

Why was the Soviet research and development model so effective until the 1970s and what happened afterwards?

The paradox of isolation

Soviet scientists were certainly not public figures. Their institutions were closed and their scientific interests didn't put them in the public eye.

People who worked on large-scale scientific projects – the so-called Big Science - in the USSR, who founded schools of research and their own subculture, were a productive part of Soviet society whose achievements cause many to regret the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The paradox, however, is obvious. Their lifestyle and living conditions were completely unlike that of the rest of Soviet society. Despite being excluded from the country's public life, Soviet scientists provided the country with the technological and intellectual success it needed.

One of the main secrets of the postwar science generation that sent a man into space was that these people, particularly the generation of the 1920s and 1930s, could reconcile themselves to the contradictions and dedicate themselves to helping the country take a leap into the future.

"All of the pioneers had war experience. Some experienced it as children, and some lived through WWII from the first day to the last," says Andrei Zorin, professor at Oxford University, head of the Center for historical and cultural studies of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administrartion.

Related:

Underground Soviet shelters and the secret Metro-2

"And this feeling of being free in the face of tremendous danger, which is often found in the stories of combat veterans, remained with them their whole lives. Many said that they chose to study science because after 1945 that is where the real ‘drive’ was. It was an unexplored field, and the state threw all its resources at it. And don't forget that the work of nuclear physicists was actually very risky. They were in constant physical danger.”

The Soviet scientific intelligentsia of the postwar generation were mobilized by the government to work in science, lived semi-secretly, and created a nuclear power, though not in the traditional liberal understanding.

Nonetheless, at its core, the worldviews of these scientists were essentially predicated upon the values of freedom.

Nobel laureates

The famous Nobel laureate, Andrei Sakharov, was a young scientist when he was assigned to the group led by the famous Soviet theoretical physicist Igor Tamm, whom he amazed during their first meeting with his hypothesis that the uranium should be placed in blocks and not evenly spaced in the reactor.

This was an important breakthrough for nuclear physicists at the time, and Andrei Sakharov was included in the research group that had been tasked with the development of thermonuclear weapons.

Over the next twenty years, Andrei Sakharov worked continuously on top secret projects, first in Moscow and then in a special research center. But the scientist did not become famous for his political views until much later.

The number of employees working in the USSR’s high-tech sector, if you count those working in education and manufacturing, reached 10 million in the 1970s.

According to the most generous estimates, no more than a million people worked in Big Science – a drop in the ocean for a country with a population of 242 million.

In addition, it was hard for scientists to have contact with the outside world because they lived in closed cities and their projects were top secret.

"In 1955 when Blokhintsev, the director of Secret Laboratory B, presented a model of the first nuclear power plant in the world at the Geneva conference, foreign experts were not very impressed with the plant, since they'd seen something similar in the U.S.," says Galina Orlova, a visiting scholar at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, co-director of the Obninsk science city project in the Kaluga Region, and assistant professor of personality psychology at Southern Federal University in the Rostov Region.

But they were amazed that the Soviets could organize so much training for high class personnel in record time. One member of the U.S. delegation noted in the report that "we have nothing like that at the moment."

Education, which one person we interviewed called "lyceum-level education," in reference to the intensive contact between students and teachers that went to the auditorium directly from the lab or test site, was the education of the future. There were no tedious textbooks. This created a fundamentally unique atmosphere.

Scientists give way to careerists

Over time, a school formed, but the intensity gradually weakened. The people who started coming to scientific research institutes no longer had the passion of their predecessors.

These people were only interested in their own narrow field, were pedantic, and interested in making a career for themselves.

"When people today ask where that environment has gone, that generation of people, I would like to answer that, in a sense, they haven't gone anywhere," says Galina Orlova.

"Many of our correspondents born in the 1920s and 30s are still working at their scientific research institutes. However, there is another factor in long careers – when several generations all work in the same industry. By the 1970s, big science was largely the domain of the first mobilized generations.

The descendants of these scientists have chosen different paths. Some remained at the research institute where their fathers and grandfathers worked, while others have emigrated, and the grandson of one of the employees of the Physics and Power Engineering Institute who applied to the Moscow Institute of Physics on the advice of his grandfather even dropped out to become a chef.

Based on material published by Ogonyok and proprietary information.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox