Russian team sports at an ideological crossroads

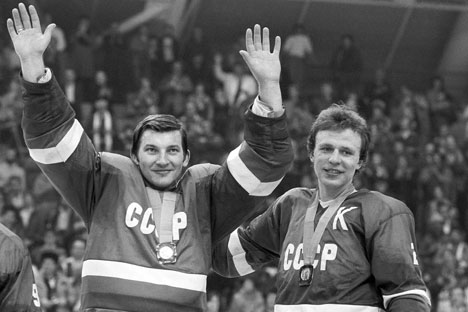

Tretiak and Fetisov won their Olympic gold medals 30 years ago. Source: ITAR-TASS

Thirty years after winning Olympic gold together, two Russian hockey legends have gone head to head.

Off the ice, Vladislav Tretiak, once the world’s greatest goaltender, battled his former teammate and ex-Detroit Red Wings defenseman Viacheslav Fetisov to retain the presidency of the Russian Hockey Federation.

Fetisov’s defensive prowess may have kept his teams from suffering many crushing defeats during his hockey career, but he could do little to stop Tretiak obliterating him 125-11 in the voting.

So what, you might ask? They may be famous, but isn’t this just sports bureaucracy? Not quite.

This battle of two hockey legends highlights a growing divide in Russia on that age-old question in all team sports – club or country?

In hockey, soccer and basketball around the world, this is an issue that has provoked conflicts in the past but now seems all but resolved. Outside of the hysteria every four years for the soccer World Cup or Olympic hockey, players’ primary loyalty is to the clubs who pay them. For many top players, it’s no big deal to skip a game for the national team if they have any concerns about injury.

However, this battle is still being fought in Russia, where it is a relic of the old tradition in which Soviet clubs in any sport were, first and foremost, government-run talent incubators for the all-important national team. At its best, it was a successful system, creating the all-conquering Big Red Machine hockey team in which Tretiak and Fetisov won their Olympic gold medals, but at its worst, it gave politicians huge sway over clubs, leading to frustrated players and cynical fans.

Twenty-three years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, those old ideals are hard to sustain. Russia’s soccer and hockey clubs find themselves fighting two battles at once, hiring foreign stars to chase success in international competitions like the Champions League and the Kontinental Hockey League while also trying to keep the officials in charge of the national team happy. In this week’s hockey federation fight, Tretiak was the establishment candidate, backing Russian President Vladimir Putin’s calls for fewer foreign players in Russian hockey to allow more ice time for local players. Fetisov opposed that idea and stressed the importance of strong clubs – crucial if the Russia-based KHL is to realize its ambition of challenging the NHL for global supremacy.

Tretiak has headed Russia’s hockey federation since 2006, but Fetisov seemed to sense a weakness in him following the Russian national team’s quarter-finals defeat at the Sochi Olympics – by Tretiak’s own admission, not the sort of result his policies should have produced. Fetisov accused Tretiak of letting youth hockey wither away. In other words, there weren’t enough talented young Russians to take advantage even if foreigners were removed. The accusations were to no avail, as Tretiak drummed up overwhelming support from the regional hockey federations who make up his base.

In soccer, the lavishly-paid Italian coach of the Russian national team, Fabio Capello, has said he is keen for more of his World Cup squad to spend time playing abroad. “That is important for experience” of different playing styles and would help the national team, he says. It’s not quite so easy. State-run companies provide cash for Russian clubs to keep stars at home, where quotas on foreign players ensure they can always get a game. The result: Russia is the only team at the World Cup with all 23 players based in its home league. Just two of them have ever played in one of Europe’s top four leagues.

There’s also a power behind the scenes – an éminence grise – Sports Minister Vitaly Mutko. Most Russian soccer and hockey clubs spend more on star players – Russians and foreigners – than they could ever earn from ticket sales and TV rights. Government bodies make up the shortfall, and as the man in charge of state sports policy, Mutko has vast influence. That even means an effective veto on new national team coaches.

As always, some kind of compromise will be found. The clubs’ backers and the national team boosters aren’t zealots, after all. Tretiak will have to devote time to the clubs, just as Fetisov, if elected, would have had to look after the national team.

Whichever way Russia’s two biggest sports, soccer and hockey, choose, officials could earn big rewards or face serious consequences for failure. Russia will host the Ice Hockey World Championship in 2016 and the FIFA World Cup two years later. If the national team is not up to scratch, heads will roll.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox