Who are Russia's New Tolstoy and Dostoevsky?

Head of Glas publishing house

Alexei Pavlovsky / RIA NovostiDossier

Natasha Perova answered the questions of RBTH cultural editor Svetlana Smetanina.

You started publishing Russian literature in English translation when there was still a Soviet Union. How did the publishing system work then and how has it changed since perestroika?

In Soviet times, many books were translated into foreign languages. But, of course, strict censorship existed. The books translated were correct from the point of view of Soviet ideology: Russian classics, memoirs by Soviet public figures, as well as volumes of Marxist-Leninist teachings. The print runs were huge. Naturally, they were determined not by reader demand, but by directives from on high. Where those print runs went, one can only guess. A friend once told me an extraordinary story. Every year a certain Soviet embassy would buy a fishing net, rent a boat, and dump all of that pulp into the ocean. There wasn't any other way to get rid of it; there was nowhere to store tons of unneeded books. And our editions were cheap to boot - for instance, the English edition of the journal Soviet Literature was sold for just $2 a copy. It was only when I became its editor that I realized what enormous expenditures were being entirely subsidized by the state. By then perestroika had begun and formerly forbidden books were suddenly not forbidden anymore - Grossman, Platonov, Solzhenitsyn. We began printing them in Soviet Literature: the interest was considerable. It seemed that now we could finally give foreign readers what was really of importance to them, as opposed to what the Party ordered up. But then it turned out that the state was no longer willing to sponsor Russian literature abroad - there simply wasn't the money. The Soviet Writers' Union (under whose auspices Soviet Literature had existed) collapsed and the journal was shut down by the state, saying it was unprofitable. Soon all the other publishers that had been translating Russian literature into foreign languages also closed. I decided to start my own, non-commercial publishing house. I suppose my enthusiasm was in part ignorance of the difficult path ahead.

When you became a publisher, how did you go about choosing authors?

I distributed a questionnaire to Soviet critics asking them which authors they considered the most talented and promising.

What sort of an audience is there for Russian literature in England and America?

The audience for Russian literature is very limited. If 60-70 percent of the literature published in Russia is in translation, then only 2-3 percent is in translation in England and America - from all foreign languages combined. To enter that market is very difficult and the print runs for translated works are usually small. GLAS has contracts with book distributors in the U.S. and the U.K.

Books that do well in Russia aren't necessarily popular in the West. Many of our famous writers - Vasily Aksyonov, for example - have complained that the foreign reader often doesn't

understand them. How do you explain that?

I always say to Russian writers who want to be read abroad that the foreign reader doesn't understand them because they are addressing their accustomed Russian audience. Russian literature developed in isolation; as a result it has a hard time promoting itself in the West. That isolation primarily affected the mentality of the language. What a Russian reader gets right away must be rephrased for a Western reader and explained.

Success is indeed difficult to predict. GLAS published a book called "The Diary of a Soviet Schoolgirl." It's the diary of a real person. She was arrested because of that diary in the 1930s, when she was 17. This book, to my surprise, became a bestseller. It was translated into 20 languages! We had a similar success with Arkady Babchenko's book about the war in Chechnya. It has already come out in many languages and will eventually have editions in 15 countries.

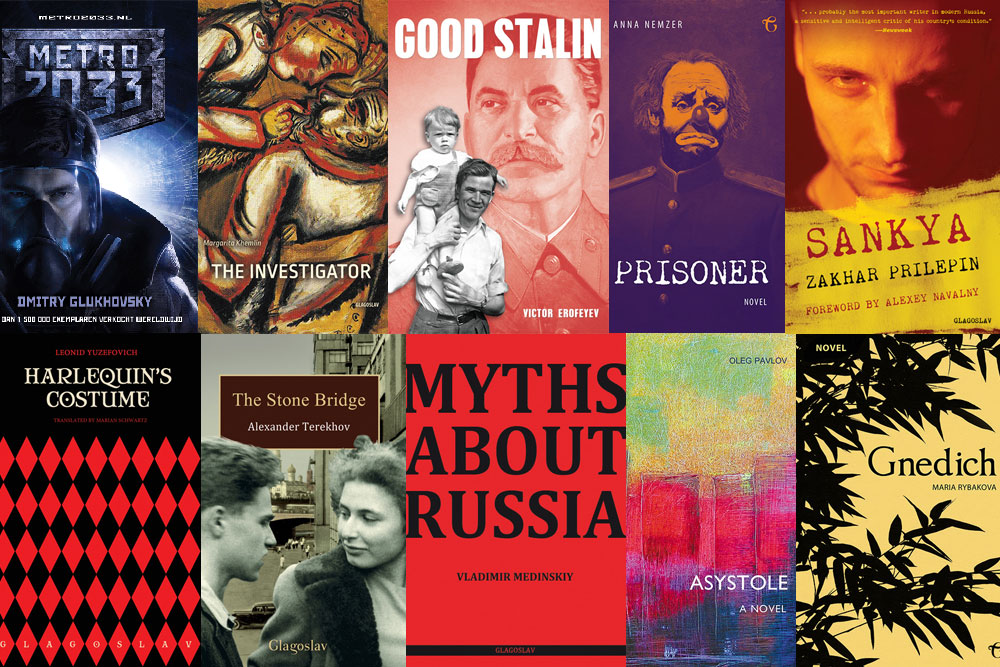

There are several constant key themes in Russian literature which also interest Western readers. The theme of women. The Jewish theme: the survival of a foreigner in a different culture. Our latest book, a novel by Maria Galina, a very compelling writer, is in the genre of intellectual fantasy, now highly popular with young people. At my suggestion, the UK publisher of Alma Books recently published Alexander Terekhov's brilliant novel "The Rat-killer" and now wants to do a Russian series. He has already bought the rights to a massive novel by Dmitry Bykov (another GLAS author). GLAS has published over 100 Russian authors to date. And we're still looking.

In many countries - for example, Sweden, America, Great Britain - the government supports the publication of books by national authors abroad. Does Russia do something similar?

Unfortunately, there is no state support for works by Russian authors published abroad, propaganda, in the good sense, of one's own culture. My job, as I see it, is to promote the Russian literature in which I believe. GLAS acts as a cultural bridge between Russia and English-speaking countries. When we first started out, many translators worked for nothing so as to support GLAS. Today many of them are under contract to large publishers in the West. GLAS was (and is) a sort of school for translators. Of course, it wasn't easy. But every time I begin to despair and consider closing GLAS, something happens. A sponsor suddenly appears for a specific book. Or I receive a warm letter of thanks from a foreign reader. Or GLAS is awarded the Rossica Prize for the best literary translation from Russian into English. All of which tells me that we're needed. And gives me strength.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox