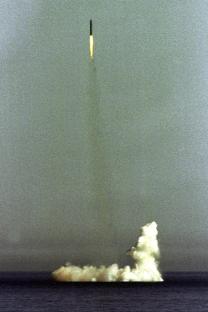

Bulava's triumphant salvo

|

| An intercontinental ballistic missile blasts off from a submarine aimed at a target some 6,000 km (3,700 miles) away in the remote Kamchatka peninsula in Russia's Far East during naval exercises August 21. Source: Reuters / Vostock Photo |

The submarine Yury Dolgoruky fired a salvo of two Bulava-30 intercontinental missiles from beneath the ice-bound White Sea. The Defense Ministry reported that the launch went smoothly; all the warheads covered a distance of nearly 5,000 miles and hit targets on the Kura test range on the Kamchatka Peninsula. The exact number of warheads was not released, but it is believed to be somewhere between six and 10.

It was the first double launch of the 18 official Bulava tests, and it enabled President Dmitry Medvedev, who is also Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Armed Forces to declare at a Kremlin reception that the Bulava tests had been completed and that both the missile and its carrier would soon be deployed by the Russian Navy.

The president did not give the exact date, but experts familiar with the situation in the country’s defense establishment claim it might happen at any time, and will certainly take place in the early months of 2012. Everything is ready: the submarine cruiser is on high alert; the missile was launched from under water four times without any mistakes in 2011; the dock at the Vilyuchinsk naval base on Kamchatka, where the Dolgoruky will be based, is ready as are comfortable houses for the ship’s officers and their families and modern dormitories for unmarried contract personnel and conscripted seamen.

This is the end of the story, but the history of the creation of the strategic Bulava-30 missile and the strategic nuclear submarine cruiser Yury Dolgoruky is worth telling from the beginning. The project was launched in the mid-1990s at the Rubin St. Petersburg Central Design Bureau for Marine Engineering, but with a different missile in mind. This missile was called Bark and had been developed by the Viktor Makeyev Miassk Central Design Office. But the first three launches of Bark from a stand in the White Sea all failed. In addition, Bark was almost two and a half times bigger than the military had commissioned. Instead of the maximum 40 tons, the missile weighed almost 90 tons.

It is unknown why the designers ignored the assigned size specifications. Perhaps they could not follow them, or perhaps they did not want to. What is known is that, when the Akula (Typhoon) class strategic nuclear submarine was designed in the mid-1970s, Viktor Makeyev, the general designer of that missile submarines, also overshot the weight parameters; the missile did not fit into the silos. But the designer’s reputation was so high that the defense department of the Communist Party Central Committee ordered the chief designer of the Akula class nuclear submarine to increase the size of the ship to enable it to accommodate the missiles. He complied, and the Typhoon was entered in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s biggest submarine. It was longer than two football fields, and the noise it made when moving under water earned it the nickname of “mooing ocean cow.”

But Russia in the 1990s, unlike the Soviet Union 1970s, had neither the economic nor the technical capability to build such huge nuclear submarines. That is why the country’s leaders commissioned the missile for the new nuclear submarine from the Moscow Thermal Technology Institute and it’s chief designer Yury Solomonov, who had never built submarine-launched missiles but, in the cash-strapped economy of the 1990s, managed to build and deploy a new strategic missile, the Topol-M. It was thought that the new marine missile would be in many ways compatible with Topol, but things did not work out that way.

There were many setbacks in the creation of the missile – first among them the fact that many top defense specialists had quit and the country’s defense industry was in a critical state. Additionally, many defense industries making missiles had been privatized and changed their business, and then, the institute and the plant could not obtain the materials needed to build the Bulava.

But eventually the situation changed, and the Rubin design studio, the Moscow Thermal Technology Institute and the Northern Machine Building Enterprise in managed to overcome all these odds in their construction of the Bulava and the Yury Dolguruky.

In addition to the Dolgoruky, the Alexander Nevsky nuclear submarine will also be deployed. Like the flagship, it will have 16 missile silos. In the pipeline are two more strategic nuclear submarines, Vladimir Monomakh and St. Nicholas, which will have 20 Bulava silos each. By 2020, four more submarines will be built. They have yet to be named, but they will carry 20 independently-targeted multiple warheads, not necessarily for combat use, but to cool some hot heads. Historical experience shows that, so far, this has proved indispensable.

Viktor Litovkin is the editor-in-chief of the Russian journal “Independent Military Review”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox