Andrei Tarkovsky: The filmmaker who saw an angel

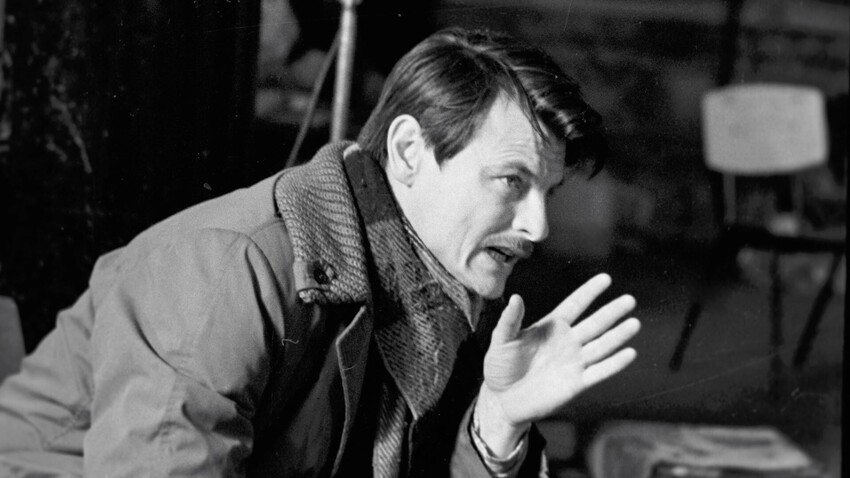

Despite numerous ideological difficulties, Russian film director Andrei Tarkovsky was able to make his “seven-and-a-half” films (seven full-length feature films, one short, and one documentary) the way he wanted. That way, he managed to not only express the beauty of his soul, but also change the course of world cinematography. As Tarkovsky himself used to say, he spent his whole life making just one film - a film about man and the search for truth, for the ideal. Tarkovsky, a student of Mikhail Rom, was a leading figure among the new breed of talented directors who came to film in the early 1960s, bringing with them their own topics, problems, and worldview.

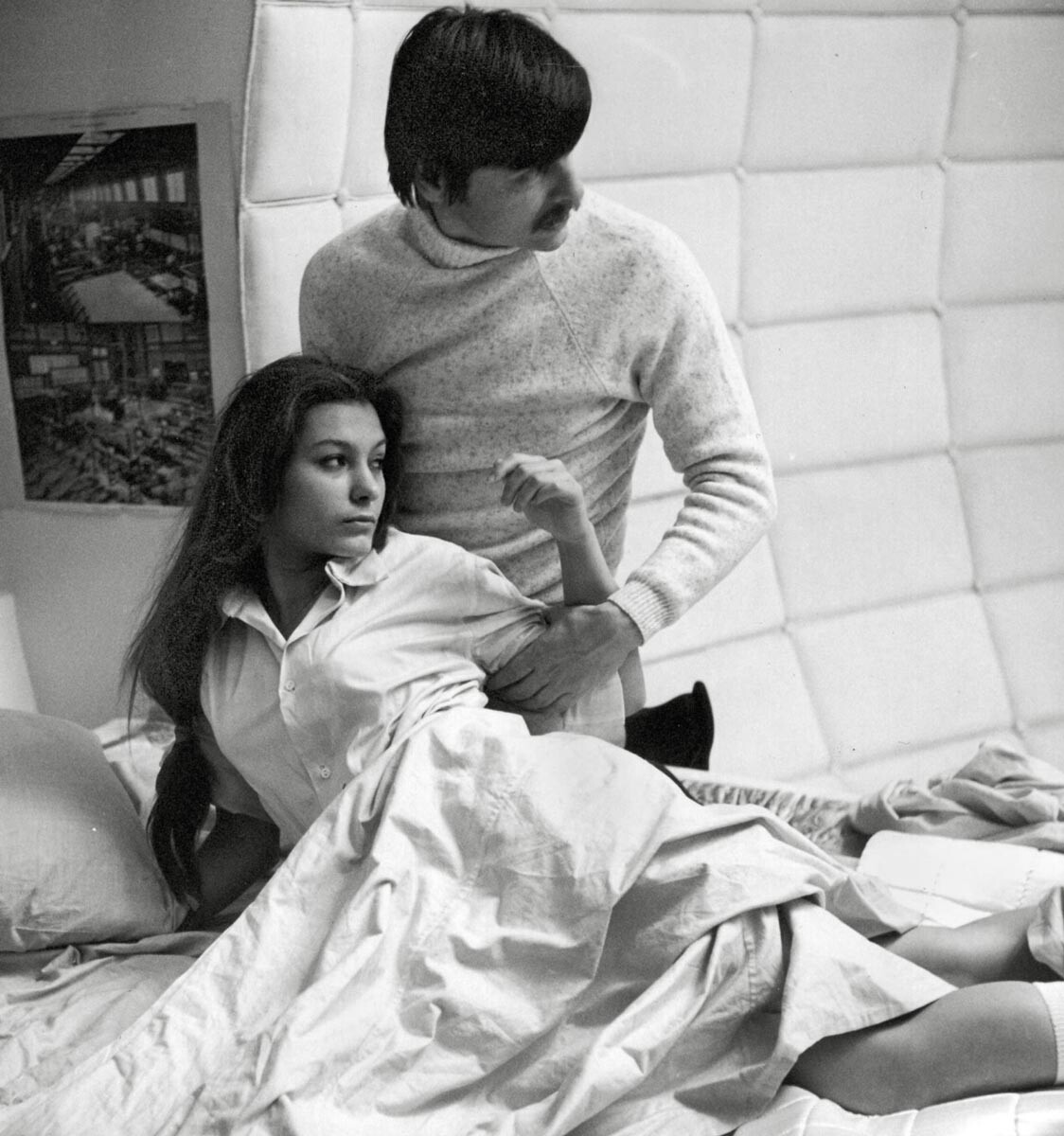

Source: Legion Media

Source: Legion Media

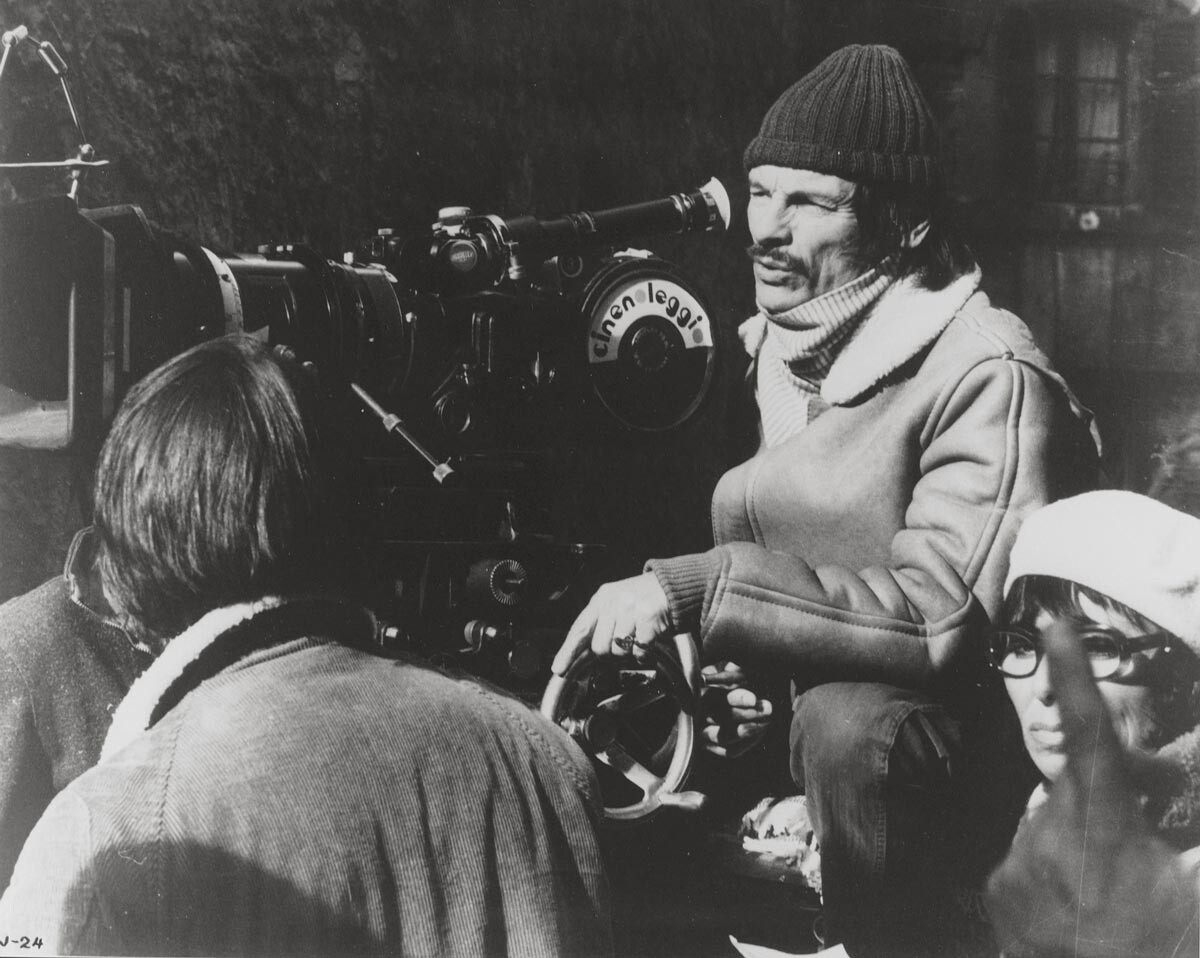

Tarkovsky’s feature-length debut, “Ivan’s Childhood,” was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. He followed this auspicious beginning with “Andrei Rublev,” “Solaris,” “Mirror,” and “Stalker”. He made three more films while in forced exile from the Soviet Union: “Nostalghia,” “The Sacrifice,” and the full-length documentary “Voyage in Time,” which he shot with Tonino Guerra. As for how Tarkovsky was received in his home country, the numbers speak for themselves: “Stalker” came out in 1980, with just 196 prints, only three of which were allotted for the whole of Moscow. But within months of its release, two million people had seen the film. In the early 1980s, Tarkovsky was invited to shoot a movie in Italy. He never returned to Russia. Although “Nostalghia,” which was written with Guerra, was, on the whole, apolitical, it still caused suspicion. So when the opportunity to work abroad arose, Tarkovsky jumped at the chance. The Soviet authorities made repeated demands that he return, but Tarkovsky refused and was declared a traitor.

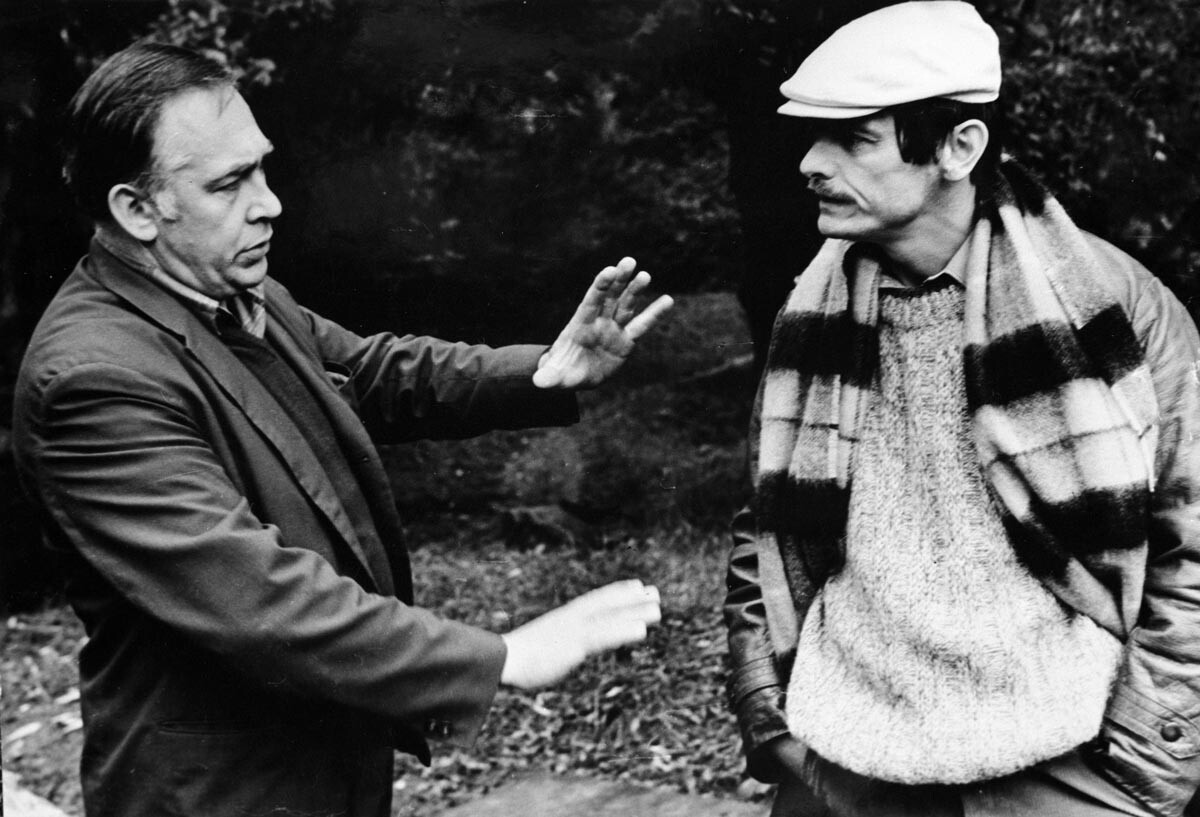

Source: Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Source: Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

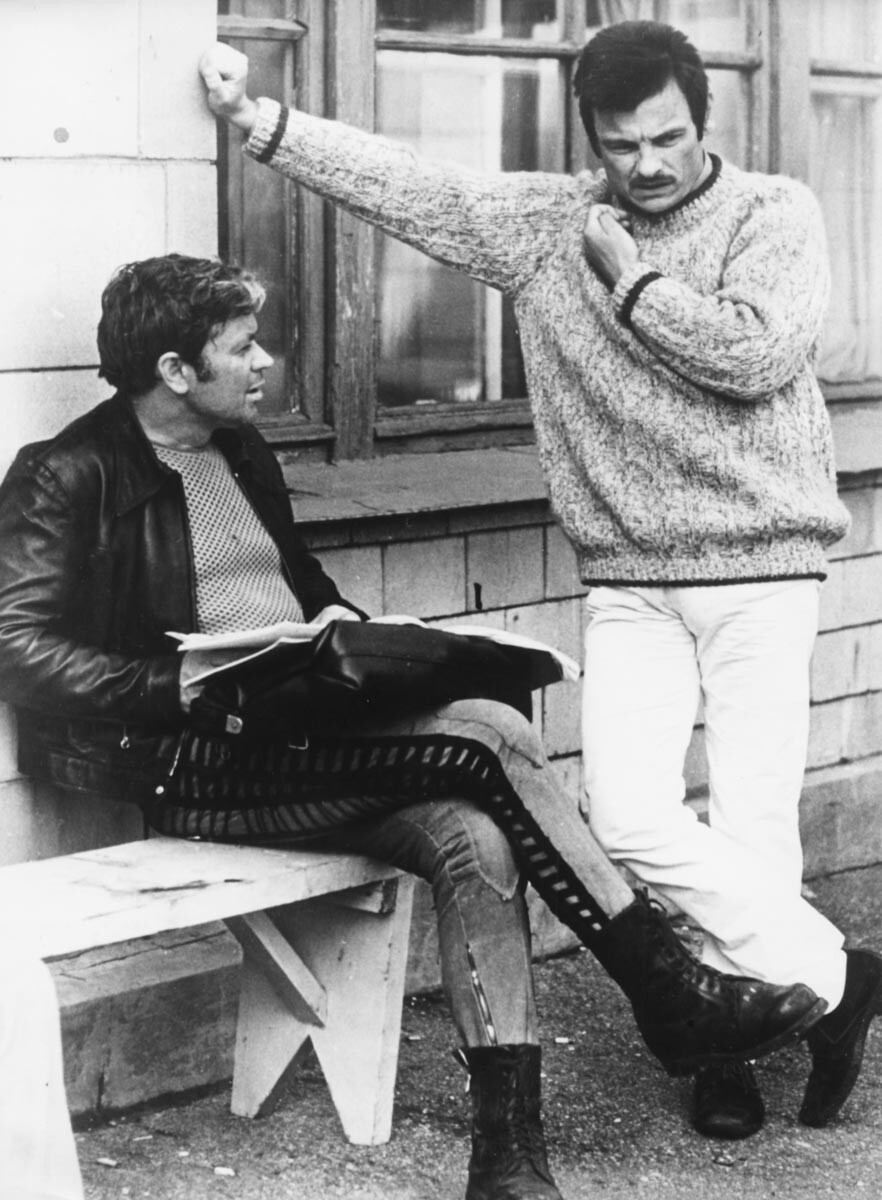

Polish film director Krzysztof Zanussi, who once toured the United States with Tarkovsky, described a meet-and-greet with audience members at which a young American asked him: “What should I do to be happy?” Tarkovsky replied: “First, you have to understand what you live for. What’s your purpose in life? Why were you born in precisely this day and age? What is your calling in life? First you have to get to the bottom of this. And happiness will either come, or it will not come.”

Naum Kleiman, director of the State Cinema Museum in Moscow, argues that Tarkovsky the director came at the perfect time – in 1962: “We had reached an impasse of sorts in our country: the Khrushchev ‘thaw’ was either to gather momentum, or be stamped out altogether. And it was here, at this turning point, that Tarkovsky and his questions appeared. It is well known that, in Spanish, question marks are put before and after the sentence. This is also true of Tarkovsky: He always opens with a question, and leaves us with a question in the end, a question addressed to each of us separately, rather than to society as a whole.”

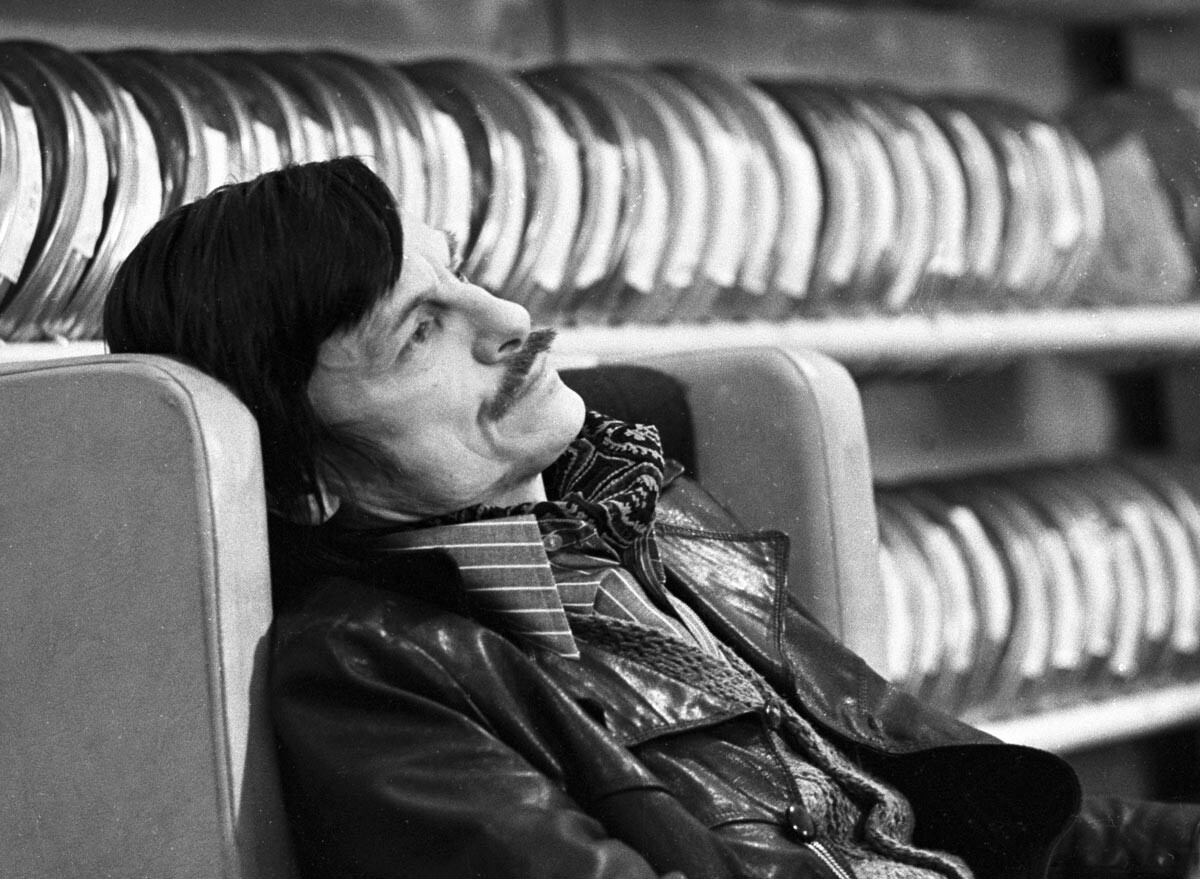

Source: Metelitsa/Sputnik

Source: Metelitsa/Sputnik

The filmmaker used to stress that the main message of his existential works lay in the moral issues they raised. “Once we have reached a new level of cognition, we have to move our other leg to a new level of morality as well,” Tarkovsky said. “I wanted to prove with my work [Solaris] that the issue of moral strength and moral integrity penetrates our entire existence; it manifests itself even in those areas which seemingly have nothing to do with morals, like space exploration, the study of the objective world, and so on”

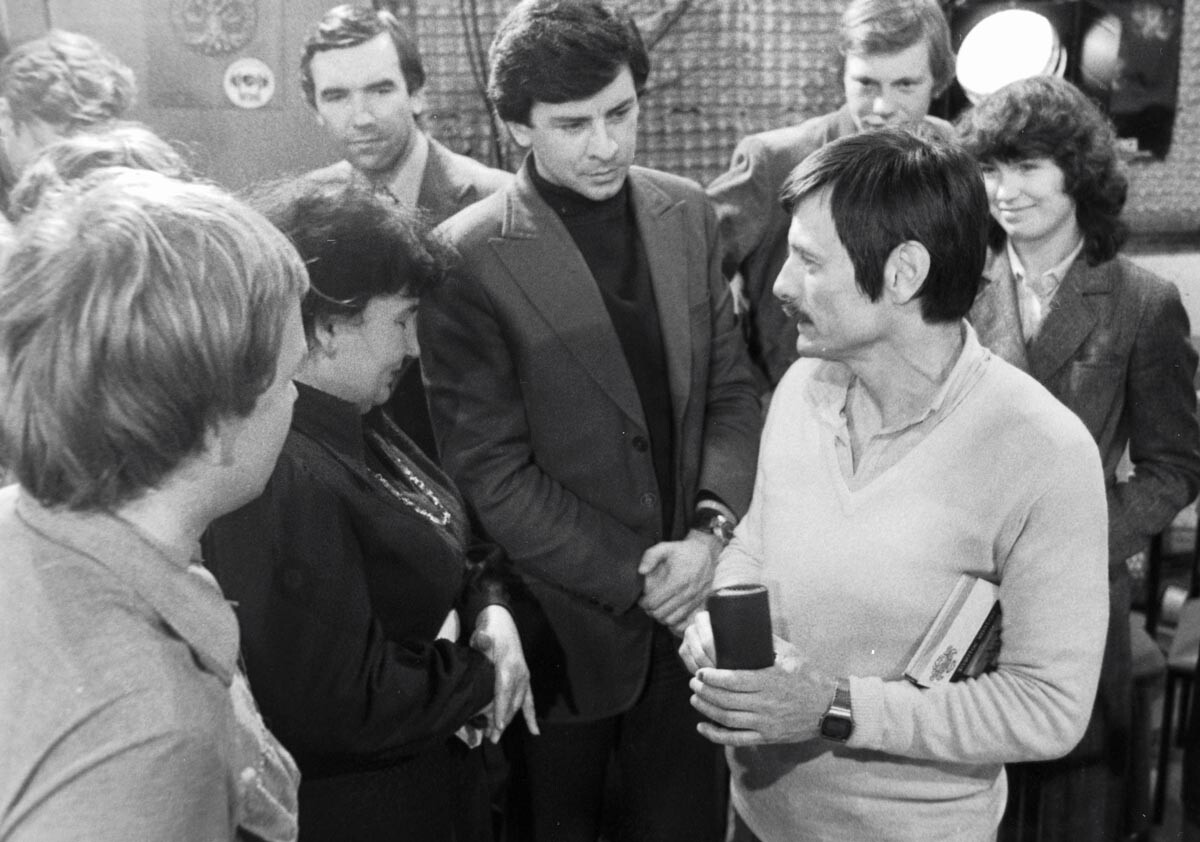

Nikolai Burlyaev, a People’s Artist of Russia who was cast in Tarkovsky’s films, said the filmmaker was deeply religious, that he was forever searching for, and moving towards, God: “This can be felt in every film he made,” Burlyaev said.

Legion Media

Legion Media

Actress Natalya Bondarchuk, who considers Tarkovsky her teacher, said of him: “Andrei Tarkovsky continues to hold the flag of genuine and eternal art.. All of Andrei’s films, regardless of the time in which they are set, point towards the future, to eternity, to God.”

Tarkovsky died of cancer in France in December 1986. He was buried in the Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois cemetery not far from Paris. The following words are engraved on his tombstone: “To the man who saw an angel.” Visitors to his grave will notice that it looks like a frame of film. A few flower pots are planted around the rectangular, dark-soiled plot, a tree leans over the tombstone shedding its leaves evenly on the tomb, a braid of white pearls encircles the cross – a necklace left by the preeminent Soviet filmmaker and scriptwriter, Sergei Paradzhanov.

Mikhail Ozersky/Sputnik

Mikhail Ozersky/Sputnik

The tombstone of another film director, Japan’s Yasujiro Ozu, also features an inscription with which he wanted to be associated after his death. It is the Japanese symbol for “nothing.” It would seem that an ocean divides the two inscriptions both geographically (since Ozu is buried in Japan, in a cemetery close to the Kita-Kamakura railway station) and metaphysically. Meanwhile, their works, their view of reality, were to a large extent related. Even Wim Wenders, the great creator of the road movie, dedicated his “Wings of Desire” to Tarkovsky and Ozu (along with France’s François Truffaut), noting that these three film producers focused “on the enduring truth, which lasted from the first scene to the last.”

Soloviev/Sputnik

Soloviev/Sputnik

Tarkovsky believed that film should contribute to the process of improving the lives of people worldwide, and all his films reflect his commitment to this idea.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox