University of Michigan at Ann Arbor is the very place where Russian and Soviet writers such as Vasily Aksyonov and Joseph Brodsky spent their time after their emigration from the Soviet Union. Source: Press Photo

Inspiration often comes from unexpected places. And you may not know it has happened until long after the fact.

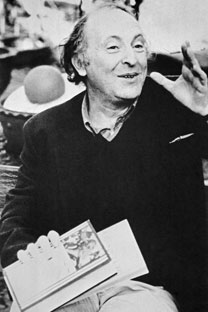

One of the most inspirational people in my life was a scholar and publisher whom I never met. His name was Carl R. Proffer and I can't imagine living the life I have without him.

Along with his wife Ellendea C. Proffer, he founded Ardis Publishers in the early 1970s. This was a case of someone taking the idea of a publishing "house" quite literarily. The Proffers began printing unpublishable Soviet and Russian literature at home and selling it by mail. Here you could read the latest stories, novels and poems by contemporary writers Joseph Brodsky, Vasily Aksyonov and Andrei Bitov, to say nothing of banned works by Osip Mandelstam, Mikhail Bulgakov, Nikolai Erdman and many others from the early Soviet period. By the late 1970s I was unloading as much of my meager paychecks on books from Ardis as I was on records by Van Morrison, Bob Dylan and the Kinks.

One of my greatest joys in those years was receiving the latest edition of the Proffer-edited almanac Russian Literature Triquarterly in the mail. This was a scholarly journal like no other, past or present. There wasn't a stuffy word in it. Each issue was jam-packed with incredible new translations, fascinating essays, groundbreaking memoirs and eye-opening scholarship. Each deliciously fat issue was also accompanied by oodles of rare, historical photographs and fabulous drawings and caricatures. RLT was an unsurpassed treasure trove of Russian letters.

It was long one of my dreams to be published in RLT. I was still putting together materials for a piece on the playwright Nikolai Erdman when 20 years ago I began writing for The Moscow Times. So much for that dream.

I happened to be at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor last week, the very place where Carl Proffer taught and published his books until his death at the age of 46 in 1984. I was asked to speak to some graduate students and faculty members about contemporary Russian drama and while I was in the Modern Languages building I took a little tour around the Slavic Department. I passed by Proffer's old office and, by the kindness of Nina Shkolnik and Vitalij Shevoroshkin, I even had the opportunity to step inside the office once occupied by Nobel Prize-winning poet Joseph Brodsky.

|

| Joseph Brodsky. Source: ITAR-TASS |

Brodsky, you see, came to Ann Arbor because of Proffer. It was his very first stop in the United States after he was deported from the Soviet Union in 1972.

Herbert Eagle, presently the chair of the Slavic Department, told how he remembered seeing Brodsky come in as a "young, red-haired" guy. Eagle explained that Proffer happened to be in Leningrad with Brodsky at the moment when Brodsky received news he would be "allowed" to emigrate.

Proffer wasted no time and set the poet up with a job. He convinced the University of Michigan to grant Brodsky the status of poet in residence, the first writer in 30 years to have that honor at the university. His only predecessor was Robert Frost.

Invited in by Professor Shevoroshkin, I spent a few moments in Brodsky's former office. It is now entirely the domain of a linguist, but a few items have been left as they were the last time Brodsky stepped out into the corridor in 1980. A random gallery of postcards and pictures that Brodsky scotch-taped to the inside of the door still hang there helter-skelter. They include photos of an old Soviet china plate, the Venice canals, a view of St. Petersburg, and several simple designs that surely had little meaning for anyone but the poet.

Shevoroshkin explained that numerous items have fallen off the door over the years but that he hasn't gotten around to taping them back up. "I've got to do that sometime," he said with a smile suggesting he may never get around to it.

|

| Vasily Aksyonov. Source: ITAR-TASS |

Important as his service to Brodsky was, bringing the poet to Ann Arbor was only one of Proffer's many significant contributions in bringing Russian literature to America. I well remember that when Vasily Aksyonov was deported from the Soviet Union in 1980, his first stop was Ann Arbor. By that time, for those of us following events, it was the natural, the only, destination Aksyonov could have had in America. Not New York, not Los Angeles, but Ann Arbor, Michigan. Where Carl and Ellendea Proffer were located.

A year earlier I met the poet Bulat Okudzhava and the novelist Sasha Sokolov in California. Both had been published by the Proffers at Ardis.

There isn't that much of substance about the Proffers on the Internet, and that is an injustice. You can read where Ellendea was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 1989, a well-deserved award for her work at Ardis. There is a paragraph about Carl on the web page of the Slavic Department at University of Michigan.

But there is definitely something missing. For those of us coming to Russian literature in the 1970s and 1980s, Carl and Ellendea Proffer were Russian literature. As long as people continue to read Joseph Brodsky, Vasily Aksyonov, Andrei Bitov, Sasha Sokolov and many others, their contribution will continue to affect us.

First published in the Moscow Times.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox