Building BRICS on discontent

Drawing by Niyaz Karim

Can BRICS, an organization uniting such different countries as Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, become an international player? An economist would say no, and BRICS was, in a way, “created” by an economist – Jim O’Neil, a Goldman Sachs analyst, identified the four countries (BRIC) as the world’s fastest rising economic powers. South Africa joined last year because of its growing economic weight and an obviously leading role in Africa. This continent, the world’s biggest cluster of developing nations, was becoming too important globally for it not to be represented in the initial BRIC.

Not only an economist, but also a scholar of the world’s cultures would say no. He would remind us that the Chinese and Indians are not on good terms and that Russia, still widely snubbed by its Western neighbors as “ not really European,” is not seen as truly Asian by its eastern neighbors neither. As for Brazil and South Africa, these two countries seem to be so far removed from each other and from the “traditional” global centers of the EU and the US, that geography is widely seen as the main impediment for their tourism industries.

And yet, the leaders of the BRICS’ members, obviously busy people, manage to convene annual summits. Their foreign ministers and other diplomats meet even more often and manage to come out with joint statements. This despite China’s lack of enthusiasm for India’s permanent membership in the UN’s Security Council. In short, what glues these very disparate giants together?

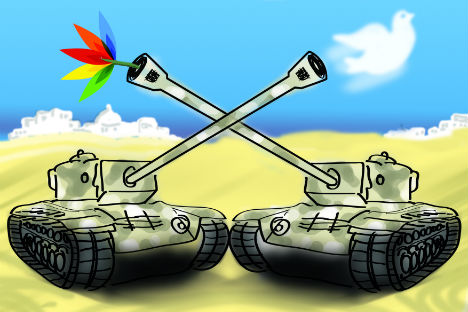

The answer is – discontent with the policy of the world’s “traditional” leaders. Even the timing of the BRICS’ two recent summit meetings is evocative. The first one, in China’s Hainan, took place during the Libyan crisis. The second one, in New Delhi, concerned itself, among other things, with the troubling developments in Syria.

Read more:

Russia as a “third force” in the strategic confrontation between India and China

It became obvious already during last year’s summit of BRICS in Hainan that BRICS did not share the West’s prevalent enthusiasm about the “Arab spring” seeing more trouble than gains ahead. At the moment when Washington, Brussels and other European capitals were applauding the toppling of Mubarak in Egypt and encouraging insurgents in Libya, BRICS’s statement on the matter resembled a bucket of cold water thrown into a jubilant crowd. The five BRICS’ leaders, one of whom, South Africa’s Jacob Zuma, led the African Union’s effort to achieve a negotiated settlement between Gaddhafi and his enemies, expressed “deep concern” about the developments in North Africa. Note it: it was concern in spring 2011 – when the fashion of the day was jubilation about the “coming democracy.”

The continuing war of militias in Libya, troublesome developments in Egypt with anti-Christian pogroms and tensions between the Islamists and the military, all of these events have proven at least some of BRICS’ concerns to be reasonable. And the most recent summit of BRICS in New Delhi took place with Russia and China being castigated by the head of American diplomacy, Mrs. Clinton, as the main block on the road to peace and democracy in Syria. Alas, we heard it before: in Libya, Russia’s and China’s acquiescence to a dimly worded resolution of the UN Security Council led to a full-blown Western intervention in Libya. In view of that story, there are some reasons for Moscow and Beijing to prefer seeing Mrs. Clinton unhappy to seeing the Libyan story repeat itself.

So, it is the West’s interventionism that puts these indeed different nations together, cementing the BRICS better than the old leftist illusions, which were in some form present in all of these countries during the twentieth century. By the way, even our common tragic communist past is from time to time used by the West as a tool for lessening the legitimate role of Russia and China on the world stage – as if Mao’s or Stalin’s crimes made the new generations of Russians and Chinese somehow inferior to the new generation of, say, Latvians. In fact, this policy of the US and the EU became one more reason for Russia and China – two countries whose interests conflict much more than, say, the objective interests of Russia and the EU countries – to stand side by side on such issues as Syria or the former Yugoslavia.

Alas, the West’s interventionism is not limited to such cases as Libya or Syria. The Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff recently expressed dismay over Washington’s currency policy – dollar’s devaluation makes the exports of Brazil and other developing countries to the US extremely limited. The response was a cold shoulder given to Rousseff during her recent visit to Washington. Add to it Obama’s refusal to review the very possibility of lifting the economic blockade of Cuba – voiced during the recent Summit of the Americas in Cartagena, Colombia, it provoked outrage not only in Brazil, but just about in all Latin American countries. Colombia’s president had to make a special trip to La Habana to excuse himself before the Cuba’s Raul Castro. As for the “currency wars,” here is statistics: if Brazil’s real grew to dollar by 2 percent, Russia’s ruble jumped 9.2 percent. No wonder there are no Russian exports to the US.

Does it mean that Brazil, together with other Russia, India and China, does not wish democracy for Cuba or Syria? Of course we want democracy for these countries, we are no less humanist than our Western neighbors. But we don’t want it to be “exported” by military interventions and “salaries” from the US for defecting Syrian soldiers (a possibility discussed at the recent summit of “friends of Syria” in Istanbul). With such “friends,” as the ones we saw in Istanbul, who needs enemies? That is why the disparate BRICS countries become REAL friends – in need.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox