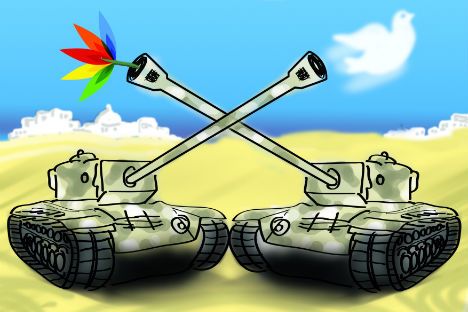

Strange bedfellows escaping the unipolar world

Drawing by Niyaz Karim

An economist would say “no.” BRICS began life as an economic designation – Goldman Sachs analyst Jim O’Neill coined the term BRIC in 2001 to identify the world’s fastest-growing economic powers; South Africa was added last year because of its growing economic weight. An economist would hold that the group’s strength lies in its presence in the global economy, nothing else.

Related:

A scholar of the world’s cultures would also say “no.” Such a scholar would note that China and India are not on particularly good terms, while Russia is viewed warily by both East and West. As for Brazil and South Africa, they are so far removed from each other and from the traditional global centers of the EU and the U.S., that it seems impossible for such countries on the margins to have much global influence.

And yet, the leaders of the BRICS countries manage to convene annual summits and produce joint statements that seem to be leading the organization toward greater integration. What holds these countries together?

The answer is discontent with the policies of the traditional global leaders.

It became obvious during last year’s BRICS summit in China that BRICS did not share the West’s prevalent enthusiasm about the “Arab spring” and saw trouble ahead. At the very moment when Washington, Brussels and other European capitals were applauding the toppling of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and encouraging insurgents in Libya, BRICS threw a bucket of cold water onto the celebration. The five BRICS’ leaders, one of whom, South Africa’s Jacob Zuma, led the African Union’s effort to achieve a negotiated settlement between Libyan strongman Moammar Gaddafi and his enemies, expressed “deep concern” about the developments in North Africa.

The continuing war of militias in Libya, troublesome developments in Egypt – including anti-Christian pogroms and tensions between the Islamists and the military – have all proven at least some of the BRICS’ concerns to be reasonable.

In terms of foreign policy, it is the West’s interventionism that pulls these different nations together, cementing the BRICS better than the old leftist illusions, which were in some form present in all of these countries during the 20th century. Alas, the West’s interventionism is not limited to such cases as Libya or Syria. Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff recently expressed dismay over Washington’s currency policy, which devalues the dollar and makes the ability of Brazil and other developing countries to export to the U.S. extremely limited. The response was a cold shoulder turned to Rousseff during her recent visit to Washington.

Adding insult to injury was U.S. President Barack Obama’s refusal to review the very possibility of lifting the economic blockade of Cuba – voiced during the recent Summit of the Americas in Cartagena, Colombia, which provoked outrage not only in Brazil, but just about in all Latin American countries. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos had to make a special trip to Havana to smooth things over with Cuban leader Raul Castro.

Does this mean that Brazil, Russia, India, China ad South Africa do not want democracy for Cuba or Syria? Of course they do; they are no less humanist than the Western powers. However, the BRICS countries do not want democracy we to be “exported” by military interventions or payoffs to the opposition in these countries. That is why the disparate BRICS countries have found each other to be real friends – they have a need.

Babich is a political analyst at the Voice of Russia radio station.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox