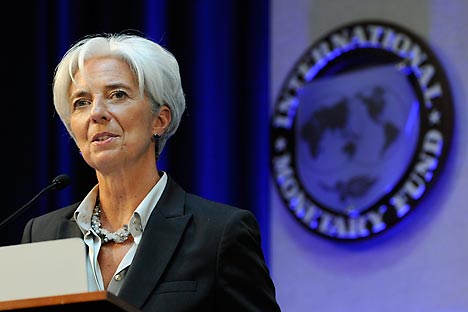

IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde delivers remarks at a Banque de France panel on financial stability review during the semi-annual meetings of the IMF and the World Bank in Washington, April 21, 2012 Source: Reuters

The IMF says it has new funding totalling $430bln. The fund’s strategic pocket is designed to help the global economy but it’s naturally a “air bag” for the Eurozone countries which have pledged $200 billion. In a joint statement after the meeting in Washington, the IMF, the G20 finance ministers and Central Bank governors said: “There are firm commitments to increase resources made available to the IMF by over $400bln in addition to the quota increase under the 2010 reform.”

The US has adamantly said it has no plans to increase its share in the fund in this politically tough year for the country. Canada is also keeping aside, saying it will rather save the money for its own rainy day, and solve their financial problems using the county’s own resources, rather than hope to get the money back in the form of emergency assistance if the crisis worsens. With 2 major players refusing to chip in, the IMF’s Managing Director Christine Lagarde welcomed Japan’s generous injection of $60bln which is the biggest contribution from a country so far. Other countries contributing significant amounts include Australia $7bln, Singapore $4bn and South Korea $15bln.

With the crisis in Greece and an emerging meltdown in Spain, the IMF is likely to come under increasing pressure to support broken economies with supersized bailout packages.

The BRICS are also pledging support but keeping their amounts secret until approved at home. Five of the world's fastest-growing economies Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa said they will contribute at least $72bln to the IMF to help protect the global economy from Europe's deepening debt crisis. However, the BRICS have promised to announce each of their contributions at a June summit of the Group of 20 leading economies as they are using it as a lever to get greater say in the IMF.

Vladimir Rozhankovsky from investment group Nord Capital says “not that the BRICS would go back on their promise to give the money, but they can be intentionally slow in handing over the funds, citing technical reasons for the delay”.

Analyst Johan Van Overtveldt sounds more adamant. “These are all just private pledges rather than real commitments. There’s a very long way to go before the money is put on the table. In fact nothing has gone beyond discussions and with no real actions taken place. So there can only be talking of securing $360bln, the money which has been mostly committed by European nations and Japan”, he maintains. “Nations such as Russia, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand are still considering chipping in money. It’s not right to say that the IMF has $360bln in its pocket until the money is on the table. “Getting an approval at home” looks like an excuse which will give the BRICS more time to see how the situation evolves. What they are really at and what would make them be more “decisive” is getting more rights”.

Hoping to put an end to the long quest for money to boost IMF’s financial strength, Christine Lagarde is now facing a serious challenge of finding a way to give emerging economies the influence they are asking for in return for the money, and at the same time do not upset or turn away the Fund’s dominant powers – the US and Europe.

Many analysts are now saying the IMF has found itself in a very ambiguous position – since it is desperate for money and with some of the major powers refusing to increase their financing, the fund has no choice but to agree to the BRICS demands for a greater say. Simultaneously, the situation emerges as the number one chance for the BRICS and other emerging economies.

Now Europe has to yield something in return, and the fund’s pledges that the strategic money stockpile will make the non-European members immune to the Euro zone crisis spill-over is not enough. The emerging economies want to hear from the G20 that they will be rewarded over time with more IMF voting power through an increase in their so-called membership quotas, an issue that is central to keeping them engaged in the IMF.

Economics writer Johan Van Overtveldt warns changes are not quick to come. “There’s no talk right now to change the voting rights in accordance to the amount of money injections each country makes. Currently European countries enjoy 22.5% of the voting rights, and the US has about 16%. There’s a huge discrepancy in how the voting rights are distributed – for example such big economy like China has 4%, and a much smaller Belgium has roughly half the Chinese at 1.8%. And there has been no clear agreement or compromise as yet over how these rights will change in the future. Of course changes are inevitable, but we need to make the time framework clear. We have a very long way to go”, maintains Johan Van Overtveldt.

To stick to her promise to the emerging nations, Lagarde will need to be seen to be pressing the United States to pass the reforms which will change the current quota system.

Vladimir Rozhankovsky claims Lagarde does not have the authority to promise anything like that. “She’s not in power to distribute voting rights. She is engaged in searching for money and making sure it is invested properly. Voting rights distribution is a collective decision, with all of the fund’s members giving the green light to the reforms for them to be pushed through.”

The current quota system follows the logic of a shareholder-controlled organization: rich countries have more say in the making and revising of rules. Since decision making at the IMF reflects each member’s relative economic standing in the world, wealthier countries that provide more money to the fund have more influence in the IMF than poorer members that contribute less. Emerging economies represent a large portion of the global economic system but this is not reflected in the IMF's decision making process through the nature of the quota system.

Canada and the US have confirmed they are not planning to increase their share in the fund.

Simultaneously, according to Johan Van Overtveldt “the US is absolutely not prepared to give in on any part of the voting rights.” “The current standing cannot be changed quickly and without pain. It’s more likely the European nations will give up their rights, particularly in the situation when they turn out to be most affected by the crisis. The US will fight for their rights especially ahead of the presidential election in the country where US President Obama may face re-election”.

Vladimir Rozhankovsky agrees that the US will not share their rights with BRICS easily, however he says at the moment the US have no reason to be nervous. “The US knows the changes will not be quick, and it’s by no means they can come any time before the US election. So America realises, so far it will not lose any rights because of not lending financial support to the IMF. On the other hand, in the long-term perspective, if the reforms take place, the US will have no choice but to give up some of their voting rights if needed as they will not let euro zone fail.”

On April 21, the IMF called for the 2010 voting reforms to be ratified "expeditiously." But emerging countries say those changes do not go far enough and bolder steps are needed. A fresh set of negotiations has already begun.

“Christine Lagarde realizes the current distribution of powers is wrong. If the US doesn’t agree to cede some of their rights to emerging nations, Lagarde will have to either take those rights from European countries, or the non-European nations will not give the money she needs. And this situation will be utterly unfavourable for Lagarde, with the IMF being unable to support the euro zone in a way it used to do that in the past. So she will have to confront a challenge of finding a compromise. And the ideal solution might be to distribute the rights according to the amount of fresh money the countries put on the table”, believes Johan Van Overtveldt.

Europe's overwhelming dominance of the board has become a particularly sensitive issue because the IMF has been called upon to lend to crisis-struck euro zone nations. Non-euro zone nations and especially non-European are looking for an incentive to cash in. The Fund has always been run by a European. And the IMF will also need to make sure Europe sticks with a commitment to reduce its over-representation on the IMF board by giving their votes to emerging and developing countries.

Vladimir Rozhankovsky though says the BRICS problem lies in its member-countries inability to cooperate efficiently. “The BRICS countries need to find a way to solve their problems by themselves. Before, they used the US or other countries as mediators in the negotiating process. Now they have to act on their own. Their need to take it into their own hands, setting up an alliance with a headquarters, the BRICS own elected chief who can speak for the union expressing its communal decisions and push them through to Europe and the US. At the same time, not only the BRICS need time to mature, but the Old World itself needs time to realize that changes are imminent.”

First published in RT.com

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox