What Russians think about Stalin

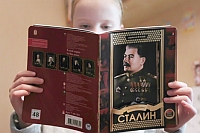

Some older communists still revere Stalin and use his image at their protests. Source: AFP / East News

Moscow

history teacher Stephan Bochkarev often recalls a lesson he taught his students

several years ago. It was a lesson about Joseph Stalin that he happened to be

teaching on the day the director of his school decided to observe his class.

“I went strictly by the book, talking

about the repression, when the director interrupted me and stopped the lesson,”

he recalled. “She really did not like the fact that Stalin was presented in a

negative light.” Bochkarev, who now works for a private school in Moscow, said his lesson

caused a scandal at the school and he subsequently resigned.

Sixty years after Stalin’s death, he is still cursed, worshipped, and monetized

in Russia.

Communist Party members march under his image and tourists get their photos

taken with Stalin look-alikes on the pedestrian streets. Yet what happened to

Bochkarev is becoming less common—and less acceptable.

The percentage of Russians with a positive attitude toward the Soviet leader is

30 percent today, according to a Levada

Center study.

Asked whether they would like to live under Stalin now, only 3 percent said

yes.

The perception outside Russia

is that society is split into Stalinists and anti-Stalinists. But this is

outdated, according to sociologists. A majority of Russians, 60 percent in

fact, have two seemingly incompatible images of Stalin in their minds: the

cruel tyrant who murdered millions of people and the wise statesman who led the

Soviet Union to prosperity.

In the West, Stalin is best remembered for his forced collectivization of farming,

which led to famine and millions of deaths, and the Great Terror, during which

thousands were executed and millions more sent to the Gulag for long terms of

slave labor. In Russia,

his memory is more complex. For some, he is inextricable from the victory over

fascism.

In Russian society, there is no rational understanding of Stalin’s role, said

Boris Dubin, head of sociopolitical research at Moscow’s

Levada Center. Any focus on the achievements of

the U.S.S.R. under Stalin is interpreted as an attempt to justify his crimes,

while putting the emphasis on the terror of his crimes upsets Russians who want

to be proud of their past.

This duality can be seen in today’s classrooms, where opinions are changing

slowly, even if history textbooks published in the last few years tend to

ignore Stalin’s crimes.

“From my nearly 15 years of teaching, I have the impression that Stalin is the central figure in Russian history of the 20th century in the eyes of the vast majority of students,” Bochkarev said. “And, often, this image basks in an aura of heroic grandeur.”

At the request of RBTH, Bochkarev asked his students to write essays about

Stalin to express their thoughts. He requested that RBTH use first names only.

“I think that Stalin’s terror will be imprinted on people’s minds for a long

time,” said student Eugene. “And even now you can hear its echo in the position

‘I do not care about what does not concern me directly.’ Stalin is often spoken

about in a half-bad, half-good light.”

When discussing Stalin’s popularity, sociologists refer to the “Stalin myth,” which reflects more of a generic heroic symbol of the Soviet people rather than a specific historical figure, Dubin said.

This myth was cultivated in the 1960s and 1970s, when Russian were even more divided,

according to Boris Drozdov, 78. Drozdov’s father was sent to a prison camp and

his grandfather was executed. “Those who were unaffected by the repression

thought of Stalin as a genius,” he said. “But those run down by the repression

machine believed that he personified evil.”

The pain of memory was so intense that amnesia has been a favorite response,

according to sociologists. “This happened by way of erasing the memory of the

repressive nature of the totalitarian regime, mass murder, gulags, deportation

of entire nationalities,” said Dubin.

“In Russia, the memory of the terror has been driven to a far corner, not least

because there are no monuments, no memorial plaques, no museums – there is

nothing,” added Arseny Roginsky, who heads the Memorial Historical Society,

which aims at rehabilitating the victims of political terror.

Memorial notes that people are much more interested in their relatives, who

died as victims of political repression, than they were in the 1990s. In recent

years, the number of people visiting Memorial in search of relatives who

disappeared during Stalin’s purges has been growing. About 1,000 people come to

Memorial each year, he said, a dramatic increase from the 1990s.

The most recent official effort to deal with the issue of Stalin’s crimes took

place in 2011 under President Dmitry Medvedev. “This is essentially an attempt

to perpetuate the memory of the victims of political repression rather than a

de-Stalinization crusade,” said Mikhail Fedotov, head of the Presidential Human

Rights Council, which initiated the campaign.

The Human Rights Council supports the establishment of memorials to the victims of repression in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The council also proposed creating a National Institute of Memory.

Fedotov noted that if Medvedev is appointed prime minister to Putin’s

president, the program will continue, though now government officials have

slowed the process until the new presidential administration is in place.

Roginsky said he was skeptical about the program, since many archives are still

kept secret and not open to the public.

As for history teacher Mark Bochkarev, he feels free to discuss Stalin in a private school, “where children have a fairly high level of knowledge,” he said. “However,” he mused, “even they sometimes employ the image of ‘Stalin-creator’ rather than “Stalin-destroyer.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox