In the depths of the Siberian taiga, on the bank of the river Yenisei stands the closed city of Zheleznogorsk, surrounded by a barbed wire fence. You can’t just go and live there if you want to, and the local residents are only allowed to travel home if they have a pass, and even then they have to undergo a full check first.

Once inside the city, it’s like travelling back in time to the USSR of the 1950s and 1960s: there are wide avenues flanked by five-storey blocks of flats painted in different colours. In the centre stands the Rodina [Motherland] cinema, which was a typical feature of all small provincial cities in the USSR, and the main entrance to the factory which before the days of perestroika built the famous Kosmos and Molniya satellites, the most powerful of their time. After the slump of the perestroika period, at the beginning of the 21st century the city and its industry gained a new lease of life, thanks largely to the programme to develop the GLONASS navigation system. Zheleznogorsk once again became a magnet for young specialists.

Soviet romanticism

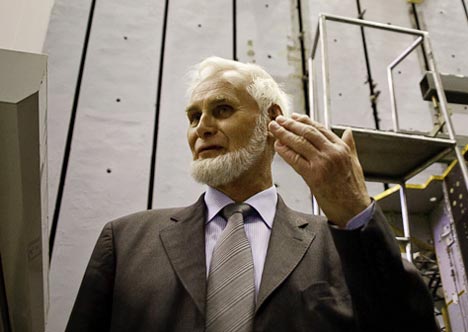

“In the 1960s the whole USSR dreamed of space! It was an honour to work in industry,” says Vladimir Khalimanovich, director of the Industry Centre of the M.F. Reshetnev Information Satellite Systems company (ISS). He came to Zheleznogorsk 47 years ago from Kazan, where he had graduated from the Academician A.N. Tupolev Aviation Institute. At that time, every other student dreamed of a place like this, because only the best and the brightest were recruited to closed cities, where secret military establishments were usually located.

Solar wings: A $200 million gamble

It costs approximately $150 million dollars to build one satellite, plus $50 million– the launch cost plus 20% – for insurance. One small error means blowing up millions of dollars into space, literally. A huge number of tests are, therefore, done at each stage of construction. One of the most spectacular is the trial unfurling of the wings, i.e. the solar batteries of the finished satellite. “The preparations can take several days. Operations begin only when the staff have checked everything ten times and put loads of signatures on various documents and the client’s representatives have switched on their video cameras for the minutes,” Sergei Apenko, chief designer for electrical testing and electrical design, says jokingly. And so the system is launched. The folded solar batteries begin very slowly to unfurl. For about 15 seconds, specialists and the assembly room staff who have gathered to gape stand there, holding their breath as unfurling the wings is a very complex task – it takes only one small mistake to turn the satellite into a useless piece of space junk.

Life in such a city meant living with a few restrictions: if you wanted to invite relatives or friends to visit, you had to get special permission from the security service. “That procedure applies today too. At first it’s inconvenient to have to ask permission every time, but you soon get used to it,” says Yelena Prosvirina, an engineer at the factory. She moved to Zheleznogorsk from Omsk on the eve of perestroika. But the plus points outweighed all the inconveniences: for example, Zheleznogorsk received centralised supplies of various goods which it was impossible to obtain in ordinary cities in the USSR.

In the 1990s, the city fell on hard times. The centralised supplies of foodstuffs ceased, and people were plunged literally overnight into brutal realities of capitalism. Like the majority of Russian enterprises, ISS, around which the city’s life revolved, lost the lion’s share of its financing. The days of stagnation began. The factory continued quietly building satellites for military purposes and improved the Uragan navigation system, the forerunner of the modern GLONASS. But there was a sharp brake on development, and the factory’s workforce of more than 8,000 people was almost halved. This triggered an exodus to big cities in search of better living conditions.

The engineers were only able to breathe easily at the start of the new century, when the government began to invest funds in the creation of the GLONASS satellite navigation system as part of the space programme. A year ago the system’s 24 satellites were brought into full operation and now they offer competition to the American GPS. The state provides two-thirds of the 20 billion roubles that make up ISS’s annual turnover, with the rest coming from commercial orders.

The realities of capitalism

It would all have been fine, but the ISS was so caught up with its internal issues that it missed an important moment at the end of the last century when satellites became an important commodity in the global market. The Russians were therefore almost 20 years behind and effectively out of the game, and the Americans took over the lead in the sector, once considered the forte of the Soviet Union. It was only in 2008 that the ISS started getting international orders. First, the Israeli operator Space-Communication Ltd ordered the AMOS-5 satellite, then in 2009 the Indonesian company PT Telekomunikasi Indonesia Tbk bought the Telcom-3 telecommunications system, and later contracts were signed with Ukraine and Kazakhstan. “Every year we take part in four or five tenders, of which we win one. One international contract per year is enough for us. That’s all we can handle at the moment,” says Vladimir Khalimanovich. Today about 40 satellites are in production at the same time, including secret military systems, Glonass satellites, and telecommunications and geodesy satellites for Russian operators –the Russian Satellite Communications Company, the federal state unitary enterprise and Gazprom Space Systems.

The sharp increase in orders has restored the organisation’s staff numbers to their previous level. In 2005 there were 5,000 people working at the ISS, but now there are 8,500. Moreover, most of them are young. Graduates from the aviation universities in Kazan, Tomsk and even Moscow are again being drawn to Zheleznogorsk, but this time it’s not romanticism that’s attracting them but money. The fact is that the pay here for an engineer just starting out is $1,000, while on an average across Russia a graduate from a technical university can only hope to earn half that much. Incidentally, the ISS has retained the original Soviet training system for young specialists. After their fourth year in an institute, students come to the company and work for two years in various roles and gain experience (while getting full pay), and only after that do they defend their diploma. “ISS is an excellent place for training staff. If we could, we would buy up the majority of its specialists,” a manager of a Moscow company linked with satellite construction told RIR.

We’re still a long way from the former abundance, but the emergence of “new blood” has started to breathe new life into Zheleznogorsk. A new housing estate has been built, where employees of the factory can buy a flat through a preferential mortgage system. “The company covers half the interest,” says ISS staff member Kristina Uspenskaya. But the services in the city are still not developed. For a 100,000-strong population (including residents of the surrounding villages, who are allowed access to the city), there are just handful of cafés, a restaurant, a single night club and a cinema where the price of a ticket is comparable with those in Moscow – from 300 roubles. “It’s difficult to start a business in a closed city. The process requires stacks of agreements. Therefore there’s no competition,” explains Kristina. The young woman says that every week she and her husband get in their car and drive 60 kilometres to Krasnoyarsk so they can take a break and buy some food – it’s a lot cheaper there.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox