Drawing by Niyaz Karim

Under the chairmanship of Boris Yeltsin, it also announced that the Russian republic intended to constitute itself as a member of the “reformed” U.S.S.R. More crucially, it established priority of the constitution and laws of the Russian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic (RSFSR) over the legislation of the Soviet Union.

This was a blow from which the Soviet state never recovered.

The day was established as a national holiday in 1992, when the U.S.S.R. was no more and Boris Yeltsin was the president of the independent Russian Federation. Today, it is the main state holiday, which is supposed to mark the foundation of a modern democratic Russian state. A lavish reception in the Kremlin accompanies it. However ordinary Russians remain indifferent or, in the case of the older ones, are outright hostile toward the holiday. Many still call it, semi-ironically, “Independence Day” – and usually add a bitter question: “Independence from whom?”

For the peoples of Central and Eastern Europe shedding the Communist skin meant, first and foremost of all, liberation from a foreign occupation. Even such countries as Romania and Bulgaria, which by 1989 haven’t had the Soviet garrisons on their territories, could reasonably argue that their troubles were the logical result of the 1945 Yalta agreements between Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill and the loss of freedom that came with them.

Not so for the Russians. Looking back at the events of 1989 to 1991, I contemplate how much was accomplished then by relatively few people. Several hundred thousand in Moscow and Saint Petersburg (which only got its historic name in 1991), the restive Baltic peoples and some Georgian nationalists drove the Communist state into the ground. The system was already fatally weakened by economic inefficiency and undermined by external circumstances like the war in Afghanistan. Still the speed and relative peacefulness of its disintegration (at least compared to Yugoslavia’s bloodbath) was akin to a miracle. But there was a flip side to this: The Russians were unprepared for the loss of what, for better or for worse, they came to consider “their” country.

The U.S.S.R. was the world’s last great land empire to disappear. The former “colonies” never went away. They sit right across what many consider to be artificial borders. The Russians are largely indifferent to leaving the mainly Muslim Central Asia and the restive Caucasus behind. But when it comes to Ukraine and Belarus the feeling is that these are some relatives who wandered off but will eventually come back into the Russian fold.

The imperial nostalgia was exacerbated by domestic developments. After a brief period in the early 1990s when perestroika-era intellectuals played leading roles in the Yeltsin government, the Soviet-era bureacracy took over again, bringing along with it an outdated view of governance, Soviet-style phobias and unbound cynicism multiplied with greed, which was now given an official sanction under the banner of capitalism.

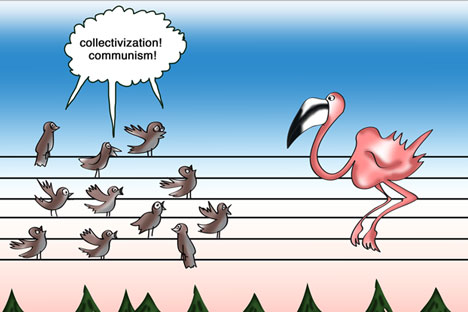

Recently I made a presentation at a political science seminar in the southern Russian city of Krasnodar, one of the most prosperous in the country. Among a large group of 20 to 25-year olds there were quite a few who still insisted on the need “to keep the best from the Soviet legacy.” They were at a loss, when I asked them to describe what should be kept. Some started talking about collectivism that stood in stark contrast to consumerism and individualism of the modern age. But when I asked whether they accepted that the price of this collectivism was the Russian Civil War, the Gulag and the permanent lack of basic liberties, it gave them pause. To me it was the best proof that Russia’s political class has until now failed to redefine the national identity in a forward looking, modern way.

This has to change. The students asked me about the recent wave of pro-democracy protests in Moscow; they felt that change was needed but were in the dark about whether it is achievable. I think once again it falls on Moscow and Saint Petersburg to lead the movement for Russian renewal. Only if (or rather, when) it succeeds, will the derided declaration be vindicated.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox