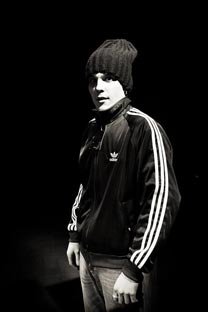

Talgat Batalov in “Uzbek”

Early in Talgat Batalov's self-directed, self-acted production of "Uzbek," the performer begins handing out passports and military service records for the audience to look at.

"Don't forget to give those back to me," he says with a small laugh. "I still need them."

"Uzbek" is more than theater or less than it, depending on your point of view. Like many performances and events at Georg Genoux's Joseph Beuys Theater, it is definitely a foray into social commentary.

In recent years, as political developments have grown increasingly complicated in Central Asia, Moscow has become a destination of choice for displaced persons from Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Like many immigrants from Africa or Eastern Europe to Western Europe, or Mexico and the Philippines to the United States, these refugees have sometimes found themselves in a serious bind. They are underappreciated — to put it lightly — by the local population. They are easy targets for corrupt policemen and city officials. They generally wind up doing the dirtiest and lowliest work that any city can throw at a population.

Batalov is the perfect individual to tell the story of at least a few of these immigrants since he is one himself. He was a member of the company of Mark Weil's Ilkhom Theater in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, when that world-renowned director was murdered outside his apartment in 2007. That was sign enough for Batalov that he no longer wanted to hang around and see how events would develop in Tashkent. He headed for Moscow almost immediately.

Working with playwright Yekaterina Bondarenko, Batalov in "Uzbek" mixes the stories of several immigrants in Moscow with his own. But his own story shows how mixed up these things can be.

"In Uzbekistan I was considered a Russian," he tells the audience. "But here I am an Uzbek." The irony thickens when he explains that there are 160 different nationalities living in Tashkent and, actually, by nationality, he is a Tatar. His family ended up in Uzbekistan because of mass evacuations that took place during World War II.

Batalov seats the spectators in a circle in the middle of the hall at the Joseph Beuys Theater and walks around them, stopping in various places from time to time to add new details and introduce new characters into his narrative.

"I'll tell you this," he says after handing his military service booklet to a spectator in the first row, "You feel just as bad in a Russian draft board office as you do in Uzbekistan."

The actor's delivery is folksy and low key. He tells the first-person tale of an Uzbek immigrant who works in an open-air market. He reads a handwritten letter that his father once sent him, and relates some advice that his mother once gave him over Skype. He steps into the midst of the spectators and delivers a speech by Vladimir Putin on Russia's tradition of being a multinational state since the 18th century. This is followed by a vignette of Batalov finally receiving his Russian citizenship.

"Why are your hands so sweaty?" the woman handing him his documents squeamishly asked.

"It's not every day I receive Russian citizenship," was Batalov's loaded, deadpan answer.

Batalov doesn't take sides in "Uzbek." Almost everything he utters cuts two ways. Consider this, for example: He says everyone in Uzbekistan thinks there are gun battles on Moscow's streets all day long "because everybody in Uzbekistan watches only Russian television. Uzbek television is completely unwatchable."

Or consider this short exchange from an interview he did with a police sergeant in Moscow. "Of all the people I have apprehended," the policeman told him, "Tajiks, Kyrgyzes, Uzbeks and such, the biggest cowards are Uzbeks."

It's probably true, Batalov confirms. Cowardice was "instilled in them by the Uzbek government."

Talgat Batalov's "Uzbek" is a brief but poignant stroll through some of the dangers, paradoxes, humor and nonsense that a person in the 21st century encounters when he or she demonstrates the hubris it takes to abandon one culture and take on another. Whether this is theater or whether it is primarily social activism in theatrical guise, it is a testament to human resilience as well as to the hostilities that most governments foster in regards to the individual.

"Uzbek" plays Mon. and Tues. at 8 p.m. at the Joseph Beuys Theater, located in the Sakharov Center at 57 Zemlyanoi Val, Bldg. 6. Metro Kurskaya. Tel. 8-967-176-5705. www.beuystheater.ru. Running time: 1 hour.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox