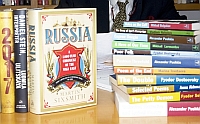

Telling Russian stories in English

Source: AFP / East News

Antonina W. Bouis, renowned translator of more than 50 books from Russian into English, calls her profession “the most vital and underappreciated art” and the translator’s function that of a “telephone” – ideally unobtrusive, and often taken for granted.

|

| Antonina W. Bouis. Source: Press Photo |

Bouis’s memorable introduction to, “Read Russia, An Anthology of New Voices,” makes the point that “you wouldn’t be reading these stories without their translators.” As much as new Russian fiction unveils significant Russian writers, it also showcases the best translators, from Andrew Bromfeld and Arch Tait to Marian Schwartz.

Many readers don’t fully appreciate the art of translation. “When you translate a book, you basically “write” a book,” Bouis said in an interview in Manhattan, where she lives. “Of course, there’s an outline you’re supposed to stick to – but it makes it a whole lot easier. It’s more of a puzzle, and interesting in that way – to be forced to remain within the confines of the given project. Also, every author has to sound different; they can’t all sound like Bouis.”

While the majority of her translations have been of contemporary writers, she has done a few classics; last year she translated Mikhail Bulgakov’s “A Dog’s Heart,” the third translation of that work. “That’s the thing about classics – they need to be retranslated every generation. Translations age – and I guess that’s proof of their artificiality. The original remains. You don’t want Tolstoy to sound contemporary, but you do want the translation to sound not old fashioned and weird,” she said. “And there’s the fine line – because you’re interpreting the text for a contemporary audience and you have to decide if you are going to add footnotes, or slip in little additional phrases, or write a foreword.”

Bouis is Russian American. Her parents met in a displaced persons camp outside Munich, Germany in 1945 before moving to the U.S. when she was four.

She grew up as an American, she said, although Russian was spoken at home and she was sent to a Russian school on Saturdays. Another Russian aspect of her childhood was the fact that her parents insisted on their daughter being fluent in French and that she take piano and ballet lessons like a baryshnya, a proper young lady. All that stood her in good stead later on. Even her French was useful – she married a Frenchman, Jean-Claude Bouis. In the late 1980s, she worked for George Soros, helping him set up his foundation in the Soviet Union during perestroika. It was a “heady experience,” she said, meeting so many people and participating in life-changing events.

As one of the most experienced and well-respected translators, Bouis has her pet peeves. One of them is the fact that Russian officials (among many other foreign dignitaries) bring their own interpreters to the United States and have them interpret into English. While it is understandable that Russians feel more comfortable with a Russian interpreter they know than a local, the end result is never as good, she said. The best result is the method they use for heads of state at top-level conferences – a native English speaker interpreting from Russian to English, and a Russian interpreter to do the opposite, as well as keep an ear on the local interpreter to make sure he or she is being accurate.

Translation's Catch 22

Interpreting and translating can be a Catch-22, she mused. Usually one is hired by someone who cannot judge the quality of your work because if he really knew the other language well enough to be a good judge, he wouldn’t need to hire a translator in the first place.

Bouis came across such frustrations as a young translator when she was not well established enough to pick and choose her projects, and she sometimes had to work with difficult authors. Once she translated a book by a young Russian author who thought his English was excellent. “He would question almost everything – and of course it was more than tiresome.” The author looked over her shoulder all the time, nitpicking and pointing out words he looked up in a dictionary, regardless of context or common usage. She’d never take on such a project again, she swore. “The more professional a writer is, the more that writer has been translated into other languages, and the more he or she is willing to say ‘do what you need to make me sound good in English, that’s your job.’ And they leave you alone, because they trust you. But I’m always grateful to living authors, because I can ask questions and get feedback.”

“Americans in general tend to treat literature very pragmatically,” she explained. “We think, ‘what am I going to learn from it? I’m going to spend all this time reading a book, so what am I going to learn?’ America has always been very self-sufficient – culturally, it’s isolated.” It is a big country with plenty to do and see within, so there isn’t that big an interest in what’s beyond its borders, she says. “In the Soviet period, Russians read more than anybody else, because a) there was nothing else to do, and b) they were all dying to know what was going on in the outside world – and that’s something Americans never lacked access to.”

Translation was such a highly valued skill in the Soviet Union because translators were windows to the outside world ordinary citizens had no access to. “Russian translators were really spoiled in the Soviet times,” Bouis remarked. “They were stars – if you were a translator, it was a great thing – you weren’t just some little telephone.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox