Russia faces competition in space

The workhorses making to $700-800 million a year for the Russian space industry are the Proton and Soyuz carriers, which were developed during the Soviet era. Source: AP.

Delivering a couple of tons of cargo into near-earth orbit is a lucrative business. Many countries wish to have useful hardware in orbit – including communication, navigation and surveillance satellites – and they are willing to pay for it. Additionally, few countries can make such deliveries, which affects the pricing for the service.

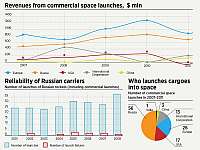

Russia has been the leader in the global market for commercial space launches due to a careful cost-benefit analysis. Russia charges less for a launch than its competitors (some $10,000-12,000 per kilogram of cargo delivered into orbit, compared to about $20,000 charged by its American and European competitors), and until recently, had a success rate of near 100 percent. The workhorses making to $700-800 million a year for the Russian space industry are the Proton and Soyuz carriers, which were developed during the Soviet era. These rockets may have been old, but they have proven reliable. Until recently.

Failed launches in the last 18-24 months have increased risks for customers’ risks, while competitors from China, India and Japan have become more active. Many are already capable of offering very attractive rates similar to the Russian ones.

New rivals

About a decade ago, Russia competed only with EU and the U.S. for commercial space launches, and the United States did not actively pursue commercial launches, reserving its carries for exclusive use by the U.S. space program.

Over the past few years, however, the market has witnessed dramatic changes. In the space of only five years, China, which engaged Russian companies to deliver its cargoes into orbit for years, not only started delivering its own cargo, but also launching satellites for other countries. China made its debut launch in 2007 and in the first half of 2012 became the world’s leading nation in the number of launches, with 10 launches of its Long March carrier rocket. During the same period, Russia made nine launches and the United States made eight. China also offers very competitive prices.

The competition for commercial space launches became even fiercer this May, when the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries announced a successful launch of a South Korean satellite by an H-2A launch vehicle. If Korea had opted for Russian services to take its satellite into orbit, it would probably have paid half as much, but the Koreans said they chose the Japanese rocket because of its reliability: the H-2A has been launched 21 times during the last 11 years with only a single failure. The top executives of the Japanese company have already said that that the company was looking to take away market shares from Russian and European carriers.

Apart from China and Japan, space programs are actively promoted in India and Brazil. But Russian experts have doubts that these two countries have the technology to compete with Russia. Yet the fact remains: India has its own carrier rockets, meaning that it can at least launch its own satellites. Brazil is also on its way on to the market. They may not compete with Russia for external business, but they will take their own business away from Russian launch firms.

The threat of private business

In late May, the American company SpaceX sent its Dragon spacecraft to the International Space Station (ISS). The Dragon become the first private ship unaided by state agencies to reach the ISS and return to Earth. Another firm, Orbital Sciences, plans to launch its cargo vehicle, the Cygnus, to the ISS within six months. These developments indicate that a new era is beginning in space transportation, one in which private business will compete with public entities for launches.

So far, American companies have focused on serving NASA, which is why Edward Crawley, and expert on the U.S. space program, said in a recent interview that neither the Dragon nor the Cygnus would be able to compete with Russian carriers at the moment. “I don’t think that private companies will change things on the market for space launches. Russia has a proven range of carrier rockets offering the benefit of cheap launch fees. Even cheaper U.S. spacecraft won’t be able to compete with Russian craft as far as price is concerned. Russian producers should focus on competing with Chinese and Indian makers, which offer even cheaper launches,” Crawley said.

Still, eventually private space companies will eventually become serious competitors. The laws of the market state that private firms will become increasingly efficient but cost less.

The Japanese H-2A launch vehicle was also developed by a private corporation. Although the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency started the project, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries took over in 2007, when the Japanese space industry was privatized. The corporation’s entry onto the international market for space flights is attributed to the fact that Mitsubishi felt it was not making enough from orders from the state.

Breathing room

Russia is in need of new bargaining chips, and the Angara space-launch vehicle, powered by an eco-friendly oxygen-kerosene engine, might become one. The Angara, which is expected to replace the Proton, is currently under development by the Moscow-based Khrunichev Research and Production Center. However, the new rocket has not made its debut and the announced deadline has been shifted repeatedly; it is now expected to be completed sometime in 2013.

Despite these challenges, there is no real cause for concern at the moment. Commercial launches account for only 2 percent of the market. There are three key segments on the market for space services: communications (GPS, satellite broadcasting and telecoms), research and remote sensing. Russia is actively engaged in some of these segments, but in others it plays second or perhaps even third fiddle.

Incidentally, the Curiosity Mars rover, which has recently been in the news recently, was delivered into orbit by the Atlas V booster, which uses the Russian RD-180 rocket engine. Russia is not gaining any substantial profits from the project, though: it is a common opinion in the media that Russian engines are sold at dumping prices. From the point of view of the international division of labor, Russia plays the part of a country with low-paid manpower. This is better than nothing, but not something to wish for.

This article has been abridged from the original Russian version, which is available in Russian in Russian Reporter Magazine.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox