Russia needs to modernize its nationalities policy

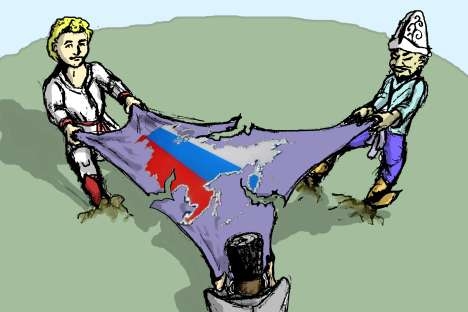

Drawing by Dan Pototsky

The “nationalities issue” has in recent months become the focus of renewed media attention. Adding fuel to the fire is the fact that the discussion focuses on the Northern Caucasus, Russia’s most turbulent and unpredictable region.

Other tell-tale signs are the conflict between the Chechen and Ingush leaders over the borders between the two republics; the murder of one of the spiritual leaders of Russian Muslims, Sheik Said-Afandi; and the statement by Krasnodar Region Governor Alexander Tkachev on the need to create Cossack patrols to protect the region from people from the Caucasus.

The latter initiative seems to be an attempt to set different groups of citizens against one another, since the governor was not referring to illegal immigration into Russia. Instead, Tkachev spoke of putting up barriers for Russians living in the North Caucasus — an inseparable part of modern Russia.

Indeed, it is high time that we stopped glossing over the nationalities question.

To begin with, any diverse society potentially faces the threat of ethnic strife and separatism. This goes for affluent and prosperous countries as well: Just look at some European and North American countries such as Spain, Belgium, Britain, France and Canada.

However, for Russia, the experience of the United States is arguably the most interesting. The racial unrest of 1968 (in the wake of the assassination of African-American leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.) threatened to split the country apart. Today, four decades later, the problem no longer looks political, but merely social. The country has reached a higher level of integration, with African-Americans achieving prestigious positions as president, secretaries of state, four-star generals, media stars and sports idols.

In Russia, the increasingly frequent, racially-motivated incidents occurring by the day need not be interpreted as signs of the country’s impending collapse. There is hope for the future. What is needed above all is a modernization of nationalities policy, along with its symbols and sociopolitical vocabulary. Failing that, the vacuum will be filled by various national projects in which there will be no place for Russia as the state for all Russians (regardless of their ethnic affiliation).

Unfortunately, Russia’s nationalities policy has been concerned with folklore and ethnographic matters for far too long. It is significant that even the Ministry of Nationalities has been shut down; authorities claimed that they could not find a relevant use for it. Nationalities policy was often reduced to a set of measures aimed at giving preference to ethnic groups or determining the “indigenous” peoples to which other peoples on a certain territory had to defer. These attitudes were characteristic not only of fringe elements and extremists, but of representatives in the ruling party who proposed strengthening the practice of “registration” and restrictions for newcomers, including fellow citizens from other regions.

As a result, relations were built up not with an individual or citizen, but with the ethnic group seen as a “collective person.” This contributed to the fragmentation of Russian society. Experts understand that “fencing off” is not an option in response to these divisions — objective economic, geographic and demographic laws prevent this. If the population in the North Caucasus grows and Chechnya, Dagestan and Ingushetia find themselves without enough land of their own, then labor migration could not be stopped by any barriers. Moreover, this migration is socially desirable as a kind of preventative measure. The Caucasus “cauldron” is much more likely to blow up without internal migration.

Consequently, we should not be thinking about how we can get “good Russians” or “good people from the Caucasus” on one side. Instead, we should be thinking about how to foster loyalty to the Russian state and society, not only among various ethnic groups, but also among various social and economic groups. A new nationalities policy should center on the idea of a “civil nation” that emphasizes political identity, rather than one based on ethnicity.

There are tentative signs that the situation may change. The first meeting of the Presidential Council for Inter-Ethnic Relations was held in Saransk in August 2012, and it was attended by a number of well-respected academics. The meeting was set to the task of working out new conceptual principles for Russian policy in this delicate sphere.

Addressing the Council, Valery Tishkov (Director of the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology) said: “The rights of minorities and the rights of the majority can only be effective in a common space and not in isolated communities. The isolation of nationalities, both within a certain territory and in the cultural sense, may have destructive consequences for the state.”

Thus, the only way to combat xenophobia (on the part of the majority and ethnic minorities), terrorism, ethnic crime, persecutions and the reclusive nature of some regions is to form a single Russian political and civil nation. The sooner Russia works out a new modernized nationalities policy, based on civil and political community and loyalty, rather than ethnicity, the sooner the country will approach genuine unity.

Sergei Markedonov is Visiting Fellow with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Washington, USA.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox