Putin brings a trophy home from the Pamirs

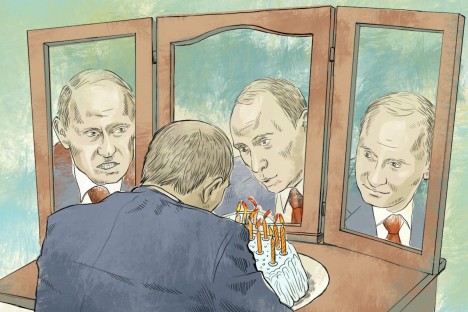

Drawing by Nstalya Mikhaylenko

The Hindus regard it as a sacred occasion when someone touches sixty years of age, which according to their ancient scriptures is the midpoint in life. It becomes an extraordinary occasion to celebrate life. Russian President Vladimir Putin couldn’t have celebrated his Shashtiabdapoorthi on Sunday with happier tidings than this.

Seventy two percent rating by the Russian people for his presidency is a fabulous tribute to any leader. Those are the figures the pollsters have just come up with. Putin’s detractors in the West who predicted a tsunami of popular opposition to the Kremlin by this autumn and winter have fallen silent.

In the culture of surfing, one would say Putin is “Hanging Ten” – an iconic manoeuvre with the back of his surfboard covered by the wave and all ten toes hanging over its nose.

But what would matter no less for him would be the trophy from the adventure sports of military diplomacy in the Pamirs, which he brought home in the weekend just in time. The trophy is all his, although he won it for Russia, since it was all personal diplomacy at one-on-one level with his counterpart in Dushanbe Emomali Rakhmon (whose Shashtiabdapoorthi, by the way, fell on Friday) that finally wrapped up the difficult negotiations over a 30-year extension of the lease for the Russian military base in Tajikistan up to the year 2042 with an option to further extend the agreement.

The prognosis until the weekend was that it could take further tortuous negotiations lasting several months before a Russian-Tajik deal could be stuck. From the details available, clearly, Tajiks do not expect a lease fee as such, which they had been demanding variously to the tune of $250 million annually. The agreement forms part of a comprehensive expansion of Russian-Tajik cooperation under a separate memorandum of understanding signed between the two defence ministries.

It stands to reason that Putin travelled to Dushanbe with a “big picture” in mind, namely, the advancement of his Eurasian Union project. Derided and dreaded by the West as a pipedream, the idea of the Eurasian Union rising out of the debris of the former Soviet Union, which Putin first espoused in the heat of the election battle as he sought a mandate for another term in the Kremlin, was supposed to languish as one of those election promises that clever politicians usually make without serious intent to fulfil. But, increasingly, it becomes apparent that Putin himself was never in two minds about the imperative of Russia becoming part of a Eurasian Union.

“Return” to Kabul

Related:

Russia’s mission in Afghanistan

Putin’s postponement of Pak visit, a great setback to Zardari government

His mission to Bishkek last month (during which Russia signed an agreement with Krygyzstan on the extension of the lease of its military bases) and the latest initiative in Dushanbe would ensure that the Russian role as the principal provider of security for the Central Asian region has been consolidated to a great extent and is being put on a long-term footing. The Russian military bases in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan become the anchor sheets of Moscow’s security strategy in the region. In turn, they become the underpinnings of the integration processes that Putin hopes to advance within the framework of the proposed Eurasian Union.

Russia’s Tajik bases are highly strategic assets, which hold profound significance for its regional strategy as a whole. Without an effective presence on the Tajik-Afghan border, Moscow’s capacity to influence the shape of things to come in Afghanistan and Central Asia would have been severely restrained. Similarly, from a logistical point of view, Kyrgyzstan is a unique hub for the communication links crisscrossing the Central Asian region.

In actuality, Russia’s “return” to Afghanistan is now on a firm footing no matter the sustained attempts by the United States to keep it at arm’s length from the Hindu Kush and to engage it only selectively as a partner in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s war efforts despite the dismal outcome of stalemate staring the western alliance on the face.

From the Indian viewpoint, a strong Russian role in Afghanistan is to be unreservedly welcomed. Russia’s commitment to forestalling the march of the forces of terrorism and religious extremism in Afghanistan and Central Asia has been unwavering like India’s and in the emergent post-2014 situation following the withdrawal of the NATO troops, this shared concern becomes extremely important for the policymaker in New Delhi.

Second, Moscow has been assiduously working for a strong partnership with the government of Hamid Karzai and has scrupulously kept away from sponsoring any particular Afghan groups. In short, the Russian policy is quintessentially the same as India’s, namely, dealing with the established government in Kabul and doing all it can to strengthen its capacity to give effective governance, and to contribute to the Afghan reconstruction.

Thirdly, neither Russia nor India is convinced about the fine distinctions that the western countries have been making from time to time between the “moderate” and “irreconcilable” extremists. Nor are they confident about the wisdom of the NATO’s “transition” plan when the security situation is patently acute. Finally, fundamental premise of the Russian and Indian policies has been that an Afghanistan that is truly independent and strong will be a factor of stability for the entire South and Central Asian region.

The fact that Karzai in a mood of growing disenchantment with the US policies last week threatened Washington that he would turn to countries like Russia and India as partners in the defence field, speaks of the close similarity in the approaches of Moscow and New Delhi on the one hand and the vast reservoir of goodwill they have succeeded in creating in the Afghan mind.

Perhaps, the time has come for Russia, India and Afghanistan to create a trilateral forum to coordinate their approaches toward the post-2014 situation. The raison d’etre of such a forum is that there are no two countries in the region that would so unreservedly contribute to the stabilization of Afghanistan as Russia and India would, for whom it is indeed a matter of their own national security.

No space for “lily pads”

On a broader geopolitical plane, though, the message cannot be lost on Washington that Moscow has firmly shut the door against the establishment of American military bases in Central Asia. The deal with Tajikistan has been struck even as Washington announced the commencement of negotiations leading to the conclusion of a US-Afghan security pact that provides for long-term American military presence in Afghanistan.

What Putin has achieved in Dushanbe is to make sure that the Americans are left with no real choice but to stick to the political parameters that they profess, namely, that it is their commitment to fight the residual terrorist forces in the Afghan-Pakistan border areas that prompts them to negotiate a US-Afghan security pact in the coming months rather than using that professed commitment as a pretext to establish their military presence in Central Asia with other geopolitical objectives in view.

The focus now turns to Uzbekistan. As a Russian expert put it, two pawns cannot be a substitute for the queen on the chessboard. Uzbekistan is a key country in Central Asia and for Moscow to have an effective regional policy, a steady partnership with Tashkent becomes the prerequisite of the situation.

The “challenge” that Uzbekistan poses to Russian diplomacy is formidable. The curious paradox is that Moscow and Tashkent are like-minded poles, which makes partnership very difficult except in a framework of genuine give-and-take, live-and-let-live. The point is, their national aspirations have much in common. It was no coincidence that even as Putin travelled to Dushanbe, a 16-member delegation from the Pentagon was touring Uzbekistan searching for suitable “lily pads”.

Besides, there is a third player that Russia increasingly has to reckon with in Tashkent – China. The Chinese-Uzbek defence cooperation is gaining traction. This process can be expected to accelerate following the upgrade of the Chinese-Uzbek relationship to a full-fledged strategic partnership, which was decided in June 2012. Significantly, during his meeting with Chinese vice-president Xi Jinping in Beijing in June, Uzbek president Islam Karimov stressed, “It is a priority to develop relations with China under new circumstances. Uzbekistan is willing to further strengthen comprehensive cooperation with China and boost the development of relations.” The “new circumstances” that Karimov had in mind could only mean the emergent post-2014 regional security scenario following the NATO’s withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Perhaps, it is only Putin who can overcome the Uzbek “challenge”, given his immense personal charisma among all Central Asian peoples and his reputation for being decisive. Putin enjoys excellent personal chemistry with the Central Asian leaderships and his fame as an “Orientalist” is unmatched among Russia’s political elites, who are largely considered to be “westernists” with no passion for the steppes.

Thus, the compromise that Putin reached in Dushanbe on Friday envisages further relaxation of Russian regulations guiding the Tajik migrant workers numbering close to a million (in a total population of 6 million). The repatriation of savings by the Tajik workers in Russia currently amounts to something like 45 percent of Tajikistan’s GDP. According to reports, Putin also kept open the possibility of Russian assistance in the construction of hydroelectric projects in Tajikistan, which could be the mainstay of its economy. Without doubt, the prospects of Tajikistan joining the Customs Union (comprising Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan) have brightened. Dushanbe largely depends on Russia for fuel imports (78.6 percent in 2011) and a waiver of customs duties alone means a saving of $350 million by Tajikistan annually.

All the same, it needs high sensitivity and far-sightedness for a powerful statesman leading a great power to bend low without vanity to accommodate the desperate needs of a tiny neighbour who may be weak but not lacking in national pride or history and culture. Even more difficult is to make timely concessions gracefully, which dovetail with self-interests as well. The fine balance that Putin struck in Dushanbe was near optimal.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox