1924: Glimpses of British India through Nicholas Roerich’s eyes

|

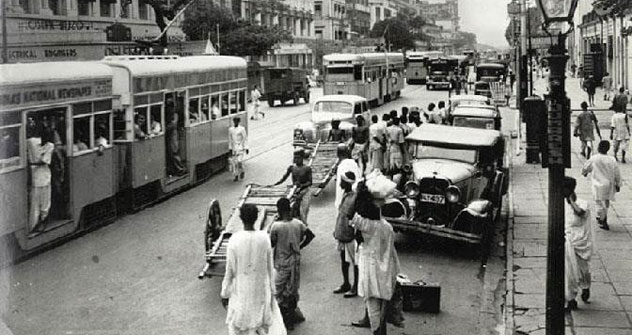

| While Roerich’s sights and thoughts were set on the Himalayas, his memoirs revealed a special liking for the Indian plains. Source: Press Photo |

“Is it really India,” Nicholas Roerich wrote as his ship from Sri Lanka approached Tamil Nadu. “A thin shore line. Meagre little trees. Crevices of desiccated soil. So does India hide its face from the South. And the black Dravidians as yet do not remind us of the Vedas and Mahabharata.” Already well-versed in Hindu and Buddhist texts, Roerich along with his family and expedition arrived in British India in 1924, a time when the struggle of independence was gathering momentum.

Roerich moved on to Madura (now Madurai) and then travelled to India’s east coast and several other parts of the country including Bombay and Jaipur. His accounts of many parts of the country 88 years ago seem all too familiar for Indians living in present-day India.

The Russian artist and philosopher went to the areas east of Grant Road station; a part of the country’s financial capital that still maintains notoriety. “In the special streets of Bombay, behind bars, sit the women prostitutes. In this living merchandise which clings close to the bars, in these outstretched hands, in their calls, is contained the whole terror of bodily desecration.” A walk to Kamathipura, the area where Roerich saw these scenes, would reveal that almost nine decades later, little has changed. India’s independence has hardly made a difference for young girls kidnapped and forced into a life of prostitution.

Not all of Roerich’s impressions of Bombay were as disturbing. He found good humour in seeing cow waiting outside the door when he left the office of the Chartered Bank of India. No one would be really surprised to see a cow walk in front of the Standard Chartered’s office near the city’s Flora Fountain.

Like many contemporary travellers to India, Roerich was enamoured by the royal city of Jaipur, where he admired the Jantar Mantar astrological observatory and the sight of Rajput princesses. “And along with this is a fantastic and romantic fragment of old Rajputana- Amber where the princesses looked down from their balconies upon the tournaments of their suitors; where every gate, every little door, astonishes one by the correlations of its beauty.”

Roerich visited Fatehpur-Sikri, the capital built by India’s great emperor Akbar, who the Russian philosopher greatly admired and called the “great Unifier of his country.” Roerich seemed genuinely sad after visiting the emperor’s capital that was abandoned in less than 15 years after its completion. “Akbar knew how the well-being which he bestowed on his people would be pillaged. Perhaps he already knew how the last Emperor of India would live to the middle of the 19th century, peddling the furniture of his palace and chipping from the walls of his palace in Delhi the fragments of mosaics.”

The Russian philosopher was also fascinated by the traditions in Benares (Varanasi). Rituals that date back to thousands of years are still performed in India’s ancient city by the Ganges. Roerich observed the sadhus, yogis and religious pilgrims by the river. “A woman quickly telling her rhythms performs her morning Pranayama on the shore. In the evening, she may again be there, sending upon the stream of the sacred river a garland of lights as prayers for the welfare of her children.” He called the garlands “prayer-inspired fireflies of the woman’s soul.”

It would take years before Roerich wrote the book Agni Yoga, but his impressions on the tour of the Indian plains helped mould his views on yoga. “We recall these Yogis who send into space their thoughts, thus constructing the coming evolution...they are bringing our thought near to the energy which will be revealed by scientists in the very near future.”

While Roerich’s sights and thoughts were set on the Himalayas, his memoirs of his time in the rest of India reveal a great degree of empathy and almost a sense of belonging to the vast plains that were protected by the great mountains. The Russian artist and philosopher fretted that the basis of worship was forgotten in Hindu temples and degraded into superstition. He aspired for an India that would preserve its ancient knowledge yet shun superstition and move towards modernity, on the lines of Swami Vivekananda’s teachings. “Vivekananda was not merely an industrious ‘Swami’- something lion-like rings in his letters. How he is needed now!”

Related:

Nicholas Roerich’s birth anniversary celebrated in Himachal

Roerich museum: an insight into the artist’s remarkable life

Roerich was an admirer of Rabindranath Tagore and Jagdish Bose, calling them the “noble images of India.” Speaking of Bose, Roerich said “the scientist approaches wholesomely all the manifestations of life. He values highly (Russian botanist Kliment) Timiryaseff’s review of his works.”

Critical of dogmatic customs and superstitions and practices that he found unacceptable like animal sacrifice and caste-based discrimination, a love of India and its people was very visible in Roerich’s writings. “The frescoes of Ajanta, the powerful Trimurthi of Elephanta, and the gigantic stupa in Sarnath, all speak of ancient times. And this former beauty also glimmers in the fine and slender silhouette of a woman who carries her eternal water; water which feeds the hearth.”

Despite the many visible changes in the last two decades, the best and worst of Roerich’s India still live on in the country’s cities and countryside.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox