Lavrov: Syria’s Assad under siege

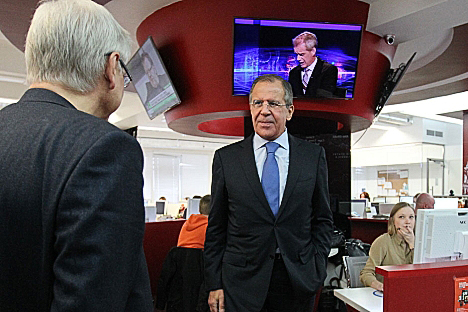

Russia's Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov visiting the RBTH editorial office. Source: Sergey Kuksin / Rossiyskaya Gazeta

The conflict in Syria has turned out to be the most drawn-out clash of the Arab Spring. Power in the country is still divided between the opposition and the incumbent head of state, Bashar Assad. Meanwhile, the rest of the world is struggling to come to an agreement on events occurring within the country. The United States and the European Union think that Assad is the main source of instability in Syria and, therefore, he must go. Russia and China, on the other hand, are not pressing for the overthrow of the Syrian leader.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov talks about why the Syrian conflict is still raging, and why the international community cannot come to an agreement.

Sergey Lavrov: Syria is indeed one of the biggest talking points at this moment in time. Something has to be done in the information space and in practical affairs to stop the bloodshed there. Sadly, the simplistic idea that, if it were not for Russia and China, everything there would have long ago simmered down is being drummed into people’s heads and is having some traction with the masses. The situation really is very serious. The whole region is on edge.

The Arab Spring is the result of George W. Bush’s foreign policy. It was he who put forward the concept of the Greater Middle East and the democratisation of the entire region. We are now reaping its fruits, because the obsession with change imposed from outside and according to external recipes was not backed up by long-term plans or, at least, medium-term forecasts and assessments. Most importantly, the slogans of change and democratisation had not been decided on with the countries in the region.

We said this much when the events of the Arab Spring began. By the same token, we were urging the external players to follow the “do no harm” principle and to do everything to create favourable external conditions that would enable all the political forces in every Arab country (or any other country, for that matter) to agree on how they would like to go about implementing reform. The same holds for Syria.

Assad has been turned into a bogeyman. But, in reality, all of these sweeping accusations that he is to blame for the whole mess are covering up a big geopolitical game. We are witnessing yet another reformatting of the geopolitical map of the Middle East, with various players trying to secure their geopolitical positions. Many are thinking not so much about Syria as they are about Iran. They openly state that Iran should be deprived of its closest ally, whom they consider to be Assad.

If one takes a broader view of what is happening, then those who are genuinely interested in stability in the region and in creating conditions for its prosperity (the resources are there) should follow not the logic of isolation – which is being used with regard to Iran and was, still earlier, used with regard to Syria – but the logic of engagement. To our great regret, our Western partners all too often opt for the logic of isolation, resort to coercive measures and seek to introduce unilateral sanctions without the approval of the U.N. Security Council in order to bring about regime change.

We believe that this approach is counterproductive. Recipes imposed from outside will never yield a sustainable result. Such a result can only be achieved through dialogue. These principles fully apply to the situation in Syria.

Following the principle of engagement, we have, from the very beginning of the crisis, worked tirelessly to see an end to all kinds of violence in the country and to ensure that the channels for an inclusive dialogue between the government and all of the opposition groups are opened. That is why, one year ago, we backed the Arab League initiative, which involved the deployment of Arab observers. They started work in the country with the consent of the Syrian leadership, and we did a great deal to secure this consent. However, as soon as the observers produced their first report – which did not put all the blame for the continued violence solely on the government forces, but gave an objective, albeit incomplete, picture of what the armed opposition was doing – the Arab League, unfortunately, curtailed its mission.

Kofi Annan’s plan soon followed. It also implied the start of a dialogue. To this end, a U.N. observer mission to Syria was proposed. Potential observers were agreed upon with Damascus, also with our assistance. But as soon as early results came through and violence began to subside a little, the observers became targets of ever more frequent armed provocations. They found themselves working under impossible conditions and were recalled as well.

It seems that, as soon as there is some light at the end of the tunnel, some quarters seek to prevent the situation from following a calmer course; it is in someone’s interests for the bloodshed – the civil war – in Syria to continue.

I repeat: Russia is honestly seeking to bring home to the Syrian Government and the opposition that there is no alternative to ceasefire and negotiations. At our proposal, which coincided with Kofi Annan’s initiative, a meeting of the Action Group for Syria was held in Geneva on June 30, 2012, and a consensus document that came to be known as the Geneva Communique was drawn. It urges all those who are fighting to put down their arms. It also compels external players in the conflict to use their influence with the various parties to make them simultaneously declare a ceasefire and start negotiations by way of delegating representatives.

The communique was adopted by consensus; this reflects the collectively agreed upon, joint position of the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council, the Arab League, Turkey, the European Union and the United Nations. Bashar Assad supported the document and appointed his negotiator. The opposition ignored it; not only did they fail to appoint a negotiating team, but they also flat out rejected the Geneva Communique.

What is particularly distressing is that the opposition increasingly resorts to the tactics of terrorist attacks. Our Western partners, contrary to the long-established and immutable practice, stopped condemning such terrorist attacks at the U.N. Security Council. The Americans, through the mouth of a State Department spokesman, even said that Assad’s continued stay in power was fuelling extremist sentiments. This is nothing if not an indirect justification of terrorist attacks. I think this is a very dangerous position that may boomerang against those who adopt it.

The article is abridged and first published in Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox