Separatism: The idea that won’t die

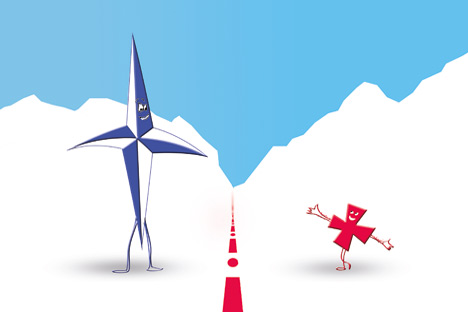

Drawing by Niyaz Karim

Separatism rears its head again. Secession petitions began circulating in many US states after President Barack Obama won re-election. Secession supporters believe they would be better off on their own than as part of a country led by Obama, especially in Texas, a prosperous and conservative state that rejects Obama’s creeping “socialism.” Obviously, no US states will actually secede, but it is telling that this issue has again come to the fore.

Pro-secession sentiment is running high in Spain’s Catalonia region, which just held parliamentary elections. Although the centre-right Convergence and Union (CiU) movement failed to win an absolute majority, raising doubts about the planned independence referendum, it can make common cause with smaller pro-independence parties to form a government that will work toward Catalan self-determination. The Spanish Constitution may not provide for independence referendums or the right to secede, but Madrid cannot completely ignore the mood in Catalonia, which represents one-fifth of the national economy.

The global economic crisis has sapped feelings of national unity among richer regions, which spend more time thinking about how much they transfer to their poorer neighbours and how well they could live without these dependents. This sentiment is very strong in Belgium’s Flanders and in northern Italy, as well as in Scotland, which, though not the most prosperous part of the UK, lays claim to North Sea hydrocarbon resources.

Russians and the peoples of other former Soviet republics once had dreams of sovereignty – dreams that ended in the nightmare of the Soviet Union’s collapse. The main catalyst was the Russian Federation itself, where a growing number of independence backers, including those who claimed to be economists, painted pictures of post-secession economic prosperity in the late 1980s. Several Soviet republics complained about their “parasitic neighbours.” But none of them benefitted from the collapse of the Soviet Union, and it took 20 years to adjust to independence. They are now trying to restore severed production chains, but some of the losses are irreversible.

Of course, economic benefits are not the only – and possibly not even the main – reason behind the rise of separatist sentiment. It is natural to want national independence. The age of empires ended in the 20th century, and even attempts to create a new type of empire based on the voluntary delegation of powers, such as the European Union, have faced daunting obstacles. The events of the late-20th century show that the undeniable right to independence does not guarantee the formation of a competent and successful state. But this is only clear later, when secession is irreversible.

It is individual politicians pursuing their own interests who are often the most ardent secessionists. The new issue of the US magazine Foreign Affairs contains an article by Charles King, an expert on separatism, about Scotland’s “quest for independence and the future of separatism.” Although Scots have always had a distinct national identity, First Minister of Scotland Alex Salmond is fuelling independence sentiment for political gain. His Scottish National Party (SNP), the majority faction in Scotland's parliament, is fighting to secure a monopoly on power: in an independent Scotland if the referendum succeeds or, if it fails, in a Scotland with “increased policymaking power short of full sovereignty.” The same logic applies to Catalan separatists, because politicians in a democratic country where elections are held regularly need a failsafe bargaining chip.

Charles King makes another vital point: independence movements are catalysed by the existence of such political institutions as a local parliament, a local government and clear borders between autonomies. These elements allow nationalists to transform the dreams of ordinary people into political action. This explains the enduring stability of Ukraine, despite the fact that it is being virtually torn apart and has been discussing dissolution for nearly 20 years. The simple, inescapable problem is that no one knows where to draw the borders of potential new states.

The most prominent cases of dissolution involve federations, which break up along their administrative borders. But these borders rarely reflect the true boundaries between ethnic groups, as the empires that drew them did so arbitrarily, without the expectation that they would one day become national borders. This is why unitary states, even those that are not ethnically homogenous, are more stable: any attempt by a federative state to appease a region by delegating more powers to it often just stokes independence sentiment.

This does not mean that Russia should renounce federalism, contrary to the views of some Russian politicians who propose recreating the provinces of the Russian empire. Any attempt to strip a region of its autonomy can have disastrous consequences: the dissolution of Yugoslavia began in 1989, when the central authorities hemmed in Kosovo’s autonomy.

The rise of separatist sentiment in Europe will not necessarily lead to the emergence of new states. Europeans, especially Western Europeans, have a rational attitude to history-making referendums. The United States will not break up either. And Russia seems to have defeated the virus of separatism, which killed the Soviet Union and almost destroyed the Russian Federation in the 1990s.

On the other hand, the hope that globalisation will resolve the issue of nationalism once and for all has not materialised. Given the growing unification of the world – contrary to the will of nations and governments – some nations logically cling to what is familiar. And so secessionism will go hand in hand with the desire to be part of something bigger.

Fyodor Lukyanov is editor-in-chief of the journal Russia in Global Affairs.

First published in RIA Novosti.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox