|

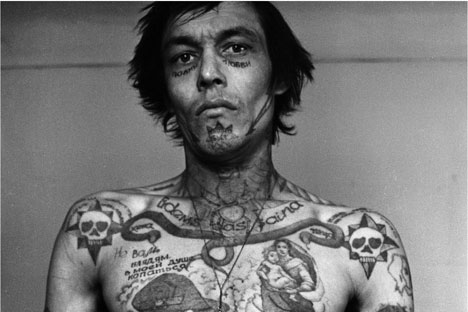

| Tattoo print by Sergei Vasiliev, Source: Courtesy of Saatchi Gallery. |

The Saatchi Gallery’s first exhibition of contemporary Russian art opened late November in London. Charles Saatchi’s tastes as a collector tend towards hard-hitting works that shock the viewer and the current show is no exception.

It intersperses photography and installations with paintings, like Valery Koshlyakov’s monumental buildings, daubed on disintegrating cardboard, or Dasha Shishkin’s detailed multi-colored satires with their mutant, long-nosed socialites in designer dresses.

The works are interesting enough, but the timing is unfortunate. The fact that this huge, sometimes overbearing show coincides with a display of really remarkable Moscow art from the 1960s to 1980s (on the top floor) means the historic exhibition has so far gotten less attention than it should.

There are things worth seeing in “Gaiety is the Most Outstanding Feature of the Soviet Union,” but it is erratic.

The ironic and cumbersome title is a quote from a 1935 speech by Stalin. It does little to illuminate the works on show, all of which were made since the break-up of the Soviet Union, except in its heavy-handed highlighting of the continuing bleakness of some aspects of Russian life and exploration of Soviet legacy. Physical deterioration and mutilation are recurrent themes.

The show opens with an arresting room full of larger-than-life-sized criminal tattoos, photographed in black and white by Sergei Vasiliev. There is a powerful contrast between the writhing pictures on their bodies and the calm resignation of the prisoners’ faces. Vikenti Nilin’s photographs are equally compelling. His series “Neighbours” shows people sitting peacefully on the window ledges of Soviet tower blocks. In some shots, we look over the shoulder of a man in a suit to see the five-floor drop beneath his dangling feet.

The exhibition guide suggests the passivity of Nilin’s suspended Muscovites could allude “to the state of politics in his home country.”

At the other end of the subtlety spectrum, the un-ignorable work of Gosha Ostretsov spells out its political statements in neon-splattered, cartoonish installations.

“Criminal Government” shows a row of cells (whose numbers are variations on 666) in which individuals in suits and masks are mutilated, dead or dying. Painted, latex masks have featured in several of Ostretsov’s exhibitions and performances exploring power. Although his work looks like a teenager’s bedroom, he is not particularly young. Born in Moscow in 1967, he is now working there again, after a decade in Paris.

Among other engaging works on show are Daniel Bragin’s “Bedtime Story,” a kid’s blanket made of smashed windscreens, and Dasha Fursey’s “Boundary Post of a Cat Bajun,” a glass-jar-tower containing pickled cucumbers, berries and mushrooms.

There are jars like these in numerous Russian kitchens, but out of context they become reminiscent of Peter the Great’s “Kunstkamera” with its bottled babies; the title’s mythological storytelling cat suggests the nostalgic and territorial significance of what Fursey has called “the Soviet cult.”

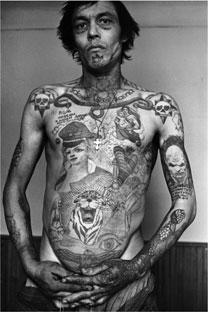

|

| Homeless people by Boris Mikhailov. Source: Courtesy of Saatchi Gallery. |

On the next floor up, Boris Mikhailov’s intimate and moving photographs show homeless people, their bodies often naked, scarred or suppurating, their faces prematurely aged. The smaller prints draw the viewer in, while the wall-sized ones repel.

From the emaciated, but cheerful children to an old man in a snow-covered coat, with a church in the background, who seems to be asking an unanswerable question, these are memorable images. The photographer’s aim was to catalogue the lives of “people who got into trouble but didn’t manage to harden so far.”

Mikhailov’s pictures are a record of communism’s aftermath, producing “creatures that were once humans,” but are now “degraded, ghastly, appalling.”

Mikhailov, born in what is now Ukraine in 1938, is the only really well-known figure in the exhibition.

Like Vasiliev, he is an exception to the theme of young and emerging artists. His epic series of 413 photographs, “Case History”, documents the post-Soviet disintegration of life in his native Kharkov. The title suggests the progress of a disease, one that Mikhailov insists (in quotations reproduced on the gallery’s website) is specific in time and place: “What happened on the ruins of the ex-Soviet Empire is still unique.”

“Gaiety is the Most Outstanding Feature of the Soviet Union” runs at the Saatchi Gallery until 5 May 2013

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox