Demystifying the life of Grigory Rasputin

The most amusing aspect of this work for these Rasputin scholars has been the number of false Rasputin descendants who have presented themselves. Source: Andrei Shapran

The Tobolsk tract, along which convicts were once herded to Siberia, used to run through the village of Pokrovskoe in the Tyumen region, and the windows of Grigory Rasputin’s house used to look out on this road. Today, the road skirts the village and Rasputin’s house has been pulled down; but opposite the place where it stood, with a brightly painted wooden fence and carved lintels, is a museum devoted to “the most famous Russian” – the man who gave his name to thousands of restaurants and some bad German vodka.

By the gates stands a stone engraved with a brief excerpt from the diary of Czar Nicholas II: “We changed horses in the village of Pokrovskoe. We waited for a long time just opposite Grigory’s (Rasputin’s) house.”

Two months later, Nicholas II, his beloved wife Alexandra, the four princesses, the 13-year-old czarevich Aleksei and three servants were murdered in the cellar of the Ipatiev House in Yekaterinburg.

Since the 1970s, Vladimir and Marina Smirnov have been collecting Rasputin’s documents, letters, photographs and belongings. In 1991, they created Russia’s first private museum and dedicated it to Rasputin, who, in the Smirnovs’ opinion, is “the world’s most famous Russian.” To this end, they bought the old two-story house in Pokrovskoe (in the Yarkovsky district of the Tyumen region) where Rasputin’s parents had once lived. The museum consists of two small rooms, but they contain a number of belongings from Rasputin’s house: unique photographs and documents, which the Smirnovs found in archives, bought at auction (Sotheby’s), and obtained from people whose ancestors had known the “great Russian mystic.”

After Rasputin was murdered and his family had been deported to Salekhard, the Peasant Poverty Committee divided up his property amongst “their own.” The Smirnovs dug up the lists of the relevant parties and made rounds to the houses of their descendants in Pokrovskoe. This is how they came by the bentwood chair, the broken mirror, the dish with the monogram of the Czarina Alexandra Fyodorovna, the doorbell and other things belonging to the imperial spiritual advisor.

The museum’s collection also includes some bottles of Rasputin vodka and various books about him – from serious scholarly investigations, to recipes for various poultices and decoctions attributed to Rasputin.

The Smirnovs managed to establish Rasputin’s exact date of birth, discover the history of his family’s origin, and even find a genuine great-granddaughter of the great mystic – her name is Laurance Io-Solovieff, and she now lives in Paris. Like almost everything connected with Rasputin, the year of his birth, his family origins and the fate of his descendants remained the stuff of historical novels for decades.

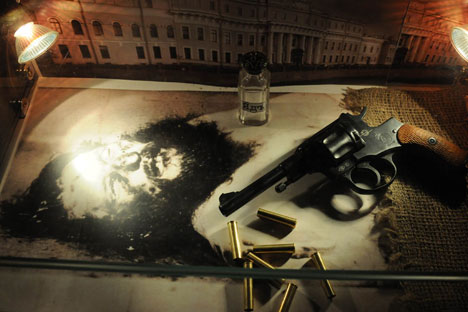

Like Rasputin’s life, his death too remains shrouded in falsifications and mysteries. Source: Andrei Shapran

After making an inquiry at the Yarkovsky Registry Office in the Tyumen region, Vladimir Smirnov found the parish register that contains the following entry for January 9, 1869: “In the village of Pokrovskoe, in the family of the peasant Yefim Yakovlevich Rasputin and his wife, both Orthodox, was born a son, Grigory.”

“The Encyclopedia Britannica sent us a certificate saying they had corrected Rasputin’s year of birth,” said Smirnov with evident pride.

The most amusing aspect of this work for these Rasputin scholars has been the number of false Rasputin descendants who have presented themselves. The Smirnovs have already lost count of the direct and illegitimate “heirs” of the bearded Russian mystic.

“More than a hundred Marias, Anastasias and Alekseis survived execution in the cellar of the Ipatiev House. Now it’s the turn of Rasputin’s descendants,” said Vladimir.

Of Rasputin’s three children, only his daughter Matryona had children. His son Dmitry had no children; he died with his wife Fesha in a barrack on a special labor settlement in Salekhard. His other daughter, Varya, never married. In 1925, she died of typhoid in Moscow and was buried in Novodevichiy Cemetery.

Matryona and her husband, the White Army officer Solovyov, left Russia with a contingent of White Czechs on the last ship to depart Vladivostok. Her husband soon died; for the sake of her daughter she was obliged to work in a circus as a tamer of wild beasts. The crowds especially liked her name on the playbill: Maria Rasputina.

In 2005, Rasputin’s Parisian great-granddaughter Laurance came to Pokrovskoe and presented the museum with authentic photographs and documents. Curiously, Laurance had kept her friends in the dark about her famous ancestor for many years: it was not until she turned 60 that she told them her great-grandfather’s name.

As for the stereotype of Rasputin as a drunk and a libertine, Vladimir Smirnov takes the sort of view that befits a museum curator: he understands that the world is not perfect. “Rasputin built a church in Pokrovskoe with his own money; he founded a temperance society; he taught his children to give to the poor; he did not eat meat or milk; and he went on pilgrimages to many sacred Christian sites, including the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Although he was illiterate, he knew the Holy Scripture by heart and interpreted it so graphically that he astounded not only the church hierarchy, but the czar’s family…”

Like Rasputin’s life, his death too remains shrouded in falsifications and mysteries. He was murdered on the night of December 17, 1916, as the result of a plot against him organized by Felix Yusupov, Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, British MI6 agent Oswald Rayner, and monarchist Vladimir Purishkevich. It is thought that Rasputin was poisoned with potassium cyanide that had been sprinkled on some of the cakes that were served; but Rasputin did not eat any of the cakes, and the coroner found none of the fatal poison in his body.

Most likely, says Smirnov, Rasputin was savagely beaten and then shot several times – in the head, stomach and back. Then, his assailants bound his arms to his body, wrapped him in a drape, and threw him into the Malaya Nevka.

“When Rasputin’s body was pulled from the water on the czar’s orders, it turned out that his arms were free and that his right was raised and the first three fingers were pressed together as if, realizing that he would not make it to the surface of the water, he meant to cross himself,” said Vladimir.

Other sources claim that Rasputin was already dead when his murderers threw him into the water. When Rasputin made the acquaintance of John of Kronstadt, the future saint, the father asked him his name. “Rasputin,” the mystic replied. Then Father John said: “Mark my words: you will be as your name.” And so Rasputin was. In Russian, “rasputnik” means “libertine.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox