The women behind Russia’s most famous writers

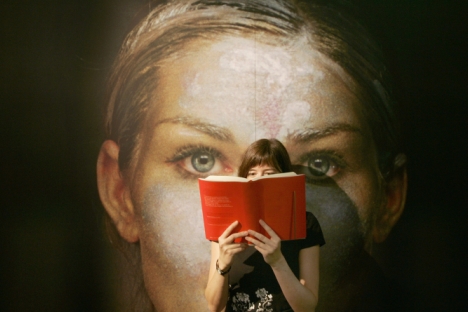

Some women even risked their lives for the sake of their husbands' work. Source: ITAR-TASS

Nadezhda Mandelstam's brother once commented that she and her husband - the brilliant, doomed poet Osip Mandelstam - were becoming so close that "Nadezhda" seemed no longer to exist.

"That's how we like it," she replied.

Russia's most celebrated writers - including Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Nabokov, Bulgakov, Solzhenitsyn and Mandelstam - are often depicted as solitary geniuses. But many of their works were the fruits of creative partnerships with their wives. Far from being passive typists, they served as editors, researchers, translators, publishers and more.

"What people know about is that Sophia copied out Tolstoy's great novels, but it was much more than that," said Alexandra Popoff, author of the 2012 book "The Wives: The Women behind Russia's Literary Giants." "They discussed things together - there was a spark. And without it, the ‘War and Peace' that the world admires wouldn't have been written."

Popoff was born in Moscow and now lives in Canada. Her inspiration for the book was her mother's own collaboration with her father, novelist Grigory Bakhlanov. "He read what he wrote during the day to her," Popoff said during an interview in Moscow. "She would simply say, ‘you could do better,' or ‘I don't feel it.' She was his best editor."

Popoff considers her parents' relationship part of a uniquely Russian tradition. English literature could claim prominent female writers going back to Aphra Behn, the 17th century dramatist. Western literary wives such as Zelda Fitzgerald and Martha Gellhorn (Ernest Hemingway's wife), she writes, had little interest in, as Gellhorn put it, "being a footnote in someone else's life."

But until the mid-20th century, Russian prose was dominated almost entirely by men, who were lionized as national heroes. Their wives were expected to dedicate themselves to cultivating their husbands' genius - a role many played to the hilt.

The model was established by the Dostoevskys and the Tolstoys. Sophia Tolstoy copied her husband's works, diaries and letters, working through the night after tending to their estate and 12 children during the day. She also served as muse, inspiring Kitty and Levin's love affair in "Anna Karenina."

Dostoevsky dictated both "Crime and Punishment" and "The Brothers Karamazov" to his wife Anna, and infused many of his characters with her traits. "Fyodor Mikhailovich was my idol, my god," Anna wrote, eternally faithful even after nursing him through a gambling addiction that reduced her to rags.

These archetypes were mimicked, sometimes consciously, by later couples. Before their marriage, Tolstoy gave Sophia a written account of his previous sexual exploits (including contracting gonorrhea from a prostitute), an episode he recreated in "Anna Karenina." Nabokov, who idolized Tolstoy, did the same with his wife Vera.

Some women even risked their lives for the sake of their husbands' work. Natalia Solzhenitsyn met her future husband, already famous for "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich," when she was a 28-year-old doctoral candidate. Beyond performing extensive research for his historical novels, as well as editing and typesetting his collected works, she engineered the smuggling of his works to the West - preserving "The Gulag Archipelago" and other crucial texts.

Mikhail Bulgakov based the character of Margarita on his wife Yelena Many continued to work for their husbands in their widowhood. Yelena Bulgakova fought tirelessly to ensure the publication of "The Master and Margarita" after her husband's death (in keeping with her portrayal in the novel as Margarita, the ultimate writer's wife). After Osip Mandelstam perished in a camp, Nadezhda lugged his secret archive across the Soviet Union. (Nadezhda went on to write two fine memoirs of her own, "Hope against Hope" and "Hope Abandoned").

Such relationships tended to be all-consuming. As Nabokov would put it, he and Vera were "a single shadow." Dostoevsky, Mandelstam and Nabokov all said they couldn't write without their wives nearby. Anna Akhmatova, for one, was astounded.

"He wouldn't let her out of his sight, didn't let her work, was insanely jealous, and asked her advice on every word in his poems," she said after seeing Mandelstam with Nadezhda. "In general, I have never seen anything like it."

Sometimes this dependence was even physical. Both Nadezhda Mandelstam and Vera Nabokov could be seen lugging heavy cases, while their husbands strolled around unencumbered.

But some women found this self-immolation too much to bear. Sophia Tolstoy was a spirited painter and writer; her husband took the name of his heroine in "War and Peace" from a youthful novella of hers, "Natasha." But in the midst of her husband's religious conversion, she began to regret her devotion.

"Everyone asks: ‘But why should a worthless woman like you need an intellectual life or artistic life?'" she wrote in her memoir "My Life," which was only published in 2010. "To this question I can only reply: ‘I don't know, but eternally suppressing it to serve a genius is a great misfortune.'"

After Sophia ceded her role as confidant to Tolstoy's disciple Vladimir Chertkov, she found herself excluded from his circle entirely. His acolytes even refused to allow her near his deathbed. Thanks largely to Chertkov's influence, Sophia was long portrayed as "a henpecking wife who couldn't appreciate [Tolstoy's] moral genius," said Tolstoy scholar Andrew Kaufman, author of "Understanding Tolstoy."

But according to Kaufman, modern attitudes are shifting. "With glasnost and perestroika and their long aftermath, Russians have become more ready to humanize and even criticize their greats, and find fault with their moral hypocrisies," he said. "The general antipathy towards Tolstoy's moral extremism, and how he treated his wife and kids, has been part of this trend."

Today, with Russian writers such as Lyudmila Petrushevskaya and Tatyana Tolstaya winning international acclaim, the sort of relationships described in the book seem a thing of the past. "Now, women would rather establish their own careers than dedicate their lives to their husbands," Popoff said. But Popoff said there are many other couples, such as Andrei Bely and his wife Klavdia Bugaev, whose stories remain to be told. "You don't know where the collaboration begins and where it ends," she said. "These women were so much in this literature."

First published in The Moscow News.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox