Death masks: A look at the Soviet Union’s most macabre art

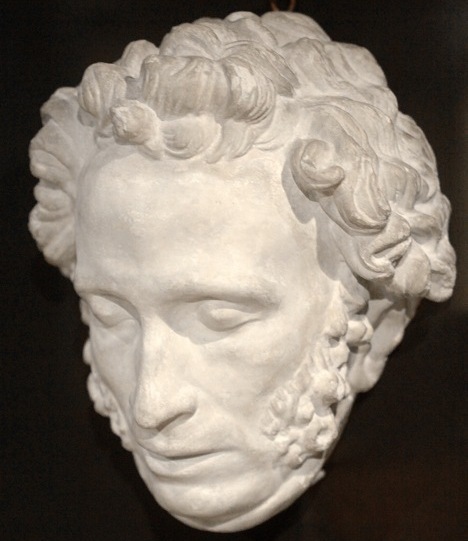

In the 19th century, masks became an after-death essential for Russian royals and cultural luminaries including Alexander Pushkin. Source: ITAR-TASS

On the night of January 21, 1924, sculptor Sergei Merkurov was packed into a horse-drawn carriage on a secret assignment. Shivering in the -30 degrees Celsius cold, he still didn't realize where he was going as the carriage pulled into Vladimir Lenin's estate outside Moscow.

It was only when he saw Lenin lying in bed, dead after his fourth stroke, that he realized the task before him.

"You were planning to sculpt a bust of Lenin," whispered Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin's widow. "Now, you must make a mask."

This plaster cast of Lenin's visage - along with his hands, one permanently clenched following the second stroke that paralyzed his right side - marks the beginning of "Masks Shock," a new exhibit at Gorki Leninskiye, Lenin's estate-turned-museum.

Trotsky’s mask is highly sought-after among collectors.

In a dark basement corridor in the mansion where Lenin died - the clocks forever stopped at 6:50 p. m., his time of death - the mask is united with those of a dozen other Soviet figures. Joseph Stalin's mask lies a few feet away from that of his nemesis Leon Trotsky, who was murdered with an ice pick on Stalin's orders.

Krupskaya, Cheka founder Felix Dzerzhinsky and poets Sergei Yesenin and Vladimir Mayakovsky are a few of the other masks on display.

"You and I, we wear masks on our faces - we smile, we control our expressions," said Natalia Mushits, the museum's head researcher. "But at the moment of death, a person's true face is revealed.

"This true face is fixed by the death mask."

The tradition stems from ancient Egypt, when an idealized sculpture of the deceased's face was laid in his or her tomb for the afterlife. The Romans made wax funerary masks, which then served as the basis for stone sculptures.

In the late 14th century, the tradition spread to the monarchies of Europe. Casts were made directly from the face using wax or plaster, then displayed during funeral rites and preserved for posterity in museums and libraries. Henry VIII, Beethoven and Napoleon were a few of the icons to have their visages immortalized.

In Russia, the first death mask belonged to Peter the Great. In the 19th century, masks became an after-death essential for Russian royals and cultural luminaries including Alexander Pushkin.

Lenin's mummified body - which recently reopened for visitation after months of repairs - is the most famous example of Soviet post-mortem culture. But the Soviets used death masks to a far greater extent, with the faces of countless Central Committee members preserved in plaster.

The circumstances of their creation varied widely. Swashbuckling revolutionary Grigory Kotovsky was murdered near Odessa in 1925 by his deputy, supposedly for having an affair with the latter's wife. His mask was created by a soldier with no artistic training.

"It didn't turn out very well," said Dmitry Shlyonsky, a death mask historian and collector.

The soldier himself was killed shortly thereafter. (Kotovsky, who had a vibrant cult of personality, was mummified and displayed in his own Ukrainian mausoleum, which was destroyed in 1941).

Mayakovsky also fell victim to poor craftsmanship. After the poet shot himself in his Moscow apartment, a sculptor was quickly summoned. But the resultant mask distorted Mayakovsky's features, giving the dashing author of "A Cloud in Trousers" an oddly misshapen look.

The master of the Soviet death mask was Sergei Merkurov, who made up to 300 masks before dying in 1952. A celebrated artist, Merkurov served as head of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts after World War II.

He was also a lifelong mystic with a fixation on death.

"My entire life, death stood before me in its terrible greatness," Merkurov wrote in his recently published memoirs.

His handiwork includes the death masks of Lenin, Dzerzhinsky, party leaders Yakov Sverdlov and Mikhail Kalinin, and Leningrad boss Sergei Kirov, whose murder provided the pretext for Stalin's Terror.

Merkurov elevated the death mask from a simple mold to an "art form," Shlyonsky said. After casting the subject's head, he often transformed the work into a full sculpture, adding hair and clothing. His best-known work is his monumental death mask-turned-statue of Leo Tolstoy, which shows the writer tucking his hands into his belt like a peasant.

His work on Lenin's mask ignited his career - but it began with a terrible scare.

Some say a dent in the forehead of Yesenin’s mask suggests foul play

Putting his hands on Lenin's head that night, Merkurov suddenly felt a pulse. Startled, he called for Krupskaya, as well as the doctor who declared Lenin dead.

Taking hold of Merkurov's wrist, the doctor kept it still until the sculptor felt his pulse. It was not Lenin's heartbeat he had sensed, but his own.

Merkurov's mask of Lenin would serve as the basis for thousands of statues, including a massive Lenin carved in red granite for the 1937 World's Fair in New York.

Many of the figures whose masks are at the exhibit died under mysterious circumstances, as pointed out by a reel of archival film footage depicting the figures in life.

A mask can provide clues as to "whether the deceased left this world willingly, or whether he was helped along the way," Mushits said.

She points to a dent in the forehead of Yesenin's mask to suggest that he may have been murdered, rather than hung by his own hand.

In the narrow corridor, the masks lie illuminated under eerie green light. Across from each is a mirror, playing on the belief that the soul is preserved in the dead man's reflection. Visitors squeeze through in single file, to the ominous intonations of a soundtrack full of haunting chords.

Museum head Igor Konyshev said the exhibit's unusual presentation was "an attempt to attract young people."

A female visitor behind a reporter cursed under her breath as she hurried out of the darkened tunnel. "Honestly, it's very strange," she said, before heading for the door.

After Stalin's death, the culture of death masks became less visible, but it remained alive and well. Brezhnev, Andropov and other late Soviet figures were all memorialized in death masks, as was bard Vladimir Vysotsky.

Shlyonsky says the last known death mask of a Russian leader is Boris Yeltsin's. The family has denied owning it, but "people I know in Moscow say it exists," he said.

Trotsky's death mask is among the most sought-after. After the exiled revolutionary was assassinated by an NKVD agent in his Mexico City home, his wife commissioned artist Ignacio Asunsolo to make his mask. Upon her death in 1962, a small number of copies were made. The original was sold in Paris to French anarchists; in 1979, it was resold for "an insane amount of money" to Britain's Workers Revolutionary Party.

One of the copies made it to Russia only in 2009. It was loaned to the museum by an anonymous collector.

The exhibit's final slot is left open, with visitors asked who else's mask they'd like to see on display. "It's for Putin," Mushits said.

"Masks Shock" is on display until Sep. 1 at the Gorki Leninskiye State Historical Museum-Estate.

First publsihed in The Moscow News.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox