Is there landscape design in Russia?

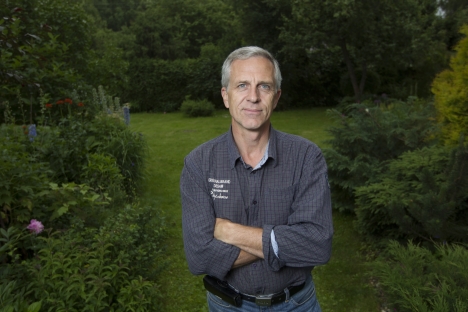

Andrei Lysikov was one of the very first in Russia to proffer his services in the area of landscape design, he started his business in 1991. Sourse: Sergey Mikheev/RG

The Russian word “dacha” has entered the English language and no longer needs any kind of translation. Russians are renowned the world over for their enthusiasm for the great outdoors. Russian summer relaxation begins with overcrowded suburban trains, mile-long traffic jams and squabbles for parking spots near city parks.

Despite this, the popular concept of landscape design, so well-known elsewhere, still doesn’t feature on Russian radar and remains the peculiar whim of the well-heeled alone.

Behind neighboring hedges we hear the authentic thrum of life at the dacha: The trimmer whirls, a hammer thumps and the radio gurgles monotonously in the background.

But at the dacha of landscape design specialist Andrei Lysikov, things are rather different. It’s the same standard Soviet-sized dacha plot of 6,458 square feet – but there are no lines of vegetables and no greenhouse.

Rossiyskaya Gazeta: Who were the first to make use of landscape design services in Russia?

Andrei Lysikov: We set up the first landscaping service in 1991. Making a place green is a pretty expensive pursuit. The people who could afford it back then were mostly from a very specific background – people with money that hadn’t necessarily been come by in entirely legal ways – the New Russians.

RG: And what kind of services did they want?

A.L.: Mostly they just asked us to “make it look nice.” The first job, of course, was to put up a dense hedge all the way around the perimeter. Sometimes they made the hedge 10-meters-high [about 33 feet], planting three rows of trees – spruce or cypress, usually. Sometimes they were blunt about it, saying it’s to be safe from sniper fire.

What landscape design actually was and what it involved were things that neither the clients nor the providers understood very clearly. There were very few books about it. Nobody had really done much private gardening – but they yearned for beauty.

RG: So how are things today? Are they still crouching for shelter behind the cypresses?

A.L.: No, not now. The clients don’t just ask to make it beautiful. Many of them are following the trends. They’ve heard of the famous designers and their work. The landscapers aren’t sitting idle either: Many real professionals have appeared; people even get hired to come from abroad.

Any self-respecting designer thinks their duty lies in defending their ideas from their clients. The clients are still full of the wildest fantasies.

For example, Japanese gardens are all the rage now, but people ask for them both where they’d be good and where they’d be really wrong – alongside birch trees and oaks.

It used to be that designers only worked for wealthy clients. But competition is on the rise, and, today, people with quite middling incomes can afford the services of a professional.

Even so, on a six-hundred-meter [6,458-foot] plot of land – the standard size we have in Russia – you won’t find too many designers rushing in. It’s too small, unprofitable, and there’s nowhere to roam.

RG: Okay! So the work week’s over, thousands of people are stuck in traffic jams heading out of town, and all dreaming of getting a spade in their hands. It seems like there’s nowhere else on Earth where people have such a yearning for the land. What can we learn from abroad?

A.L.: We’re used to thinking of land in terms of what we can get out of it.

A dacha means cucumbers, tomatoes – or else the chance to relax, or potter about. Some people like a sauna or a barbeque. But a garden – well, that’s beauty encapsulated.

The trend in people wanting to beautify the world around them is a sign of culture within ourselves. It all begins with the smallest stuff – a little bush in the courtyard, or even on the balcony of our apartment. It’s all a good sign.

{***}

At the dacha of landscape design specialist Andrei Lysiko there are no lines of vegetables and no greenhouse. Source: Sergey Mikheev/RG

RG: You travel a great deal and organize special trips for garden-lovers. Can you tell us about other countries – for example, British landscape design? Is it just a rich man’s plaything there too?

Elena Lysikova: No, not at all. People who live in quite small townhouses are keen gardeners – anyone who’s got a tiny bit of land can do something with it. There are heaps of magazines about gardening there, and garden tours are very popular.

A.L.: There was one time when we took a tour group to a garden that was looked after by a married couple. After they bought their house, they found out that, at one time, the garden was looked after by the legendary gardening artist Gertrude Jekyll.

The new owners discovered drawing and diagrams from the early 20th century in an American library – and they restored the garden. It’s about a hectare [2.5 acres] in size. There are three of them looking after it: the lady owner, her sister, and one paid gardener who comes to help.

RG: But surely this is a rare exception to the norm?

E.L.: Not really! Very often, gardens up to a hectare in size can be managed by their owners alone. Assistance from professional gardeners is used from time to time.

Related:

Farmers’ markets are in season in Russia

Design Saturday festival aims to promote eco-friendly living

For us, as Russians, it’s hard to imagine that a wealthy individual might work the soil and not be ashamed of doing so.

During one of the trips around an estate that has been in the same family for six hundred years, the owner himself came to meet us. He was dressed quite scruffily, and his hands showed that he was used to working on the land.

One of the women on the tour, who hadn’t been paying much attention during the commentary, asked the man, “do you work here as the gardener?” He smiled politely and then explained, “Actually, I’m the lord – I own the land here.”

RG: Would you say garden tourism is popular with Russians?

A.L.: Well, it’s not exactly a mass-market thing; but it’s also true that it’s not only professionals who are interested. Some gardening fans are very keen – they know all the species, the trends and what’s new.

Then there’s a second category of well-to-do ladies, who have their own country homes: They don’t just want to make their gardens pretty, but to do it with style too. They’re often to be found studying courses on landscape design, learning to tell their garden workers what to do. I’ve seen several cases where women from this background turn out to be first-class garden designers.

And, finally, the tours attract the publishers of specialist magazines, and photographers; and with a slow increase in interest, the garden tours are growing. Of course, it’s not especially cheap, as each itinerary is worked out individually to suit everyone’s tastes. The cheapest routes typically cost around 50,000 rubles [approximately $1,500] for a week’s tour.

RG: Even Moscow’s civic parks have recently taken on a new lease of life. The best example is Gorky Park – the garden layout and flowerbeds have been managed by real professionals.

E.L.:Gorky Park is a really unusual example in Russia – they gave the professionals the money and told them they had complete freedom to do whatever they wanted. And the public is enjoying the results of all that.

But, regrettably, in the rest of Moscow they can’t even do basic stuff like laying out the flowerbeds and gardens without resorting to the worst, old, Soviet clichés. The work is carried out on a perfunctory basis – but without any enthusiasm, and often without even basic ability.

First published in Russian in Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox