Musicians of an openly avant-garde genre that is “not for everyone”—musicians who lack wide recognition in Russia and could be monetized abroad—have released albums in the West and had success. Source: Press photo

This is the second installment of Leo Fest in Russia. This year, it will include musicians from Siberia and the Russian North, along with saxophonist Sergei Letov and multi-instrumentalist Sergei Starostin — both of whom are stars of the genre.

As part of the festival, Leo Feigin will personally present a film series entitled “New Music from Russia.” Some of the musicians are already well-known, while some have yet to be discovered. Feigin promises everything except the ordinary: “Expect the unexpected!”

|

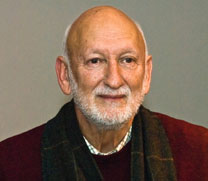

| Leonid “Leo” Feigin used to

be known as Alexei Leonidov founded the label Leo Records in London. Source: Press photo |

Soviet émigré Leonid “Leo” Feigin used to be known as Alexei Leonidov, head of musical programs for the Russian service of the BBC. In 1979, he founded the label Leo Records in London.

“It all began with a love of music,” Feigin says. “I was working at the BBC, but it was clear that I wasn’t being fully utilized; I wasn’t squeezing out all the juice. I would make a beeline to concerts nearly every night. After two or three years of living in London, I knew a lot of musicians personally. So, once, friends from Leningrad had Western tourists smuggle out a recording, and my friends said, ‘It’s a group from Lithuania, they conform to Western standards.’ ‘OK,’ I thought, ‘It’s some Ganelin, Chekasin and Tarasov.’ But I listened and was amazed — they weren’t worse than the best groups in the West.”

“I started offering their recording to recording companies, but no one believed me: Some sort of trio, there were three saxophones, keyboards, electric guitar, synthesizer and so on; about 15 instruments by their calculation. No one believed that there were such astounding musicians in the USSR. I couldn’t convince them, and I decided to release the trio myself,” the producer says.

“But I realized in time that, if I started a company with a release by this trio, again, no one would believe that such trios could exist. So I went to America and recorded the young singer-pianst Amina Clodine Myers and the famous avant-gardist Keshavan Maslak. And that’s how it all started — Leo Records, which does not release commercial music.”

“To be honest, the average person doesn’t really understand this music. It isn’t relaxing jazz. It’s new music, based on completely different philosophical and aesthetic principles, encompassing free jazz, free improvisation and avant-garde. Sometimes it’s called ‘open music,’ because it is not at all constrained; there are no musical or aesthetic restrictions, and it permits everything except cliché,” Feigin says.

The Soviet art that was released on Leo Records was pure contraband: Russian compatriots were barred from exporting paintings and manuscripts, not to mention audiotape. Leo’s contraband avant-garde received glowing reviews. The fruits of his efforts have been immense.

Musicians of an openly avant-garde genre that is “not for everyone” — musicians who lack wide recognition in Russia and could be monetized abroad — have released albums in the West and had success. Russian music broke the information blockade and the musical map of the world changed.

Feigin is not so much a businessman as he is a music-lover and romantic; he is not shy about discussing commercial difficulties and mistakes. The label was created in 1979, but “the debts, which were totally unreal, weren’t paid off until 1990,” he says.

Nevertheless, Feigin considers his own artists — geniuses of the anti-commercial genre, including Sergei Kuryokhin (the Russian celebrity and enfant terrible of the Russian avant-garde) and Anthony Braxton (the American father of free jazz) — many things, but not failures. In his opinion, others get sucked into avant-garde, winning financially but hopelessly losing in terms of the very content of the art.

“Musical avant-garde can be compared to a locomotive that pulls hundreds of cars. It’s an entire train of freeloaders: pop, rock, jazz, classical music. . . They all profit from the achievements of avant-garde!”

Until now, festivals of noncommercial and avant-garde music in Moscow have been an oddity. Avant-garde musicians have nowhere to play and nothing to lose, besides their social networks.

“The outlook for Russian musicians is a dire problem,” Feigin says. “Foreign musicians love coming to Russia. They may not earn much money, but they gain a lot more than money from such trips — specifically, a grateful and knowledgeable audience that is many times larger than their audience in the West,” says Feigin.

“But this is a one-sided exchange: It is hard for Russian musicians to break away to the West. The image of Russia is now so low that not a single Western promoter even tries to invite Russians. In the 1980s and 1990s it was possible; promoters invited musicians out of curiosity.”

“Now, with the Iron Curtain gone, interest has dropped. And everyone has somehow gotten used to the thought that Russia is a country of horrors, where there is nothing but corruption, oligarchs, riggedelections and suppression of freedoms,” the producer says.

“The second reason, of course, is financial. I released some albums by the duet Yevgeny and Anastasia Masloboev. They got excellent reviews. A few French promoters wanted to bring them to the West; but as soon as they found out that they’d have to bring the duet from Irkutsk, interest immediately disappeared. It’s very expensive!” Feigin says.

In Russia, there is not yet a system for supporting serious noncommercial art, while, in the West, this has already been thought out — particularly in small countries where musicians simply need to go perform abroad. This includes GEMA in Germany, PRS in England, Pro-Helvetia in Switzerland, and similar structures in Sweden and Norway.

“Everybody financially supports their own musicians. The monstrosity of the situation is exacerbated by the fact that, in Russia, there are more than a thousand billionaires, but their cultural qualifications are so low that it doesn’t occur to even a single one to somehow help music development,” Feigin says.

“And yet, even now, an impressive new generation of talented musicians is coming up in Russia — Alexei Kruglov, Alexei Lapin from St. Petersburg, Yevgeny and Anastasia Masloboev. They’re all great musicians — the young as well as the older ones, such as Vyacheslav Guyvroronsky, Vladimir Volkov and Arkady Shilkloper, a French horn player who is famous in Europe,” says Feigin.

“This is what is lacking in traditional jazz, in the mainstream. I feel the Russian soul in the new music.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox