Russian emigre life in 1920s Shanghai

|

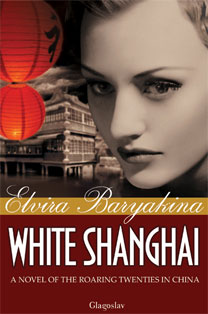

| "White Shanghai" tells several interlinked stories of families and individuals, washed up on the shores of the Huangpu River. Source: Glagoslav Publications |

After the Bolshevik Revolution, tens of thousands of Russians fled to Shanghai, which became Asia’s most cosmopolitan city.

Historical novelist Elvira Baryakina’s portrait of the roaring twenties in "White Shanghai" is a suitably bewildering kaleidoscope: prostitutes, bandits and fortune-telling Buddhist monks, warrior Cossacks and singing Mexicans. "Almost like Paris, New York, and Babylon combined," is how Baryakina described 1920s Shanghai in an interview with RIR.

One Russian émigré, a distant relative of Baryakina’s, told her about life in Shanghai: "It was a special world, something completely unique … But when the Japanese occupied the city, and later Mao exiled the white colonists from the country … old Shanghai disappeared forever." A lost city was an irresistible topic for historical fiction.

"I started from the very beginning, with textbooks on Chinese history," Baryakina said. "Completely by chance, in a second-hand bookstore I found a whole stack of pre-war memoirs by people who had lived in Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s" and, in the neglected library of an Orthodox church in Los Angeles, self-published autobiographies "written by Russians who had come over from Shanghai to America."

"White Shanghai" tells several interlinked stories of families and individuals, washed up on the shores of the Huangpu River.

"In those crazy days," said Baryakina, "China was a melting pot of imperialism, communism and the opium trade." Wildly different tales of struggle and survival divide and interconnect in the best traditions of epic Russian storytelling: "What would you do if you came there with no money and no documents?" Baryakina asked.

Hidden connections

One pivotal narrative concerns reporter, Klim Rogov, and his beautiful, cunning wife, Nina, who leaves him and sets up a fake embassy, the first of many enterprises.

In Baryakina’s prose, new inventions – instant coffee, toasters, cellophane wrap – run alongside fairytale motifs from various cultures.

The Russian witch Baba Yaga or the Japanese fox-temptress Kitsune reflects the characters’ shifts of fortune. "Are your crystal shoes not too tight?" Klim teases Nina, or are you dreaming about "finding the cave of Ali Baba?"

Baryakina’s characters are Czech, Chinese, English, Mongolian and many other nationalities, but the novel’s emotional trajectory follows the Russian refugees, first seen weeping farewell to the "distant motherland."

Baryakina quotes the adage that "Russia is a country with an unpredictable past," but insists that history is interconnected, like the lives of her characters: "My mission as an author is to show these hidden connections."

She sees particular parallels between Russian and Chinese history: "China adopted the communist ideology from Soviet Russia and I describe in my novel how it all started and why." There are also cultural connections, like the Chinese origins of Russian dumplings or samovars.

Details of food or artifacts can powerfully evoke homesickness or gaps between cultures and classes. After shipboard seaweed-bread, the menu from a French restaurant seduces Nina with its chestnut mash, roast pheasant, anchovy, truffles and wild saffron rice.

The new land of rickshaws and mah-jong is shadowed by the nostalgic charms of "autumn mushroom markets … wooden bathhouses and holyday chimes."

Visiting every location

"I know that most people don’t care about the little details, but they are dear to me. I don’t like reinventing history; I enjoy restoring it," Baryakina said. She spent several weeks in China, visiting every location mentioned in the novel: "There is not much left from old Shanghai … but the famous Bund [waterfront] is still there as well as Nanking Road, Astor House, the Russian Consulate building…"

One of Baryakina’s strengths as a novelist is a powerful sense of place, from a liaison in a spice shop, "enveloped by the smells of ginger and cinnamon," to the humped bridges, weeping willows and upturned roofs of Suzhou. "I really enjoyed the poetic city of Suzhou with its ancient houses and channels," the author said.

"White Shanghai" is one of a series of novels about wars and revolutions. Baryakina relishes historical paradoxes and migrations.

"Vanished Russia," the prequel to "White Shanghai," centered on a Russian journalist who made his career in Argentina and returned in 1917.

She recently turned her attention to a "community of foreign journalists in Moscow at the beginning of Stalin's Era," who enjoyed unusual luxuries, but also "witnessed the birth of the totalitarian state at its worst." Her next novel concerns "international immigrants living in Berlin … swept away by the Great Depression and the Nazis."

Feminists and flappers

Many of the most compelling characters in "White Shanghai" are women, from materialistic Nina, to Ada, the orphan girl, who dances in a brothel, escapes to work as a governess, and dreads a return to that "smoky, lecherous world."

The novel features several journalists, including American reporter, Edna Bernard, with her books by Darwin and Emmeline Pankhurst.

The endemic sexism and incipient feminism of the age are recurring themes. Edna’s unhappily married sister, Lissie, spends her days reading about aristocratic divorces and mysterious murders; she decides to start a women’s magazine for the freedom-loving, flapper generation, announcing "young women aren’t happy to be ornaments for males anymore."

Baryakina has produced an interesting, complex novel, which occasional lapses in translation and editing cannot spoil. The evocations of place and time are mediated through a feel for the lives of individuals in unsettled times. The elegant illustrations are deliberately reminiscent of 1950s fiction.

"I tried to write my first historical novel when I was in high school," she said. "When the Soviet Union collapsed I started to ask my first ‘whys’ ... I wanted to know what had happened to my country, but soon I realized there is no single country’s history. All states and nations are interconnected."

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox