Best books from Russia in 2013

2013 was an excellent year for books by Russians and books about Russia. Source: Getty Images/Fotobank

|

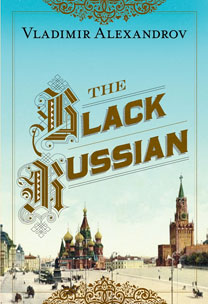

| 'The Black Russian' by Vladimir Alexandrov, Atlantic Monthly, 2013) |

One of this year’s most remarkable true stories is Vladimir Alexandrov’s compelling account of the life of the American expatriate Frederick Thomas. “The Black Russian” tells the unknown saga of Thomas, the son of former slaves who became one of Moscow’s richest entrepreneurs of the early 20th century.

The eminent literary critic, editor and professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., commented that “The Black Russian” is an amazing story, and that Thomas’ “improvisational life…filled me with wonder.” Gates concluded, “His story staggered me.”

Alexandrov, a professor at Yale University, spent years hunting through what the author called “a labyrinth of archives and libraries in five countries”.

|

| 'Pushkin hills' by Sergei Dovlatov, Alma Books, 2013 |

He vividly retraces Thomas’s extraordinary adventures from the poverty of 1870s Mississippi to his flamboyant empire in turn-of-the-century Moscow and beyond.

The resulting picture of a charming, ambitious businessman, daringly reinventing himself in numerous countries, fleeing the Bolsheviks and pioneering jazz, would make a gripping movie biopic (Atlantic Monthly/Grove, NY, March 2013).

This year was an excellent one for books by Russians and books about Russia. Douglas Smith’s “Former People,” a compassionate portrayal of the post-revolutionary fate of the Russian aristocracy, has garnered high acclaim; Sergei Dovlatov’s late Soviet classic, “Pushkin Hills,” was published for the first time in English, and several publishers continue to deliver high-quality translations of familiar and emerging Russian novelists.

|

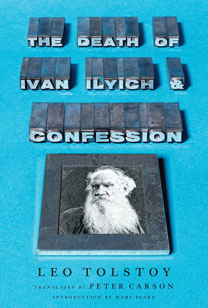

| 'The Death of Ivan Ilyich' by Leo Tolstoy, Penguin Books, 2013 |

Hot off the press in the United Kingdom and forthcoming in the United States, Leo Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich” and “Confession” appear in a new translation by Peter Carson, the former editor-in-chief of Penguin Books, who died earlier this year. Carson spoke Russian at home with his mother, Tatiana Staheyeff and translated works by Chekhov and Turgenev for Penguin. His great-grandmother built the dacha where the poet Marina Tsvetaeva later spent her final days. His own last days were spent translating Tolstoy’s unflinching meditation on mortality “The Death of Ivan Ilyich.”

Deliberately simple language reinforces the bleak and claustrophobic “consciousness of approaching death.” The screaming horror and stench are tempered by Tolstoy’s glimmering sense of redemption. Carson insisted that it should be published together with Tolstoy’s strange piece of spiritual autobiography “Confession,” whose themes it illuminates and the pairing presents an intimate portrait of the great novelist. (W.W. Norton, London, October 2013 and Liveright, New York, November 2013).

|

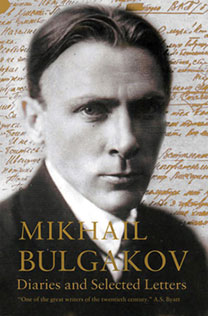

| Diaries and Selected Letters' by Mikhail Bulgakov, Alma Classics, 2013 |

A first full English translation of Mikhail Bulgakov’s “Diaries” together with “Selected Letters” arrived this summer from Alma Classics. The Soviet authorities confiscated Bulgakov’s diary in 1926, when he switched to letters. His account of near starvation and a “chaotic … nightmarish” existence “in a totally disgusting room” contradicts the approved reports of Utopian, communist life.

This volume, covering 1921 to his death in 1940, illuminates not only the writer’s Moscow years, but also the historical era. The weather, politics and even the inflation are all detailed here along with Bulgakov’s own difficult literary progress. His letters to officials make particularly fascinating reading. “A wolf may have his skin dyed or be shorn, but he’ll never be a poodle,” he wrote to Stalin in 1931, pleading for the chance to be stay true to his own unique creativity. (Translated by Roger Cockrell; Alma Classics, June 2013).

|

| 'An Armenian Sketchbook' by Vasily Grossman, NYRB Classics, Maclehose, 2013 |

Translator, Robert Chandler, brought Vasily Grossman’s work to western audiences in 2006, with his version of “Life and Fate.” This summer, Robert and Elizabeth Chandler’s translation of Grossman’s “An Armenian Sketchbook” shows us the author in a new light. This relatively light-hearted travelogue, written in 1962 after two months in Armenia, is a total contrast with his epic novel about war and totalitarianism.

From his first train-window glimpse of stony fields and flat-roofed houses to his final impressions at a village wedding, Grossman’s emotional memoir celebrates “kindness, purity, merriment and sadness.” He aims to bring together the “truth of the eternal world” with a more personal, human reality.

“An Armenian Sketchbook” would make an ideal gift, especially with James Nunn’s attractive cover design for the U.K. edition. (NYRB Classics, Feb 2013 and Maclehose, July 2013)

|

| 'Murder at the Dacha' by Alexei Bayer, Russian Information Services, 2013 |

New York based author, translator and economist, Alexei Bayer, made the jump from short stories to full-length fiction this year with his Soviet-era whodunit, “Murder at the Dacha.” Pavel Matyushkin, a motorbike-riding police officer with a complicated love life, has a murder mystery to unravel. As the title hints, the story revolves around a cottage in the forest, but is mostly set in 1960s Moscow. There are moments of courtroom drama, labyrinthine corruption and a meandering Russian-style plot. Bayer, who has produced English and Russian versions of his own book, draws on both cultures: “It was a lot like the final scene in Gogol’s play, when the true Government inspector is announced,” he says of a dramatic pause.

A more contemporary Moscow is revealed in one of 2013’s best new novels in translation, Andrei Gelasimov ‘s “The Lying Year,” which satirizes the lives of Russia’s new rich. Mikhail Vorobyov’s old boss hires him to look after his teenage son, Sergei, whose own diary entries describe the pain beneath his pampered life. He charts death, abandonment, infidelity and isolation, in a heartbreakingly simple style, laced with the violent, suicidal impulses of youthful disaffection.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox