The wonders of the Russian izba

Today, the izba is no longer the main type of Russian dwelling, but its legacy lives on in Russian consciousness. PhotoXPress

How can you sleep on a stove and not get burned? Why is there a knife stuck in the doorpost? Where does the house spirit reside, and how are the icon corner and the chicken head connected?

In a Russian izba, these traditions and superstitions are essential to life.

Although most Russians now live in modern flats, every Russian still knows what an izba is. Izba, a traditional log hut and the main dwelling type for Russian peasants, is widely featured in folklore. Baba Yaga, the archetypal Slavic witch, lives in her izba that stands on chicken legs.

Epic hero Ilya Muromets spent 33 years of his life in an izba, lying on a stove, before going away to save the land from evil.

At the same time, an izba was a real dwelling, usual for many generations of Russians, just as our flats are for us now. But the story of an izba can tell a lot about Russian life.

Sacrifices, horse`s head and animal skins

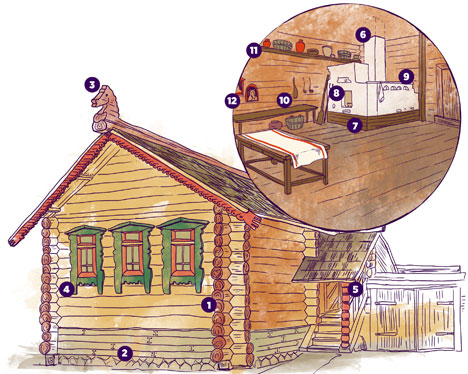

Log house with a two-sloped hay roof and windows in the front – that’s the classical look of a Russian izba.

Click to enlarge the infographics

The building of an izba traditionally began with a sacrifice: according to pagan beliefs, a life must be taken upon the building of the house, so usually a chicken’s head was chopped off and placed under the main corner.

Nowadays in the cities, the ritual still exists in mild form — a cat must be the first creature to enter a new flat. Some families even borrow cats for this occasion.

As stone was scarce in Russia, izbas were made of pine or spruce wood, and not birch, a tree that is abundant in Russia. This was because people living in birch izbas became nauseous, slept unwell and even lost hair. Izbas often had no base, just a wooden floor, except for the swampy regions, where trees’ stumps were used as base – it’s these stumps that look like “chicken legs” of Baba Yaga’s hut.

Where to visit a real izba?

In Russian villages, there are very few old izbas left. But you can visit the preserved 19th century izbas in several museums of wooden architecture. The “Malye Korely” museum (located 15 miles from Arkhangelsk) presents tours and lectures on the northern Russian architecture.

There are also museums in Nizhny Novgorod, Suzdal and Kostroma. In Moscow, the Museum of Wooden Architecture is located in Kolomenskoye estate. Here, you can see rural houses, a wooden fortress with gates and towers, and a 17th-century wooden church.

A two-sloped roof covered with hay was also a distinctive feature of an izba. The front end of the roof’s ridge was often shaped as a horse’s head. Windows were first just ventilation openings in walls, covered with boards or animal skin – only in 18th and 19th centuries, “red” (i.e. “beautiful”) glass windows with decorated jambs started to appear.

These windows were made in the front wall of the izba, which faced the street. Under the windows, on a bench, beautiful country girls and babushkas used to sit in the evenings, spinning yarn, eyeing passers-by and spreading the village gossip.

The door of an izba usually was in the sidewall or in the back. For Russians, the door has always been a portal between the “inner” and the “outer” world. To this day, Russians do not shake hands or pass things over the threshold, try not to look inside the apartment through the doorway, and so on.

Threshold and doorjamb were places of high occult importance — that’s why a blade or a nettle leaf could be tucked into the doorpost, to protect the house from spirits and witches.

Saints and spirits under one roof

A typical izba only has one big room, approximately 265 square feet, where peasants cook, eat and sleep, and the central object inside is the stove. The very name of izba comes from the stove: in early Russian, izba meant “the one being heated.” Stoves made of brick or clay were placed on a separate base, so that the house wouldn’t lean to its side. Inside the stove base, dishes and cookware were stored.

A old Russian stove had no cooking range on top — it was a heating device that doubled as an oven. It needed to have a large mass, since it was fired only once a day in the morning and then worked as a heat capacitor for the rest of the day.

In the evening, the stove was still comfortably warm, so its top was used as the coziest sleeping place in the izba. Who could occupy this place? Maybe, a grumpy grandfather, who, even if too weak to work, would govern the whole family as the elder, proving his point with a stiff wooden stick.

In winter the inside of the stove doubled as bath — it was spacious enough for a grown man to fit in. The stove was also the place where domovoi, a Russian house-spirit, was believed to reside. He preserved peace and abundance in the family, and so had to be pleased and ritually fed, but was still considered unclean, which is why the stove was placed opposite to the icon corner.

In this corner, icons and icon-lamps were placed upon the shelves below the ceiling. Under the icons was the father’s place on the bench at the family table. Nobody could start eating before the father started, for he’s the one who provides for the family. As for gramps, he will be brought food right to his berth on the stove.

In most izbas, there were up to 10 inhabitants, so it was enormously crowded. At night, the benches doubled as sleeping places, since there was little or no place for a bed. The children could sleep on boards set above the stove, called “polati.” Peasants slept under felt covers, heads towards the icon corner, and pillows were a luxury.

Only in the second half of the 20th century did bed blankets appeared in all Russian country houses. By that time, electricity was brought to the countryside; radio and TV have replaced distaffs and Bible readings as means of spending time; and portraits of Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, were pinned to wooden walls of the old izbas.

Today, the izba is no longer the main type of Russian dwelling, but its legacy lives on in Russian consciousness. “Let’s hit it right from the stove,” Russians say when they want to start something from the very beginning.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox