Triumphs and tragedies of Russia’s hippies

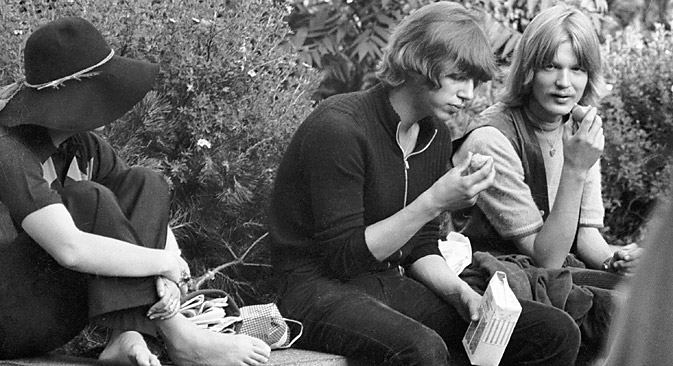

In 1971, there were about a 1,000 hippies in Moscow. Source: Lev Nossov / RIA Novosti

On June 1 of every year, the Russian capital's hippie community congregates under a tall solitary pine — which everyone calls an oak, for some reason — to remember tragic events of 40 years ago.

In 1971, there were about a 1,000 hippies in Moscow. They used to gather at such favorite haunts as "the Psychodrome” near the old building of Moscow State University; "the Square” outside what is now the Moscow mayor’s office, near the Yuri Dolgorukiy statue; beside the Pushkin memorial; and at an underground pedestrian crossing on Gorky Street, which has since been renamed to Tverskaya Street.

On May 28, 1971, each of these places was visited by plain-clothed KGB officers. After presenting their KGB credentials, they invited the hippies to stage a protest against the Vietnam War outside the U.S. embassy in Moscow.

Smart people in the Soviet government were asking for their help in fighting American militarism, the hippies were told. It was agreed that on June 1, Moscow’s hippies would gather at their usual spots with anti-war slogans, and that the plain-clothed people would take them to the embassy and organize the whole protest.

As agreed, on June 1 the hippies turned up with their pacifist slogans. Several busses arrived; the unsuspecting hippies were invited to get in, which they did. The busses then trundled off, but not to the U.S. embassy. Their destination was police stations.

The name of each passenger was recorded in a voluminous book with the word HIPI written in large letters on the cover. Everyone whose name was recorded then had his or her entire lives destroyed, as part of a deliberate and methodical campaign.

Of the 500 people detained that day, about half were sent to serve with the Soviet forces on the Chinese border. A hundred or so were clamped into psychiatric hospitals. Dozens were jailed on various charges.

Two died while serving in the Army. Another two died in a nuthouse. Two hanged themselves. Those who survived effectively became unemployable. The government hoped that was the end of the Russian hippies. It was wrong.

Dmitry Akhtyrsky, philosopher, former lecturer at the RGGU humanities university:

“The hippie movement is part of Western culture,” said Akhtyrsky, who recently emigrated to New York City.

“The people who join that movement become essentially Western people, even if they have an interest in Oriental things. They often refuse to identify themselves as hippies. If you ask one of them who they are, they will say, ‘I’m a person.’ If you ask them if they are a hippie, they will often deny it. Many of them are not eager to display any external attributes of being part of the hippie movement. But, as a rule, they still have some distinguishing features, such as long hair. For me, that hair is like a medal awarded to me in memory of non-violent resistance to cops, thugs, and the establishment. I have been known to dress up in a suit and wear a tie for hippie parties, and to deliver lectures at the university in torn jeans and sporting friendship bracelets.”

Andrey Oleynikov (Alkhemist), a perfumer and expert on poetry and philosophy of the Silver Age:

The Alchemist first came to “the Square” in the early 1970s. He was barely 17 at the time. Brought up in a well-off family, he is a typical member of the Russian intelligentsia. His conversation is sophisticated, almost aristocratic, and his intonations Chekovian, with hippie slang words showing up in unexpected places every now and then.

Andrey Oleynikov (Alkhemist). Source: Konstantin Salomatin / SaltImages

“A friend of mine and myself decided to pass a kind of initiation ceremony,” said the grizzled Alchemist.

“We wanted to set ourselves apart from the reality that surrounded us. So we took our shoes off, and proceeded to walk barefooted along the street. Naturally, the police took us. They brought us to the station, but then, unexpectedly, released us. Later that day, we were sitting at an organ concert at Tchaikovsky Hall, wearing our extravagantly torn hippie outfits. That was a wonderful adventure.”

One of the central elements of the flowerschildren’s mythology is the myth of the hippie system. It is believed that the myth was created in the late 1960s by one Solnyshko (Sunny), known to the rest of the world as Yuriy Burakov.

Chronologically, there have been three different systems. The first lasted until the early 1970s; it relied heavily on alcohol and less so on intellect. The next system emerged in the late 1970s; it was more intellectual, but it soon collapsed under the strong influence of Orthodox Christianity.

The final iteration of the system arrived in the mid-1980s, but it, too, succumbed to Orthodoxy, which seemed to offer refuge from all the vices of freedom, such as drugs and loneliness, and, eventually, from freedom itself.

Conversation at the hippie parties soon degenerated to discussing long lists of the dearly departed. Many of the formerly prominent members of the hippie community ended up throwing themselves out the window, or dying in a nuthouse, or giving themselves a fatal drug overdose.

One Krasnoshtan (Red Pants) turned into a hobo; someone beat him to death with a stick in an alley off the Arbat. Volodya the Psalm Singer became a cocaine dealer; he ended up with 33 knife wounds, and died on the spot.

Yan the Death Dealer lost his marbles; he poured petrol on his best friend and lit up a match. He died in prison.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union the System left the real world and moved to the virtual one. It now exists in the narrow confines of Internet chat rooms and social networks. It's a separate world, which is open but almost inaccessible to those who don’t need it.

The hippies are now nearly indistinguishable from the rest of the urban crowd. Their numbers are estimated at 1,000 in Moscow, and perhaps 5,000 in the whole of Russia. But the figures are more of a guesstimate; counting the hippies is an impossible task. Apart from those who identify themselves as hippies, there is a whole army of those who don't, but who are real hippies nonetheless.

First published in Russiain in Ogonyok magazine.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox