Love and kindness in the age of terror

|

| Source: amazon.com |

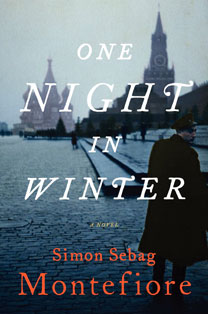

Historian Simon Sebag Montefiore’s new novel “One Night in Winter” centers on a real event: a dramatic murder-suicide in 1943 involving children from elite Soviet families. Sebag Montefiore, famous for his biographies of Stalin, mentions the story in his “Court of the Red Tsar”. In the new novel he transposes it to 1945 and invents a huge cast of new characters.

Students in one of Moscow’s schools for children of party elite form a “Fatal Romantics Club”, inspired by Pushkin. They reject the suffocating, “philistine world of science and planning, ruled by the cold machine of history” and pledge themselves to love or “if we cannot live with love, we choose death.” Andrei is the son of an exiled “enemy of the people”. He is drawn into this club whose “Game”, based on Pushkin’s duel, will end in disaster.

There are echoes here of “Dead Poets Society” or of Donna Tartt’s “The Secret History”. But the novel segues from Potteresque school story to harrowing interrogations in Lubyanka. Andrei’s mother warns him about the perils of making friends among the elite offspring: “Factions are dangerous. Remember whose children they are.” She has taught him to live carefully, with the neurotic anxiety engendered by Soviet life: “never speak your mind.”

Coded messages are a recurrent theme. “These days everything … was in a hieroglyphic code. Nothing quite meant what it said.” Lovers communicate via bookmarks hidden in library copies of Galsworthy, Edith Wharton or Hemingway. An imprisoned ten-year-old must work out how to answer his interrogators - “Was Pushkin, in this case, national poet (good) or romantic nobleman (bad)?” - and ultimately which parent to betray.

The novel explores powerful attachments of many kinds: to land or lover, sibling or spouse. Family ties are central as is the “warmth of kindness” in an age of ice. “We need food and light scientifically – but none of it matters without love,” one of the teenagers tells his politburo father. Sebag Montefiore writes in his endnote: “This is not a novel about power, but about private life – above all, love”. It is also, inevitably, about death: “every love story’s a requiem,” the heroine Serafima learns.

Sebag Montefiore has a historian’s panoramic overview. Andrei reflects that: “No grand duke of the old days … could equal the sneering haughtiness of a Communist prince.” The dynamics of Stalin’s merciless reign are informed by authentic details, like his admiration for Ivan the Terrible: “Don’t just show that Ivan was cruel … show why he needed to be cruel,” Stalin says in a message for Sergei Eisenstein, director of “Ivan the Terrible”, a state-approved biopic of the first Russian Tsar.

This is a stronger, more convincing novel than Sebag Montefiore’s first foray into fiction. “Sashenka”, published in 2008, was a sensationalist story about a revolutionary teenager. “One Night in Winter” acts as a kind of sequel with a second appearance from some characters, including charismatic Benya Golden, who has survived the gulag and become a teacher. There are ongoing explorations of individual resilience and complicity: “you, like millions of others, had no choice,” Serafima says towards the end.

As an entertaining story with a thrilling backdrop, Sebag Montefiore’s novel is an appealing, historical romp, which achieves his aim, as stated in “Sashenka”, of making “these strange and tragic times in Russian history interesting for readers who perhaps wouldn’t read history books.” But, as a more profound exploration, it occasionally rings hollow, despite its flirtation with the horrors of Stalinism.

Russian writer Alexander Terekhov’s acclaimed postmodern masterpiece,“The Stone Bridge”, published in 2009 uses the same teenage deaths of 1943 as its starting point. Terekhov also chases historical mysteries and mixes fact and fiction, but the aim and atmosphere of the two novels could not be more different. For Terekhov, history is an impassable wasteland in which explorers perish. For Sebag Montefiore, history – even at its bleakest – is a landscape for romantic adventure.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox