How the USSR aided D-Day

British Navy Landing Crafts (LCA-1377) carry United States Army Rangers to a ship in Southern England. Source: UllsteinBild / Vostock Photo

The retired Royal Navy cruiser the HMS Belfast fired its six-round salute at midday on June 5 in London to mark the 70th anniversary of the assembly of the D-Day fleet, beginning the commemoration of one of the key battles of World War II, an amphibious assault that remains the largest the world has ever seen. The Belfast, which is now preserved as a museum, fired one of the opening salvos on June 6, 1944, attacking a German artillery position at La Marefontaine, supporting British forces landing on Gold and Juno beaches.

On June 6, U.S. President Barack Obama, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, will join veterans from the U.S., the UK and Canada in Normandy to mark their contribution to the defeat of fascism in Europe. Alongside them will be Russian President Vladimir Putin, and while no Soviet forces took part in the amphibious operation itself, his presence there is apt, given the enormous part Russia played in the success of Operation Overlord.

The air supremacy enjoyed by the Allies on D-Day and crucial to its successful outcome owed much to events on the Eastern Front. The combined Allied air forces flew 14,000 sorties in support of the D-Day landings and met with fewer than 100 German ones in response, an overwhelming superiority.

Moreover, in the months preceding D-Day, the Allied air forces had been free to disrupt utterly the arrival of German reinforcements. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, in charge of the German defenses of Northern France, desperately wanted Ju 87 Stuka dive bomber units to defend the Atlantic Wall, but was denied them by Hitler who insisted they remain on the Eastern Front.

American equipment has arrived on Omaha Beach. June 1944. Source: UllsteinBild / Vostock Photo

The situation in the air was mirrored by events on the ground. Two-thirds of the Nazis’ available manpower was tied up fighting on the Eastern Front. Given the huge resistance encountered, particularly by U.S. troops on Omaha beach and the fierce fighting which followed, notably in Falaise, it’s clear that had the D-Day landing force encountered anything like the full strength of the Wehrmacht, the outcome of the battle could have been very different.

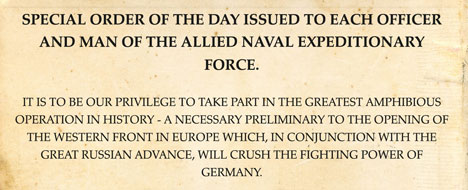

Perhaps inevitably, given the rapid post-War cooling of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and the West, the Red Army’s role both in the success of the D-Day landing and the outcome of the war itself was drastically underplayed. But, as one document being displayed on HMS Belfast at the June 5 celebration makes clear, not everyone in the West was unaware of the Russian sacrifices.

That document is the special order of the day issued to each officer and man of the Allied Naval Expeditionary Force by Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay ahead of the assault. It begins: “It is to be our privilege to take part in the greatest amphibious operation in history, a necessary preliminary to the opening of the Western Front in Europe which, in conjunction with the great Russian advance, will crush the fighting power of Germany.”

Captain Leigh Merrick, who joined the Royal Navy in 1965 and served as a naval attaché in both Moscow and Kiev, believes that Ramsay’s order reflects a wider truth about the officer corps.

“Navies tend to be very au fait with the international situation by the nature of the fact that they are global, more so perhaps than their sister services,” Merrick said. “This is a wonderful example of just that. Ramsay was the only one of the senior commanders to refer to the Russians’ efforts.”

For Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, who had been looking to the Allies to open up a second front since 1942, the D-Day landings, although later than desired, provided much-needed relief. Once Germany was forced to repeat its experience of World War I and fight a campaign on two fronts, the outcome of the war was all but inevitable. Indeed, just two weeks after D-Day – with Hitler forced to commit 168 divisions to counter the threat from the West – the Red Army launched Operation Bagration, the biggest Soviet offensive of the war, to take out the German Army Group Centre on the Eastern Front.

Although immeasurably less well-known in the West than D-Day, the scale of Operation Bagration dwarfs the Normandy landings with the Red Army mustering 10 times the number of men who fought for the combined Allied forces in Normandy.

D-Day, Operation Overlord, Omaha Beach: American troops of the V Corps leave the landing craft 326, June 7 or 8, 1944. Source: UllsteinBild / Vostock Photo

It was a stunning success, with Russian forces taking their German foes by surprise and rapidly recapturing all of the land lost in 1941 and even moving into Poland and East Prussia with the resulting annihilation of Hitler’s Fourth Army, Third Panzer Army and Ninth Army.

And while it is impossible to overstate the courage of the Allied men who stormed the beaches of Normandy under heavy fire, it’s also worth remembering that different, more brutal, rules applied to the conflict in the East.

In Das Reich, his peerless account of the 2nd SS Panzer Division’s march through France in 1944, Max Hastings quotes the shocked reaction of German tank officer, Fritz Langanke, on witnessing a temporary ceasefire in Normandy to allow both sides to retrieve their dead and injured. “In Russia,” Langanke said, according to Hastings, “we would have driven straight over them.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox