Remembering the last hero of Russian rock

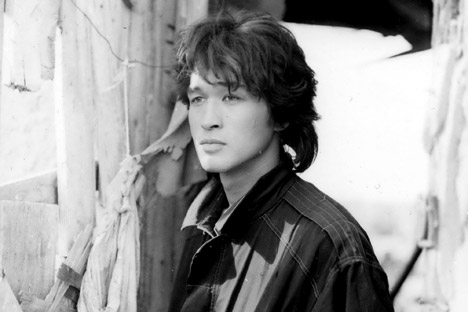

Viktor Tsoi in a scene from "Needle. Remake" film. Source: ITAR-TASS

It is almost 25 years since Viktor Tsoi, the frontman of the group Kino, died in a tragic accident. Yet Tsoi, who is the only rock star who is recognized on a national scale, continues to be the principal avatar of Russian rock music. He was the only musician who was able to capture key aspects of everyday life – war and love – in Russian in a way that is still remembered by everyone.

Portrait of the artist as a young man

Viktor Tsoi was born in Leningrad in 1962. While his mother was Russian, his father was a “Russified” Korean. As a child, Tsoi exhibited a talent for drawing. To make money, he painted portraits of Western rock stars such as Robert Plant with ink and sold them on the black market. Tsoi taught himself how to play guitar and started writing his own songs at a young age. Later, he formed a band called Kino: a quartet that sounded similar to Joy Division, The Cure, and Tsoi's favorite – The Smiths.

Kino started off as an underground band with almost no chances of making it big. Nonetheless, Tsoi and his friends, like all underground rock musicians, recorded albums and circulated them on tape reels. “Original” recordings (i.e. second copies of the master tape, with artwork) sold for ten rubles - the price of three bottles of vodka. Then the “album” was recorded from one tape player to another. This process, known as “magnitizdat”, was the audio analogue of “samizdat” (self-publishing) in literature.

Folk songs

Interesting music quickly spread throughout the country, from Moscow to Vladivostok, bypassing official structures. This was what happened to one of Kino's most powerful albums, Gruppa Krovi (1988). At the time, the album could be heard on just about every tape player in Russia.

Hit songs, trendy electronic sounds, almost danceable rhythms: Nobody in the country made the same type of music. A year before the tape came out, a film by one of the state’s officially sanctioned directors, Sergei Solovyov, called Assa premiered in movie theaters. The film had an unexpected ending: a live performance by the band Kino. Kino performed a song with the refrain “We are waiting for changes” (“Mi zhdem peremen”), which became the unofficial anthem of perestroika. It is interesting to note that the song was unrelated to politics and actually told the story of a teenager dreaming about adult life.

Source: Youtube / thatMikhail

Unlike other heroes of Russian underground rock music, he sang as if there had been nobody and nothing before him; as if he was singing for the first and last time. He was a figuratively naked person who inhabited a naked earth in a realm devoid of cultural context. Earth, sky, stars, sun, death, love, summer: these are the driving words of his songs. The context has died, changed and sunk into the past, but the words spoken by Tsoi ring true to this very day.

Then, in 1988-89, Tsoi became “everything to everyone.” In those days, just as now, it was common for teenagers to ask “What kind of music do you listen to?” when meeting each other for the first time. Although the answer was typically either “our music” or “foreign music,” Tsoi was the only artist who transcended all divides in musical tastes.

According to Tsoi's friends, he was no rock star in his everyday life. He was quiet, mediocre at telling jokes, and preferred doing sports to living a rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle (karate, for example).

Musicians against matryoshka dolls

In 1988-89, Kino were invited to perform abroad in Denmark, France, and Italy. By the way, it was in France that Tsoi launched his western recording career. The band re-recorded some of their songs, which were released under the album title Le Dernier des Heros (The Last Hero). It was a hit locally, but unfortunately the project didn't go any further.

Tsoi performed only once in the U.S., after the screening of the film Needle at Park City, where the film was shown as an out-of-contest entry in the Special Event category. Tsoi and the band's guitarist Yuri Kasparyan came to the premiere and played a short set after the screening. This was Tsoi's first and last visit to the United States. In an interview, Tsoi said, “Nobody knows who I am there, I can walk around on the street undisturbed.” The record was released on a small indie label called Gold Castle Records, and Village Voice published a positive review.

Judging by the interview, Tsoi did not believe that Western and Eastern audiences had a genuine interest in Russian rock music. He “couldn't turn down” touring in Denmark, because it was “a charity event.” He was clear about his opinion regarding France in an interview with the newspaper Young Leninistin the spring of 1989: “Russia is a popular theme in France right now, in terms of Soviet memorabilia and stuff like that. But there isn't really a serious approach to Russia, we’re like matryoshka dolls to them: ‘Hey, look, Russians can play guitars almost like we do.’

“A lot of bands have taken the opportunity to tour abroad, consciously accepting the fact that they will be touring on bad terms in terms of both pay and concerts. I didn't want to be a matryoshka doll,” said Tsoi. “The problem isn't so much the money, it's the prestige of the country. If you want to go abroad, it's best to go as a tourist.”

“For our part, we did make an attempt to take a different approach. First of all, we started by releasing a record in France. Second, it was a very well-known rock festival in Europe. This is why I decided to go and see if establishing a line of communication would be possible. I can't say it was a huge success, because people were expecting something Russian and exotic from us, and we delivered rock music.”

A star among stars

Tsoi died in a car accident in 1990 when he was 28 years old. The Kino concert that took place at Luzhniki Stadium in June of that year turned out to be the group’s last. It was sold out. “For the most part, it doesn't really matter to me where I'm playing: my apartment, an underground club, or a concert hall with 10,000 people,” Tsoi insisted. “If I have an opportunity to play, I play. If I don't, I am ready to play free of charge. Right now I have an opportunity to play for big crowds. I'm taking advantage of this opportunity, but I know it won't last forever. Either way, I'm doing what I love. Of course, I'm doing it so long as the circumstances allow me to, including the political climate in the country.”

It has been almost 25 years since Viktor Tsoi passed away. A lot of new music has come and gone since his death, many new stars have appeared and faded, but thousands of people of different generations continue to listen to Kino. It doesn't get old. Russia has many good musicians, but the country only has one rock hero. His name is Viktor Tsoi.

American Joanna Stingray, who first came to Russia as an independent traveler in 1984, instantly fell in love with Russian rock ‘n’ roll and decided to introduce Russian music to Americans. Within two years Stingray released the album Red Wave: 4 Underground Bands from the U.S.S.R., featuring Petersburg bands Akvarium, Kino, Alisa and Stranniye Igry (Strange Games). Stingray, who released five personal albums during her life in Russia, married Yury Kasparyan, the Kino guitarist, in November 1987. In 1989 Tsoi and Kasparyan went to the U.S. with Stingray. During those two weeks they ride in a limo, on horses and snowmobiles, went to see the ocean, Las Vegas and, finally, Disneyland, where Tsoi kept repeating that he felt like a child again.

Prepared by Tatiana Shilovskaya

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox