Monarchs' menu: Feasts fit for Russian tsars and emperors

Ivan the Terrible was radical in his cuisine. Source: Kinopoisk.ru

Little is known about meals that were served to Ivan the Terrible, one of the most eccentric Russian

"Lunch would last three or four hours," von Herberstein wrote about meals at the tsar's palace. "During my first mission to Russia, we even ate till after midnight… The tsar often treats his guests to food and drink…"

A more detailed description of a royal meal can be found in a historical novel by Aleksei Tolstoy called "Prince Serebrenni": "Once the swans were eaten, servants, in pairs, left the chamber and returned with three hundred fried peacocks… The peacocks were followed by

The next change of dishes was even more impressive: "The tables were laid first with meat jellies, followed by cranes with spicy herbs, marinated roosters with ginger, bone-free chicken, and duck with cucumbers. Then there came different soups and three varieties of

The tsar treated his guests only to classical Russian dishes of the time. For example, a

The filling of a chicken pie (called "

A meat jelly (also known as aspic) is a cold jelly made of meat broth with finely chopped meat inside; while an ukha is the traditional Russian fish soup.

Culinary pragmatism

The first Russian emperor, Peter the Great, was a man of modest tastes. One of his close associates, a mechanic and a sculptor, Andrey Nartov, recalled: "Peter the Great did not like any

Peter the Great liked the traditional Russian kvass

Open sourcesAnisette, which Peter the Great so

Taste of Enlightenment

Catherine the Great had the reputation of one of the

|

| Catherine the Great. Source: Press Photo |

Of sweets, she preferred the famous Kolomna

However, during official

The empress and her guests were served a dozen soups,

This is not at all surprising since, during Catherine the Great's rule, it was fashionable among the Russian nobility to hire French chefs and Russian cuisine was changing under their influence.

Those strange Russians

To an unprepared foreigner, Russian tsars' menus often seemed puzzling. One historical anecdote tells the story of how a Russian tsar sent a Western European counterpart of his a pound of black caviar and the European monarch, out of ignorance, instructed his cooks to boil it first. An English ambassador to the court of Alexander I once found himself in a similar situation.

The tsar liked discussing gastronomical topics with him and once, as a follow-up to a discussion they were having, presented the ambassador with

The ambassador, thinking that "those strange Russians" have sent him a soup that has grown hopelessly cold, ordered it to be warmed up, unaware that this Russian specialty should be consumed only cold. Having said that, not all foreigners showed themselves so ignorant when it came to Russian cuisine. For example, the legendary French cookery specialist and author Alexandre Dumas Sr. described the

Under 50 minutes

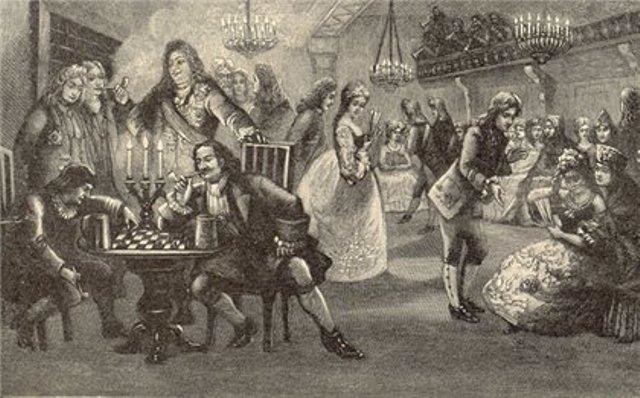

Mihály Zichy. The gala dinner in the Concert hall of the Winter Palace, 1873.

Open sourcesThe task was made all the more challenging because the tsar from time to time changed the venue for these family meals, with some of them being so far from the kitchens that staff found it extremely difficult to get all the food on the table

In the end, they came up with the idea of using large hot water bottles to keep the food warm. The trick did not always work with delicate sauces, whose original taste and

Alexander II's son, Emperor Alexander III, was much less of a pedant and remains in royal culinary history as the

According to the head of staff at the Imperial Court Ministry, Aleksandr Mosolov, "under Alexander II, all served wines were foreign ones. Alexander III started a new era for winemaking in Russia: he ordered serving foreign wines only when there were foreign monarchs or diplomats present at the meal. Otherwise, all served wines should be Russian. I remember that many officers found this wine nationalism misplaced: instead of assemblies, they began eating in restaurants, which were not obliged to follow the monarch's instructions."

However, soon attitudes towards Russian wines changed: largely thanks to the efforts of Prince Lev Golitsyn, who set up the famous wineries Massandra and Novy Svet. Gradually, Russian wines ceased to be seen by the Russian nobility as an oddity.

Last menu

The best chronicled in history are the culinary preferences of Russia's last tsar Nicholas II. Here is, for example, what Aleksandr Mosolov says in his book "At the Emperor's Court": "Lunch [at the Livadia summer palace in Crimea] began with a soup with small vol-

The Romanovs at the breakfast, 1910

Archive PhotoAll this was cooked by the emperor's favorite chef, Frenchman Pierre Cubat. Alas, after the 1917 revolution, French influences on imperial cuisine became a thing of the past. As did imperial cuisine itself, to be replaced by a Soviet culinary era.

Read more: The Kremlin diet: From Lenin to Gorbachev>>>

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox