The final days of Russian writers: Marina Tsvetaeva

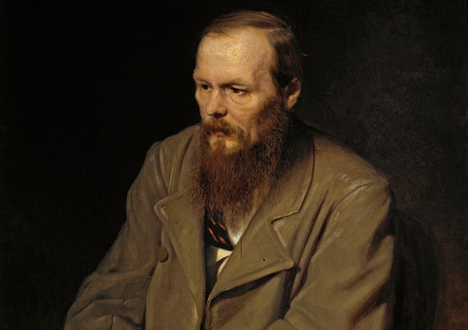

Poet Marina Tsvetaeva in France. Source: ITAR-TASS

Born in 1892, Marina Tsvetaeva's life straddles two very different worlds: the late-Tsarist period of her childhood and the turbulent early-Soviet period that followed. She came from a culturally aware and intellectual family – her father founded the famous Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts – and was an imaginative child who started writing poetry at the age of six. But by 27 she had lost a child to starvation and barely five years later had been forced to leave Russia, the country she dearly loved.

An outcast among the exiles

Tsvetaeva emigrated to Berlin in 1922 to rejoin her husband, Sergei Efron, who been forced to flee after the White Army's defeat by the Bolsheviks. Although she felt spiritually connected to her homeland, she was also disillusioned and alienated by the brutal new reality that the revolution had created. “It is not about politics but about the new man – inhuman, semi-machine, half-ape and half-sheep,” she wrote. The idea of the individual was paramount to the poet, and this had no place under the new regime.

Tsvetaeva found it hard to assimilate in exile too, where her rebellious and independent spirit marked her out even among others that had also left their native land: “I do not get along with the Russian immigrants, I live only in my notebooks – in my debts – and when, occasionally, my voice is heard, it speaks always the truth without calculations."

Tsvetaeva's introvert nature and unwillingness to establish connections in émigré society were not the only reasons why she and her family treated with suspicion by the Russian community in France, where the family relocated to in 1925. In fact, there were rumors that Sergei was a Soviet spy. Rumors that were absolutely true, as it happened.

During their years in Europe, Sergei would often claim that he was too sick to work. His inability to find a stable job left Marina as the sole bread winner, which put their relationship under considerable strain. However, despite their constant arguments and mutual infidelities, her loyalty towards her husband was unwavering. Efron was actually leading a double life. He was active socially and started gravitating towards Soviet ideas, eventually becoming an agent for the Soviet secret police.

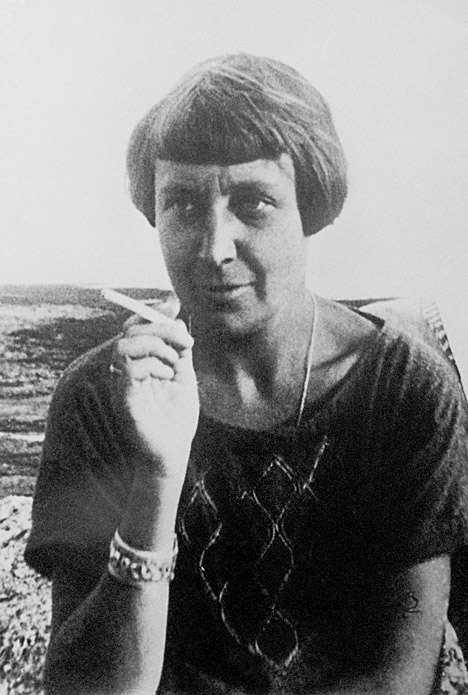

Marina Tsvetaeva with husband and children in Prague. Source: Getty Images / Fotobank

Against this backdrop Tsvetaeva’s relationship with her eldest daughter Ariadna (Alia) was reaching breaking point. Theirs had always been an intense and tempestuous relationship, with Marina showing an obsessive kind of love towards Alia, but finally in March 1937, her daughter returned to the USSR – against her mother's wishes. In June of that year, Sergei was implicated in the murder of a former NKVD agent, Ignace Reiss, and had to flee the country. Tsvetaeva's already strained family life was unraveling.

Bitter homecoming

Marina was left alone with her son Georgy, nicknamed Mur, in a very delicate situation. French publications continually turned down her work, and Russian émigré newspapers and magazines rejected her for being the wife – perhaps even the accomplice – of a traitor. Writing was her lifeblood, and yet she wrote, “I can vividly picture the day when I will no longer write verses … that day, I shall die.”

To make matters worse, Mur, who was 14 years old at this point, was desperate to reunite with his sister and father and see his homeland for the first time. In June 1939 Marina and her son boarded a ship for Leningrad. Tsvetaeva had spend 17 years outside the USSR, time that had been marked by ostracism and misery – first in Berlin, later in Prague, and finally in Paris. Now, on the way back to her native country once again, she was only journeying towards more suffering.

In July, the whole family finally reunited in Bolshevo, in a summer house for NKVD agents in the outskirts of Moscow. Unsurprisingly, in Stalin's paranoid Russia of the day, this did not herald the start of happier times. Alia was arrested for espionage, followed by Sergei a few months later: Alia had been tortured in Lubyanka until she signed a statement confessing that she and her father had been working for the French Secret Service. Months later she retracted this initial confession, but it made no difference – Alia was sentenced to eight years in labor camps, and Sergei Efron was executed by firing squad in 1941. The swift and brutal state apparatus had now taken everything from Tsvetaeva except Mur.

Crawling down a dead-end street

On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The Nazi Army advanced rapidly, and the first bombing raids in Moscow had started by July. Marina and Mur were evacuated to the town of Elabuga, where they took up residence in a creaking old country house – a stark contrast to the grand Parisian surroundings of their émigré period.

Tsvetaeva was unemployed with no financial means, and she had no idea whether her daughter and husband were dead or alive. She entered a dangerous spiral, as described by her son Mur in his journal: “Mother lives in a suicidal haze and she speaks of nothing but suicide. She does nothing but cry and speak of the humiliations she must suffer. … Mother says, let it all be lost and I will hang myself.” (Aug. 27, 1941)

The day before Mur made that entry, Tsvetaeva went to the nearby town of Chistopol, where some other evacuated writers were living. During that visit Tsvetaeva expressed her wish to receive registration and lodgings in Chistopol and had left an application to work as a scullery maid at a writers’ canteen. This was a woman desperately torn between the desire to struggle on through the hardship to support her son, and the pull of ending her almost lifelong suffering.

August 31 was a Sunday. Tsvetaeva was alone in the house; she wrote three goodbye letters. The first was addressed to whoever found her body. She asked them to take Mur to a town near Chistopol where the poet Nicolai Aseev lived. The second letter was for Aseev and his wife, pleading them to look after her son and requesting they accept a trunk containing notebooks with her poems, as well as bundles of prose writing. This fell on deaf ears, as the Aseevs failed to take care of either Mur or Tsevtaeva’s legacy. The last letter is addressed to Mur: “… I am madly in love with you … Tell Papa and Alia – if you see them – that I loved them up to the very last moment and explain to them that I ran into a dead-end street.”

When her son returned home he discovered that the worst had happened: Marina Tsvetaeva had hanged herself at the tender age of 48. She was buried on August 2 in the Elabuga cemetery, although her exact burial site is still unknown.

Although her life was one of almost unrelenting struggle, Tsvetaeva retained a belief that her poetry would echo down the generations:

"Amidst the dust of bookshops, wide dispersed

And never purchased there by anyone,

Yet similar to precious wines, my verse can wait

Its time will come."

She was absolutely right.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox