Head high in a papakha: The history of a hat that can never be removed

Krasnodar. Cossacks in the street during the All- Kuban Cossack Rada, 1990. Source: TASS / Vladimir Velengurin

For centuries, one of the distinguishing features of the Cossacks (a group of ‘free’ people who traditionally lived in semi-military communities along the southern edges of Russia) has been their uniform, and in particular the eye-catching hat they are known for wearing, the papakha.

In the Caucasus – the homeland of the papakha, also known as the astrakhan hat - it is said that “If the head is intact, a papakha should be on it.” Other popular sayings include “A papakha is worn not for warmth, but for honor” and “If you have no one to consult, consult your hat.” All Cossacks know the saying that the most important things for a Cossack are his shashka (a special kind of saber) and his papakha.

Blood feud

Custom traditionally allows the man donning a papakha to remove this special hat only in particular cases; for example, when requesting the end of a blood feud between clans. Earlier, if a man threw his papakha on the ground in the heat of an argument, this meant he was ready to fight to the death.

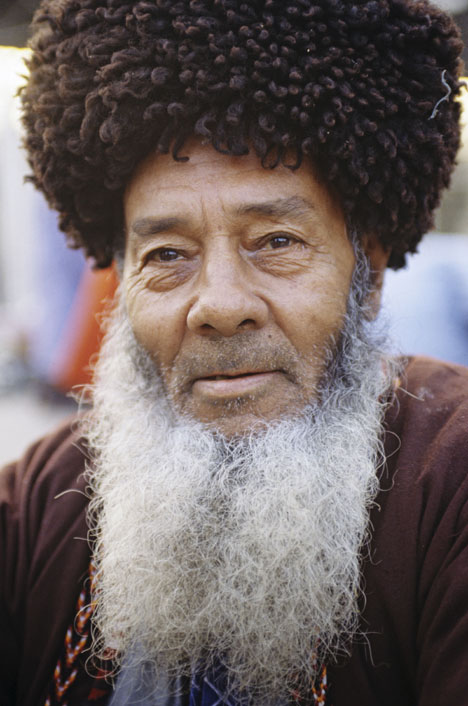

Elderly Turkmen man. Source: Vladimir Vyatkin / RIA Novosti

In Dagestan (Russia’s southernmost region, bordering Azerbaijan,) it was a tradition to use the papakha as an aid when asking a woman’s hand in marriage. If a young man wanted to woo a young lady but was afraid to do so openly, he tossed his papakha into her window. If it took a long time for the target of his affections to throw the hat back, this meant a favorable outcome for the young man. It was considered a serious offense to knock a man’s hat off his head.

Because the papakha is so tall and heavy, it prevents its wearer from being able to bow his head. It is almost as if the papakha “disciplines” its wearer by forcing him to keep his back straight.

The papakha is the most precious item in the Cossack uniform, and although many Cossacks will remove it when entering a building, they will take care to ensure it remains close by. When visiting the theater, Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov would buy two tickets – one for himself and one for his papakha.

Renowned Chechen dancer and actor Makhmud Esambayev was the only deputy in the USSR Supreme Soviet who was allowed to participate in meetings with his hat on. It is said that when he looked out on the audience before his speeches at the Soviet, Leonid Brezhnev would see Esambayev’s papakha and say, “Makhmud is here, we can begin.”

Cossack papakhi

The Cossack papakha is distinguished by the type of fur that adorns it and its height. Prior to World War I, papakhi were usually made of bear, sheep, and wolf fur, as these furs better softened saber blows. There were also parade and officer papakhi trimmed with silver braid. Cossack fighters from the Don River area, Astrakhan, Orenburg, Semirechye (in south-eastern Kazakhstan), and Siberia wore papakhi similar to a cone with short fur.

Gray was the most popular color for a papakha, though generally papakhi could be any color except for white, and during wartime black. Brightly colored papakhi were also prohibited.

A papakha with a tumak

The word papakha has Turkic origins and is literally translated as “hat.” The word entered the Russian language during the Caucasian War of the 19th century, in which the Russian Empire invaded and annexed the North Caucasus. At that time, an idiom entered the language: “to thrash the tumaki;” in other words, “to soundly thrash” someone.

A tumak is a long cuff sewn to the top of a papakha that was common among Don and Zaporozhye Cossacks back in the 16th and 17th centuries. Prior to battle, metal inserts were sewn onto the tumak to protect the neck and head from saber blows. In the heat of battle, when it came to hand-to-hand combat, Cossacks could easily fight back using their tumaki by “thrashing the tumaki” at the enemy.

The most expensive and honored papakhi are Karakul papakhi. The word karakul means ‘black lake’ and is a common place name throughout Central Asia, though as far as papakhi are concerned, the term originates from the name of an oasis on the Zeravshan River in Uzbekistan. The fur on the hat comes from a Karakul lamb, whose pelt is removed just a few days after birth. Generals’ papakhi were made exclusively from Karakul lamb pelts.

Return of the papakhi

After the 1917 revolution, restrictions were imposed on the Cossack national dress. Papakhi were replaced with the Communist Budenovka hat, although the original hats made their return in 1936. Cossacks were allowed to wear short, black papakhi.

Two stripes were sewn onto the top of the papakhi in the form of a cross – a gold one for officers and a black one for rank and file Cossacks. And of course, a red star was sewn on the front of the papakha.

The papakha became part and parcel of the Red Army’s high command uniform in 1940, and after Stalin’s death it became a popular accessory for members of the Politburo (senior Communist officials).

First published in Russian in Russkaya Semyorka.

Read more: Worth going to prison for: Getting hold of jeans in the USSR>>>

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox