Lives of the Great Patriotic War: the untold story of Soviet Jewish soldiers

Members of the Moscow Association of Jewish Veterans in front of the Moscow Central Museum of the Great Patriotic War. June, 2010. Source: The Blavatnik Archive

While the tragedy suffered by European Jewry in the period from 1933 to 1945 has been the focus of extensive study, the patriotism and sacrifice of Soviet Jews in the war against Nazi Germany remains mostly unknown.

Recognizing this important and overlooked chapter of Jewish history, industrialist and philanthropist Leonard Blavatnik, Founder and Chairman of Access Industries, launched a long-term project to record the oral testimonies of Jewish soldiers who fought in the Soviet Red Army during WWII.

Half a million Soviet Jews fought in the armed forces and partisan detachments of the Soviet Union. More than 200,000 perished on the battlefields. Between 2 and 2.5 million Jews from Soviet territories were murdered in the Holocaust, comprising half of the Soviet Union’s total Jewish population on the eve of the war.

The goal of the Blavatnik Archive is to preserve the stories of Jews in the war through the remembrances of those who fought. Since 2006, the Archive has conducted video interviews with more than 1,100 Jewish Red Army veterans in 11 countries around the world.

Moreover, thousands of archival photographs, documents, and letters have been digitized.

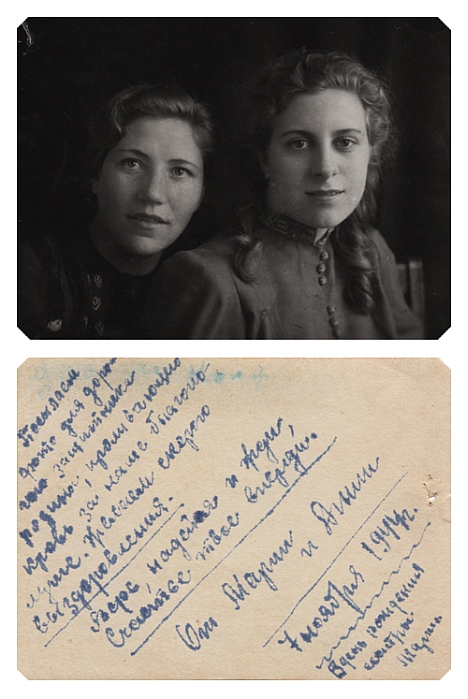

On her birthday, Maria Iosifovna Koyfman sent her brother Grigoriy a photograph, along with wishes for his fast recovery from the wounds he sustained at the front. November 1994. Source: The Blavatnik Archive

In video recordings the veterans share their individual stories; about their youth, about the humanitarian disaster that followed the Nazi invasion, about wounds and death, about friendship on the front forged by blood, about grieving the dead and longing for family.

“I am certain that the materials preserved in the Archive can help illuminate a mostly unknown chapter of Russian Jewish history,” said Blavatnik. “Tens of thousands of Jews fighting in the Red Army were awarded with orders and medals of the Soviet Union. We should always remember the heroism of all who fought in the war, and express our gratitude to the generation, which with unprecedented courage and self-sacrifice, rose to defend the future of humanity.”

The Archive, based in New York, participates in joint projects with museums and educational institutions in Russia, Canada and Israel.

Oleg Budnitskii, Head of the International Center of History and Sociology of World War II at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow has been a member of the Archive’s academic council for several years. “The Jews who, especially in the West, are often viewed exclusively as victims of the Holocaust, are presented in the Archive as soldiers fighting the Nazis, defending themselves and avenging their relatives,” Budnitskii said.

Budnitskii pointed out that it was only in the Soviet armed forces that Jews could demonstrate a massive and active resistance to Nazism. In addition, Budnitskii noted that the Archive project is unique because the subject of the Holocaust was not widely discussed in the Soviet Union.

Since all nationalities were considered equal citizens of the Soviet state, emphasizing the suffering of Jewish people during the war was not considered patriotic. “In places where mass murders of Jews took place, there were signs commemorating the death of Soviet citizens killed by the Nazis, even when they were killed only because they were Jewish,” Budnitskii said.

Archive Director Julia Chervinsky said that the project’s objective is “to preserve a picture of daily life on the front and to contribute to a better understanding of World War II. After all,” Chervinsky added, “there was not one family in the entire territory of the former Soviet Union that was not affected by the tragic events of 1941-1945.”

Some material in the Blavatnik Archive, including interviews with veterans, can be found online. The Archive has also recently published the first in a multi-volume, bilingual series about Soviet Jews in the war. It hosts exhibitions and makes its materials available to researchers upon request.

In their own words

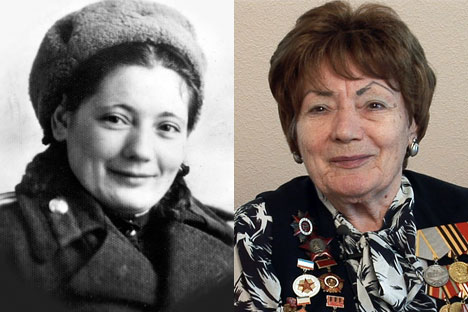

Interviewed in Tel-Aviv, Israel. 2008. Source: The Blavatnik Archive

Roman Davidovich Yagel saved his life by admitting he was a Jew to his commanding officer.

Our mission was to get through the front line and destroy the [enemy’s] division headquarters. And the Regiment Commander and his deputy were looking for volunteers again. No one raised their hand. I raised mine. After I raised mine others started raising theirs.

So 70 or 80 people gathered who said, “We are going on this mission.” On the second day the regiment commander calls me and says “You’re not going on this mission, you are a spy.”

I said, why am I a spy? He said, “you raised your hand first.” I said, yes, I raised my hand because no one else raised their hand and after me all those others raised their hands. I was first. And for that I’m a spy?

“Yes, you were captured and you were probably in captivity and you are probably going to report back to the Germans.”

I barely survived, and it’s already the second time that he’s telling me I’m a spy. I didn’t know what to do. I could tell that they were going to shoot me here. And that’s when I decided to tell him who I was. I said, Comrade Major, I want to tell you something but please don’t tell anyone else. “What is it?” “I’m a Jew. How can I be a spy? A Jew is going to go report to the Germans? What are you talking about?”

He looks at me and says “Do you know how to pray?” I said, “Yes, I know how to pray.” He said, “So say something.” I said “Shma Yisrael, Adonay Aloheynu, Adonay Echad.”

He said “Amen” and we both started crying. He was a Jew. He said to me “Everything’s OK, you are under my command, nothing’s going to happen to you.”

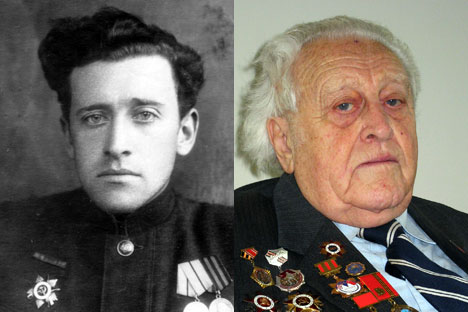

Interviewed in Moscow in 2006. Source: The Blavatnik Archive

Evgeniya Grigoryevna Aluf recalls Leningrad’s White Nights and the beginning of the war.

Leningrad was covered with barrage balloons. It was the season of “White Nights”, and we had been sitting outside on a bench, playing a guitar, singing, having fun.

Beautiful “White Nights” and suddenly war was announced. We were transported in trucks to the Leningrad Vitebsk train station, where freight trains called “teplushki” were already waiting for us. My sister and my cousin came with flowers to see me off. I wore a light blue cotton dress, thin heels and a necklace.

We thought we’d be like the girls who went to the Finnish war and then quickly returned. We thought the same thing would happen to us. Off we went. Off to the front. Where? What? We knew nothing.

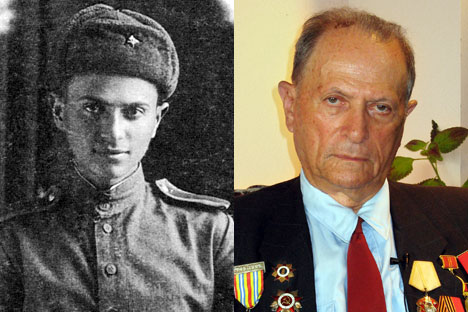

Interviewed in New York, NY. 2007. Source: The Blavatnik Archive

Simeon Grigoryevich Spiegel recalls fighting in Stalingrad.

“We slept in the basements of these houses, destroyed houses, but you could sleep in the basement. Once, my commander, Fyeodr Podisemoff, told us that in one basement the people left and there were blankets and pillows and we could spend the night there.

We slept and in the morning we discovered that there were corpses under the blankets. Those were the conditions we lived in.

Many say that it wasn’t frightening at the front. I repeat: It was frightening”.

Interviewed in New York, NY. 2007. Source: The Blavatnik Archive

Boris Iosifovich Rabiner explains the significance of WWII for the veterans in their lives today.

Probably for every front-line soldier participation in the war remained with them forever. If not a point of pride, then at least a basis of self-respect.

The fact is that there are moments in life when a man has to behave like a man should. When we were going off to war, either voluntarily, like many, or via draft, we understood that we were at war to save our country. To save our people. And this war was a war in the name truth. For the triumph of good over evil.

And so I want to repeat again and again: our participation in the war is not just our past, it’s with us forever. We don’t revisit these memories often. Usually on the eve of Victory Day or day of, when we feel our moods especially elevated.

I want to wish to our veteran friends Health, happy long years. Happiness in their children and grandchildren. To absolutely everyone, I wish for there to be such a devastating, difficult, terrifying war. For there to be peace on Earth.

More information about the Blavatnik Archive can be found on its website: Blavatnikarchive.org.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox